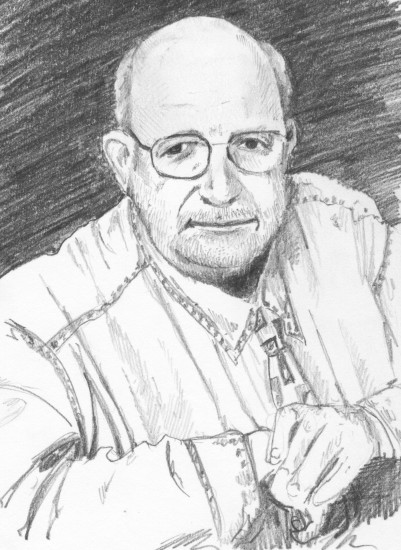

Art Kreiger, Sylvia Pasternack Marx Professor of Music, a fellow in the Ammerman Center for Arts and Technology and the Cummings Electronic and Digital Sound Studio, is also a prolific composer who specializes in electronic music. At Connecticut College, he teaches Tonal Theory, Electroacoustic Music and Music Through Time and Society.

Art Kreiger, Sylvia Pasternack Marx Professor of Music, a fellow in the Ammerman Center for Arts and Technology and the Cummings Electronic and Digital Sound Studio, is also a prolific composer who specializes in electronic music. At Connecticut College, he teaches Tonal Theory, Electroacoustic Music and Music Through Time and Society.

“We’re a small department,” he said on a rainy Friday afternoon in his office. “They move me around a lot.”

Kreiger was born in New Haven, Connecticut. He grew up in Milford and attended the University of Connecticut.

“I majored in English as an undergraduate. I took music theory courses there concurrently,” Kreiger said. “I truly like both areas of study, but when I got out of college, I preferred writing music to writing. I have no regrets about that.”

Krieger’s musical career started long before graduation. “I was a drummer in a number of rock bands, but my heart wasn’t in it, and I wanted something more.”

After graduating from the University of Connecticut, he earned his Doctorate of Musical Arts at Columbia University. “It was there that I became acquainted with electronic composition, I thrived there and loved it,” Kreiger said.

In his spare time, Kreiger listens mainly to the canon of Western Classical music. He’s never been a big fan of rock and roll. “My heart isn’t with the mass of synthesizers heard today,” Kreiger said. “Electronic music is much more timbrely diverse-it’s interesting to me.”

Kreiger started as a part-time teacher at Conn in 1999, and became a full-time professor in 2004. Occasionally, his music can be heard sweeping through Cummings from his office door, which is usually kept ajar. In his office, two major objects attract the eye: the piano and the elaborate sound system that decorates his desk. Currently, he is hard at work on a composition for the Orchestra of the League of Composers, the oldest musical organization devoted to contemporary music. “It occupies most of my time at this point, frankly,” he said. “All of my creative time, anyway.”

The piece is called “Sound Merger.” It is for a chamber orchestra and it will feature electronic and classical music played side by side. He launches into an explanation of the complex cross-fading process that is important to the piece.

“It’s been my style to do this kind of thing,” he said. “It’s about half-done. Gotta hustle, have a deadline in April.” The music is written down on large, rectangular sheets of yellowed parchment. “I was trained to write on paper,” he says. “I’ve gotta write it down to tell the conductor, so he can coordinate the electronic sound with the players.”

He plays the electronic portion of the piece on the loudspeakers in his room. It is loud, dissonant and at times even startling. As each section ends, he quickly turns another page of parchment to keep up. Chords reach the height of their crescendo and cause the desk to vibrate in response. This electronic sound, as well as the absence of sound, helps to create a dim, dense void.

“This is very different from the music world [at Columbia University], but it’s all a digital attempt to replicate the classical techniques found in an analog studio,” said Kreiger.

It does not appear to be, in any sense of the word, easy. On the computer screen, multiple tracks lie scattered throughout the screen in horizontal bars in complex sequences. “The learning curve from analog to digital is steep,” he says. “I’m glad we have an engineer here, Jim McNeish, because most of my questions are, at this point in time, technical. That doesn’t mean I don’t struggle with aesthetics. I do every step of the way. But that’s my own thing.” •