When the stone retaining walls and castellations of our windy campus begin to feel claustrophobic, take a sun-bleached Saturday afternoon and head out into the wilds of Eastern Connecticut. To decompress, I recently brought my scant cash and ample time to a misnamed place in Niantic, about fifteen minutes from the campus gates.

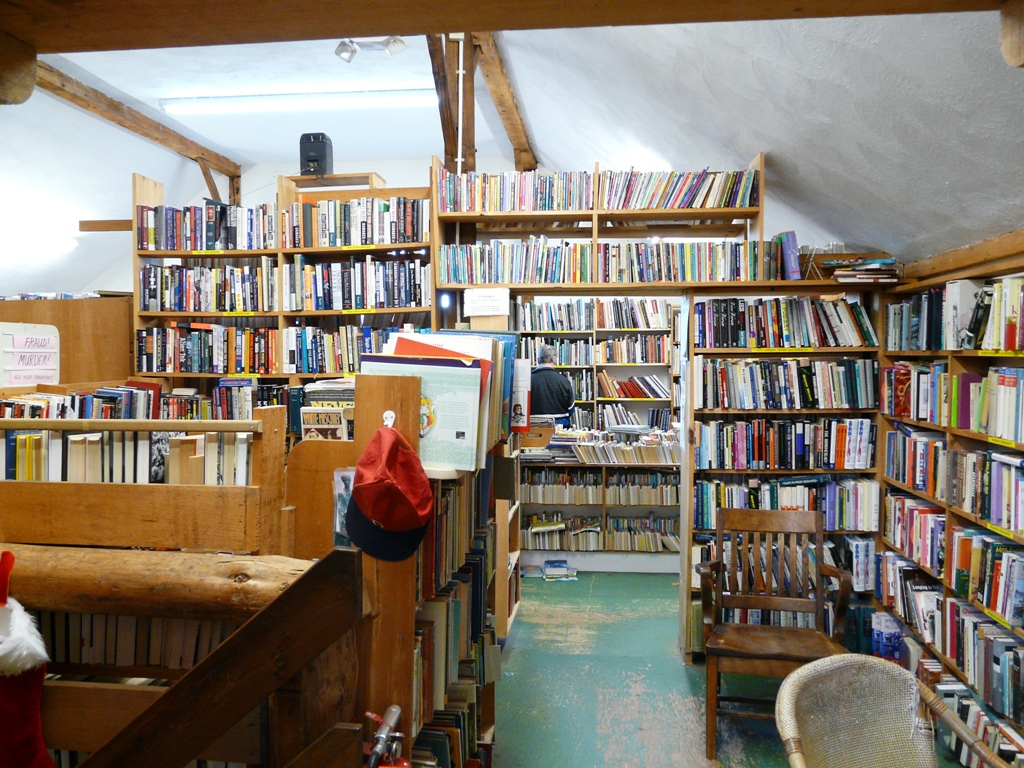

Although the compound calls itself the Book Barn, it’s actually a quiet mess of sheds, semi-permanent tents, bramble, gargoyles and goats in orbit around an old house crammed from floor to ceiling with used books. The grounds feel like the set of a fantasy film about the imagination and sense of discovery that belong to childhood – Digory Kirke’s house, Misselthwaite Manor, the Burrow. Tomes both old and modern fill basically every available space on the property, unceremoniously biding time and awaiting their inevitable discovery. There are cats; there is free coffee.

Thanks to a constant influx of discarded, marked up and occasionally unread books brought by the bagful in minivans and old Volvos to the edge of the property for cash, the Book Barn claims to have over 350,000 books on site, with about 10,000 coming in every week.

On handmade plywood shelves in the main house you’ll find ancient compilations of Connecticut vital records shelved next to children’s books and a stack labeled “Espionage.” The Spyclopedia, for the record, is $7 and has been there a for awhile.

But the Book Barn, despite all signs pointing to the opposite, is not about commerce. It’s an atmosphere of static bibliophilic escape from everything that traps us in post-modernity: there is not and cannot be an online catalog, and the wandering involved in even finding the appropriate building for the section of the author who wrote the book you’re hoping to locate, ideally in a printing that predates 1960, feels like nothing so much as the antithesis of JSTOR and Google.

Without results drawn up and organized in seconds by closest match to your keywords, any search will take you past some weatherworn object or ornament whose origins you can’t quite comprehend, and probably several animals. It’s refreshing to put discovery back into the search for writing.

The proprietary time investment and varied locales of used book hunting are underappreciated in the age of conglomerate booksellers and special orders.

I would rather have to duck slightly as I follow the tape arrows on the carpet of the labyrinthine basement stacks, trying to make out the faded gilt letters on the spine of some long-forgotten Massachusetts history than draw my fingers along the row of neatly organized, shiny paperbacks on the shelf at Barnes and Noble. I would rather have to watch my step so as not to trip on the rock, which was not removed but merely carpeted, in the corner farthest from the door than cruise past flashy displays of bestseller hardcovers and trendy teen novels on my way to the Fiction section.

Every separate location on the property has both a cute name and its own subtly distinct soundtrack. In the mystifyingly named Hades, you might expect Styx but instead listen to the New Pornographers while you marvel at the proliferation of Tom Clancy publications. The Haunted Bookstore, for thrillers, mystery, and horror, has spooky music and enough copies of The Da Vinci Code to construct a small monument to tactless prose. Some atmospheric guitar work that sounds suspiciously like post-metal will play softly as you peruse the Thoreau and John Muir collections in the Nature section.

Outside, blinking in the sun, you’ll sit on a rusted tractor as two friends play chess with giant plastic pieces. Two children compete in a clumsy game of backboard-lacking basketball. A dirty black cat inspects an inscrutable wooden structure while an assortment of solitary locals peer into bins and run their eyes across picnic tables displaying an assortment of 90s bestsellers. The man at the desk will tell you about a youngster’s recent altercation with the talking lion-shaped cookie jar. You’ll return your mug to the drawer, pay a dollar for The Adventures of Augie March and come back to the college.

As you sit down at the giant Mac display in the library, you might notice that, for once, you aren’t just switching between different glowing rectangles. An hour and a half away from the routines of campus life can give you the mental space and the non-electric, non-corporate stimulation required to reconnect the parts of your brain that open up to the unexpected. For once, your discoveries will be your own, unguided by any sort of authority or structure beyond alphabetization – and even that system is by no means in charge.

So the next time you trudge out of Harris, stare into your empty mailbox and wonder what to do with your free time, break out. Getting off campus doesn’t have to mean “going to Exchange,” and finding something to do doesn’t mean waiting for a concert or a gallery opening. Point yourself in the direction of Niantic, and bet five dollars against the prospect of discovery in the intriguing interior of a dusty, leather-bound book.