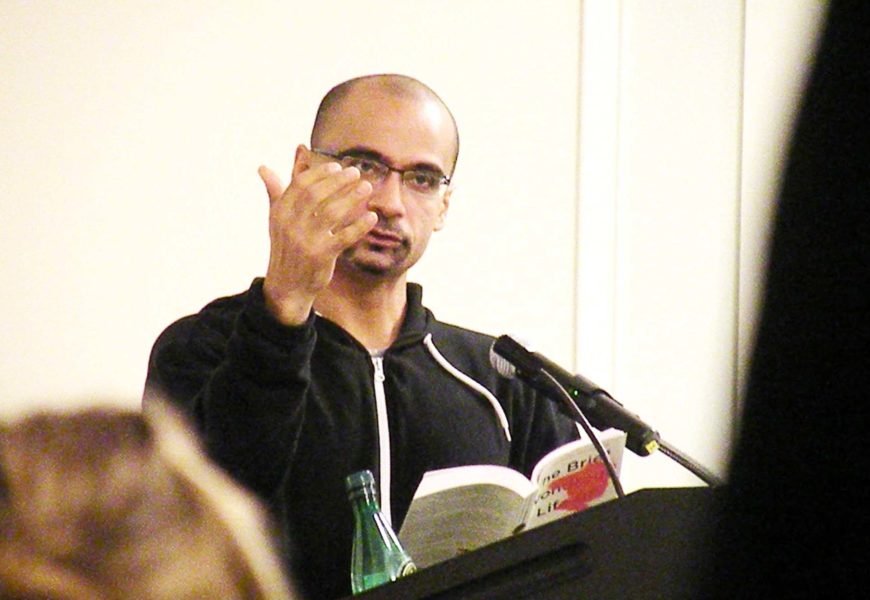

Junot Díaz. Photo courtesy of Karam Sethi.

Sometime between 7:25 and 7:35 on Wednesday evening, Blaustein’s Ernst Common Room went from crowded to packed.

Weaving his way through the crowd was an unassuming man in glasses and a green plaid jacket with glasses and a head of extremely short hair – buzzed but not kept up. He stood by the windows until English professor Janet Gezari finished her introduction, and then approached the podium under a shower of applause, which he cut off.

“For me, you never have to clap,” he said.

Junot Diaz, author of 2008’s winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, is a successful and critically acclaimed writer, the groundbreaker mostly responsible for establishing Dominican-American fiction, and a man with little regard for the traditional trappings of success.

When asked about winning a Pulitzer, he responded with a nonchalant shrug, and said that it was just a tiny pyramid of crystal for which he had no use.

He’d given it to his mother.

Part of a self-described “military family,” he described his stance on “accomplishments” as more or less disinterested, because of his parents’ attitude toward him and his sister.

As Diaz put it, “one of us could have walked across water and my mother would have said ‘sit the f— down’.”

A modest eye turned towards his widespread respect seemed to serve Diaz’s approach to his own work well.

He was gracious and eager to converse with the long line of students, professors and members of the New London community who waited afterward the talk for an autograph and a handshake.

His near-indifference to people’s high regard for his written work, however, belies a dedication and love of his craft.

In three readings from his recent novel, Diaz was clear and articulate, but not theatrical, allowing the meticulously groomed language and narrative power to speak for itself.

The audience was engaged, with several lines eliciting hearty laughter and others adjourning to poignant and complete silence.

In the question-and-answer session which followed his reading he was impassioned and highly complementary of his peers, naming four contemporaries and Harlan Ellison as his favorite authors.

Every question about his own novel prompted Diaz to expound at length and with stunning command over the thought and craft behind the writing.

The questions that most seemed to interest him dealt with the kinds of language within his novel, which range from the sharp-edged and finely honed diction of a habitual reader and lifelong student to the no-big-deal use of profanity that he also brought to his talk, and from Spanish-language slang to frequent, obscure science-fiction references.

Most of his answers had larger implications for his approach to culture and writing in general.

Asked whether he intended to make parts of his novel unintelligible to non-Spanish-speaking readers, he laughed.

“The book’s got more nerdish than Spanish, but people only get pissed off about the Spanish,” he said, before shrugging off the politics of his response and moving on to a recommendation for those readers he’d left behind in slang. “The parts that you don’t understand, a novel invites to you find someone who does.”

The thread of community-based reading extended throughout Diaz’s entire talk, and represented his commitment to encouraging people to live with each other.

His novel’s eponymous character’s life is “wondrous,” he said, not because the character was rich or adventurous, but because “he left more love in the world than he took out.”

If love is the quality that makes a life wondrous, then Diaz’s life as a writer must be just as wondrous as the character in his book.

All the obvious love for his work that collected in Blaustein the writer appeared to take in stride with polite and humble gratitude.

All the love he showed for his influences and his subject seemed to overflow in his endless stream of observations and statements that kept pen-hands skittering across paper throughout the room and eyes and ears locked squarely on the man behind the podium.