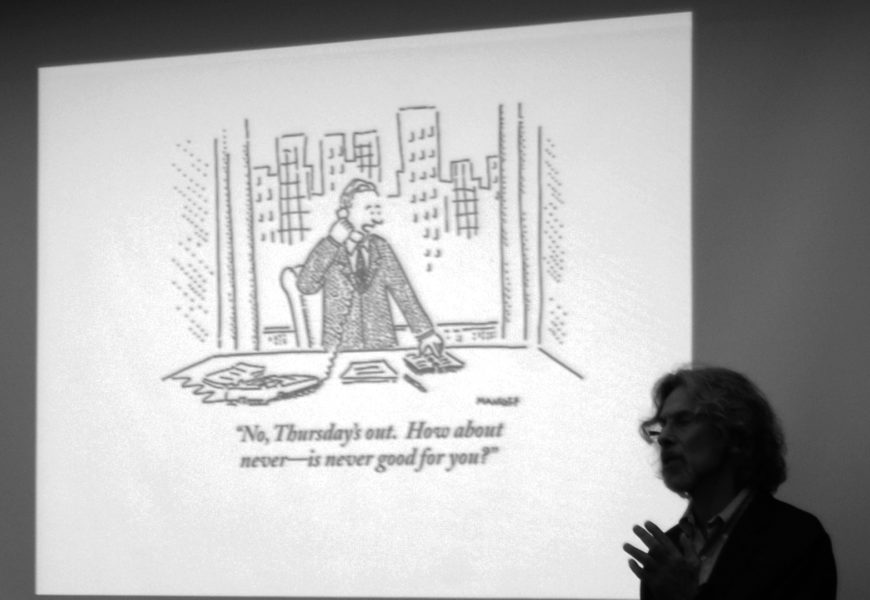

Robert Mankoff, cartoon editor for The New Yorker and author of over nine hundred cartoons, is not a cartoonist who draws naked, but he is the author of a book titled The Naked Cartoonist: A Way to Enhance Your Creativity.

Last Thursday, Mankoff visited the College to give a lecture titled “Comedy, Tragedy, Religion and Me.”

Organized by Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Sharon Portnoff, the lecture was sponsored by ‘The Saul Reinfeld Memorial Lecture in Judaic Studies,’ which brings a distinguished speaker to campus to speak in areas of Jewish interest every year.

“I selected Robert Mankoff to speak this year because of his expertise on the role of humor in American business, politics and life. He has recently been speaking at various venues about the role of humor in Jewish life,” said Portnoff.

Mankoff began the lecture by debunking the sign in the Chu room prohibiting cell phones, “I’m from New York — we’re busy people!” His cell phone did indeed ring in the middle of the lecture.

As cartoon editor of The New Yorker, Mankoff reviews over 1,000 cartoons per week, claiming that the immense number of cartoons he rejects can sour his personality. An ironic twist, Mankoff said his own cartoons were rejected from The New Yorker for two years straight before he finally was accepted.

“People ask me how I come up with cartoons, and the short answer is: I think about it,” Mankoff said of his creative process.

Aside from discussing his role as cartoon editor, Mankoff’s lecture centered around humor in general, not necessarily specific to cartoon, though they were frequently used as examples throughout the presentation.

Historically, the concept of “sense of humor” did not develop until the 1850s. People who laughed during that time were considered to be either making fun of people, or crazy.

Mankoff kept the crowd of roughly sixty audience members laughing throughout the talk as he discussed three humor theories: superiority (for example, America’s Funniest Home Videos), relief (bloopers) and incongruity (humor in which things don’t exactly match up, like Monty Python).

Towards the end of the talk, Mankoff integrated the idea of religious humor, particularly in regards to anti-Semitic jokes that were published in The New Yorker in the 1920s.

“Jewish humor,” he claimed, “makes fun of itself.”

In the case of cartoons that associate with religion and other touchy subjects, Mankoff said, “Anything you really care about can’t be funny at all,” because “we cannot both laugh and feel.”

He explained that when laughing at a joke, the audience must be somewhat removed from the situation in order to find it funny. Usually, he said, “cartoons provide distance [from sensitive subjects] because they’re not real things.”

However, Mankoff did acknowledge that cartoons have the power to emotionally damage those exhibited in the drawings; however, he concluded that their offense comes from deeper issues, not just an immediate reaction to a drawing in a magazine.

Mankoff said, “Humor is about freedom, especially the freedom to offend.”

Photo by Kelsey Cohen.