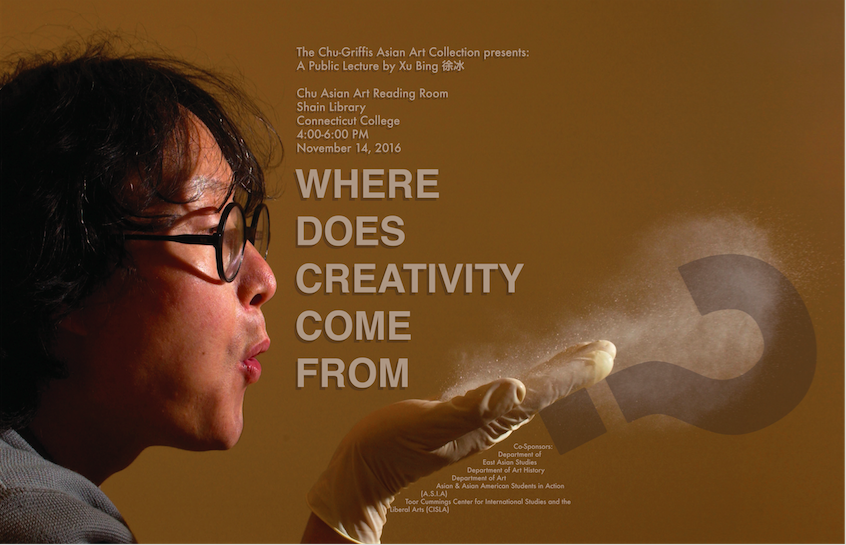

On Monday, Nov. 14 from 4-6 PM in the Chu Room as part of the upcoming “ORIGINS: Asian Art Festival,” famous contemporary Chinese artist Xu Bing will give a lecture titled “Where Does Creativity Come From?” I received permission from Conn alumna Joy Chiang ’14 to re-publish parts of her senior thesis* titled: “A New Voice for the Third Space: Xu Bing and the Redefined Chinese American Art.” Throughout her thesis, Chiang explains various parallels between the artwork that Xu Bing creates and Chinese American identity.

Introduction to Xu Bing and his works

Much of Xu Bing’s work, to put simply, intends to instigate the question, “Can People in the West learn to look beyond superficial Chinese characteristics to see what lies underneath?” Xu Bing’s trademark tactic of constructing multiple layers of meaning by juxtaposing content and form to transcend cultural boundaries is exemplified in his works that are to be subsequently studied in this chapter. Both Book from the Sky (Figure 1) and Square Word Calligraphy (figure 2) have the appearance of Chinese literati art that lead many Western viewers to believe they are appreciating “traditional” Chinese art. However, as demonstrated in these two works, there is that moment of revelation as the viewers realize that the seemingly Chinese layer of the art is a deceit and cover of the unexpected and radical content that is actually within. This culture shock element is crucial to Xu Bing’s tactic in conveying a message much larger than the blending of superficial qualities of China and the West, and to speak of universality and the ease of crossing cultural boundaries when one puts in the effort and time to understand the other. (Chiang 43)

Within the majority of his works, Xu Bing elaborates further on Silbergeld’s “third space,” of merging eastern and western attributes to create something that is neither nor, to encompass the in-between realm by “establish[ing] a distinctive space between word and image, thinking and seeing, explicit and implicit, content and context, traditional and modern, Chinese and non-Chinese, politics and aesthetics, humor and seriousness, and never just one or the other of these, and never none.” These various forms of juxtapositions in his art are one of the fundamental points in distinguishing Xu Bing apart from the rest of the archetypes of artists, because those particular elements speak to people who may feel familiar and connected to how his artworks are composed. The reflection of how an external, physical appearance that may not necessarily mirror their true content may be familiar to the identities of those who feel as though they are constantly judged by their ethnicity within the United States. For Chinese American audiences it may spark a connection to their own ethnic and cultural compositions, as Xu Bing’s art brings to attention the question of how just because the exterior physicality looks Chinese, does it necessarily mean that it can’t belong or wholly be accepted as American? (Chiang 43-44)

Figure 1 Xu Bing, Book from the Sky, 1987-1991, installation with scrolls, books, and woodblock prints.

Book from the Sky

Book from the Sky (Figure 1) is exemplary in how, like Ghost Pounding the Wall, it has evolved in meaning and significance with the progression of time and space of its exhibited context. The work was first created while Xu was still in China, and at that time it served as a cleansing of the mind from the chaos that ensued after the Cultural Revolution. After years of restriction on what books and limited information people had access to under the cultural reforms of Mao, when these bans were lifted the artist noted that “I read so much and participated in so many conversations on culture that my mind was in a constant state of chaos. My psyche had been clogged with all sorts of random things. I felt as if I had lost something. I felt the discomfort of a person suffering from starvation who had just gored himself. It was at that point that I considered creating a book of my own that might mirror my feelings.” The installation of numerous books and scrolls that carried thousands of fake characters was his response to the metaphorical gorging that he had suffered at the end of the Cultural Revolution, and its utilizing of “the sincere and formal grandeur” that comes out of “China’s high and weighty cultural tradition” was Xu’s method to produce a joke about the cultural confusion that China was caught up in the twentieth century. When the time and space of its exhibition changed to the multicultural America, the significance the work carried also developed to encompass more. In just the physical form of Book from the Sky alone, the meaning has widened to resonate with the characteristics of “third space” cultures. The way that the components and strokes that make up the nonsensical characters in the installation are assembled in an unconventional way – in which the physical images, the “characters,” remain, but the true content and meaning typically associated with the seemingly Chinese characters are lost was considered a mocking of this monument to Chinese national identity. (Chiang 46)

Book from the Sky and Chinese American identity

For many Chinese Americans who feel that their identity is not fully of one culture or the other, who may consider themselves as Americans but are not accepted fully as one, and that their identity is also assembled in an unconventional way, Xu’s Book from the Sky may strike a familiar chord. For them, they might find themselves identifying with the installation, because it also speaks of a new identity composed of Chinese and Western cultures and assembled with references to both Chinese and recent traditions that result in something that retains the physical appearance of the Chinese, but the Chinese core of the person is lost or diminished. Interestingly, Book from the Sky also evokes an emotion that is commonly affiliated with Chinese Americans. Xu’s thousands of meaningless characters create a maddening sense that affects the Chinese literate the same way that one feels frustration in not being able to comprehend or read what they expect to. Especially to the Chinese Americans either born within the United States and had little or no connection to the Chinese language, or those who came over at a young age before the language integrated into their personhood, this frustration is particularly immense. Many of these people grow up with the expectations to read Chinese based on their racial background and physical appearance, but the fact that most are not very literate in Chinese due to their background of being brought up largely in American suburban or cities are irritated whenever they are asked to read something they can’t or know little of. Book from the Sky resurfaces that aggravating sentiment, and even when one is aware that the installation is illegible it is still bothersome to behold and difficult to suppress that feeling of frustration and irritation. (Chiang 46-47)

Square Word Calligraphy and Chinese American identity

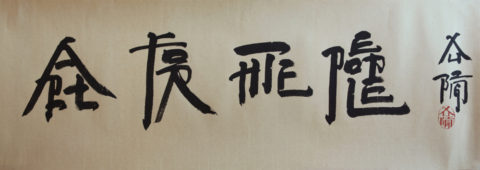

Similar interpretations can be said for his work Square Word Calligraphy (Figure 2), utilizing the English Square Word that Xu created after his move to the United States as part of his response to experiencing living between cultures. As an artist, Xu attempts at an ethnic identity redefinition in his Square Word Calligraphy through the approach of “cultural camouflage,” a concept he introduces to mask and disguise the cultural origins of his work to avoid the various pre-established and imposed meanings and expectations that are associated with a certain ethnicity’s art. This strategy is exemplified in this work through the restructuring of English words into a square format to resemble Chinese characters, so as to confuse cultural origins and ease off of the theme of a single nationality.

The English Square Words he created “resemble its subject in what it is, but inside it, it does not truly represent its subject”; in other words these symbols that are seemingly Chinese do not actually embody the culture that its appearance signifies. A concept, that once again, resonates with the construction of a Chinese American identity. With art such as this, Xu stated that he takes interest in tackling the issues that may be difficult to explain to those outside the “third space”, and for Chinese Americans it is imperative that he does so, because he is able to address and spread widely what they cannot, it being the difficulty of explaining what it means to have the appearance of a Chinese but not the cultural embodiment or the fidelity to China that is expected of them from outsiders. (Chiang 47-48)

The issue of defining what it means to be Chinese American is not as black and white as some people may think, just as how Chinese artists no longer consist of just those that are born in Mainland China and produce artworks that exhibit the expected cultural elements and themes. Xu Bing’s rationale in creating artworks like Square Word Calligraphy is to communicate to others what it’s like to live between cultures and experience that sense of not belonging to one specific nationality or the other. With his trademark tactic of introducing the culture shock element in his art, he instigates people to think beyond what they have become accustomed and told of about a certain country and everything that comes from it, whether it’s the people, culture, language, or art. These ethnic and cultural identity issues are certainly difficult to straightforwardly define, and while it may be easier to just follow the trend of utilizing the already established connotations and stereotypes about a certain culture and its people, Xu’s art is meant to jolt that assumption and encourage people to think beyond the boundaries established by a Western construct. Essentially, he wants to spread the message that an artwork made by someone of Chinese descent isn’t always meant to translate the politics of China, just as Chinese Americans are more than the preconceived and long-established stereotypes that have been their haunting since late nineteenth century. (Chiang 48)

Traveling to Wonderland

Traveling to the Wonderland (Figure 3) is one of Xu Bing’s more recent art installations that proves how the artist continues to uphold his philosophy and purpose even after more than a decade of being an internationally renowned artist. The piece was installed at the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum in London utilizing the John Madejski Garden in 2013, to create the fabled utopian landscape inspired by the classic Chinese tale Tao Hua Yuan (The Peach Blossom Spring), a myth of an utopian village hidden deep in the mountains of old China. Inspired by the mythical fable, as well as drawing from elements of Chinese landscape scrolls, Xu Bing created a dreamlike, layered mountain and waterscape with the arrangement of stones he collected from eight different regions in China. (Chiang 49)

In Traveling to the Wonderland, he was inspired by the Chinese folktale and classic landscapes to relate the message that he believes is crucial for all people to understand…[the message is that] it’s in human nature to often look elsewhere for a place that has an already constructed peace and idealistic society rather than looking within ourselves and our own nations for the peace and quiet that we want. The installation is set up so that the ideal location for viewing is from the center, and when one stands there it “will feel like a person wandering inside a real landscape.” In reality, however, visitors are denied the access to stand in the middle and can only look forlornly from afar on the outskirts, looking into where they want to be standing and where it’s rumored the picturesque utopian society lies. Also, because visitors are denied of the prime location of being in the center of the installation, they have a full and clear view of the “behind the scene” electronics and technologies that make the dreamlike landscape possible. In fact, there’s no effort to hide or disguise these wires, motors, and lights that power the installation, making visitors disgruntled that the modern technologies reveal “something about the fragility of the idea of utopia.”

“the reality of the ideal Chinese landscape is actually made up of western technologies and electronics…”

Like Book from the Sky, this installation emphasized the fakeness of something that seemed to be real at first. It played with people’s expectations and delivered something completely different that in the end didn’t convey anything about China, but rather it taught the audience about themselves and the ideas that they have become accustomed to in thinking about the art of China. And like Square Word Calligraphy, it conveyed that what is seemingly exotic is really just a construct in our own mind and, in this case the reality of the ideal Chinese landscape is actually made up of western technologies and electronics. And in much similar ways, this ties to how the foreignness and “otherness” of Chinese Americans are really just within the imagination of mainstream America. Once that is accepted, perhaps it will be easier for others to grasp the reality of just how familiar and “American” they truly are. Once again, Xu Bing accomplished the task of carrying out the message that the “chineseness” of a person’s appearance, their “exotic” façade, is but an illusion.

Artist Xu Bing as “a new voice for Chinese Americans”

Xu Bing is a new voice for the Chinese Americans because he is “sincere in his belief that art should serve a social purpose and should not be confined to be understood by a rarefied art world elite,”and his motto of “art for the people” has existed since early on in his artistic career, as exemplified by many of his artworks’ ability to speak to a large and universal group rather than culture or education of specific crowds. As an international Chinese artist, Xu has been able to create art that transcends cultural labels to speak both universally as well as culture-specifically, from tackling the experiences and issues of Chinese Americans in the United States to speaking of the universal need for crossing cultural barriers to gain better understanding of one another. In regards to how far his works spread, the artists stated, “I hope my work will reach the broadest spectrum of people possible, everybody from the art expert to the average person. I don’t feel my work has a limited audience at all. I think that if people have any feeling at all they can appreciate my work.”

Xu Bing’s art as one representation of Chinese american experience

While some may consider his use of traditional Chinese art elements as self-orientalizing and feeding what western audiences and curators expect to see in contemporary Chinese art, in actuality, for Xu the concept, formats, and medium of “traditional culture” isn’t as important as a piece of artwork’s potential for instigating and engaging in global dialogue. Regardless of what constitutes his art, it doesn’t change his desire is to speak to a larger, global community by transcending his local context, whether that is his Chinese cultural background or his international and intercultural context from when he moved to the U.S. in 1990 His intention to spread his art to a wide spectrum and reach out to people makes him a most successful representation for Chinese Americans, because if his art has the capabilities to voice the struggles of Chinese Americans then it is important to spread to as wide of an audience as possible. With his obsession with language and cross-cultural communication, Xu Bing has truly created art that not only introduces people to “a realm previously considered too obscure …to bear trespassing by the uninitiated,” but also encouraged these viewers to consider what it takes to step across cultural barriers to gain better understanding of a familiar culture previously thought too foreign. (Chiang 50)

*For Chiang’s full thesis with citations, visit Connecticut College Digital Commons