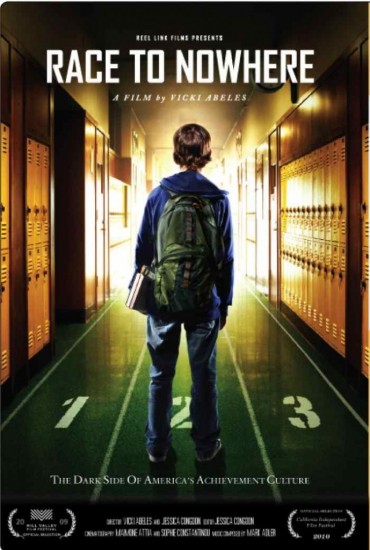

Race to Nowhere theatrical poster. Image from web.

Is our educational system in trouble? Yes. It’s hardly a question. I was in the public high school system as recently as a few months ago, and if you asked me back then whether I thought something was up, I would’ve given a very snappy “yeah” before storming off to go stress somewhere in solitude. Because the truth is that our educational system (our public one, anyway) is a mess right now. And after attending a screening of Race to Nowhere, a documentary on the negative effects of over-intense schooling on our nation’s youth, along with an audience of teachers, administrators and students alike, I’d be surprised to hear anyone say otherwise.

But what specifically is the problem with our education system? Number-worshippers might say that the problem is test scores. They’re too low (compared to other countries) and since the education process IS apparently a worldwide competition complete with medals and ribbons for the best horses (sorry, students), it’s up to us and us alone to turn off the computer, put the McDouble down and start pushing ourselves harder. Right? Wrong. In fact, it’s this line of thinking that Race to Nowhere attacks: the film suggests that the problem isn’t that students aren’t trying hard enough. It’s that they’re trying WAY too hard.

Through interviews with students of different ages, parents and public school teachers, Race to Nowhere, directed by Vicki Abeles (a mother with two children) looks at the lives of overachieving students and how their packed schedules have a negative impact on their physical and mental health. The consequences of such a schedule are emphasized mainly by roughly thirty minutes worth of close-up shots of students gazing apathetically out of windows or into walls. Overdramatic? Not really, and that’s what is kind of messed up.

Interviews with overworked students revealed a girl in junior high who developed stress ulcers that were so bad she had to be hospitalized. One girl in high school studied so often she found little time to do normal teenage things like hang out with friends, go to the movies or even eat food. She developed anorexia and spent time in an institution. What was the cause of these ailments? These students had too much schoolwork.

But it’s not just the schoolwork; it’s the extracurricular activities. Soccer practice, gymnastics, piano lessons, volunteer work, etc. When you pile six hours of homework a night onto who-knows-how-many hours of extracurricular activities, it’s a wonder anything gets done. The real driving factor behind all the stress, however, lies in the competitive mentality of a school system that has become obsessed with number-based achievement. While the age-old adage, “If I study real hard in school, I’ll live a better life when I’m older,” is often a good motivator; it’s the end goal that needs analyzing.

What is a better life? Is it living in a nice house? Why is the dream of buying a house so prevalent anyway? Plenty of miserable people have excellent houses. But when I got a bad grade in school, which according to the students (and me in high school) was anything below an A, I could see my future house (and happiness) disappearing, and irreversible, grinding poverty taking its place. Fear of poverty is a factor, but there are other factors, too. Many of the students felt pressured primarily by their parents to do “better” and take on more responsibilities. Not all parents are like this, however, and some of the students drove themselves to the verge of a breakdown.

So whose fault is it then? Is it the teachers’? The fact that so many local teachers showed up to the screening of the movie puts that idea out of the picture, in my opinion. Also, many of the teachers interviewed in the documentary seemed to know exactly what the problems were, as well as their causes. There is so little teachers can do when SAT scores essentially define a student’s worth, and the time for college applications is characterized by kids too busy studying to argue or question anything.

To be fair, the movie does end on a positive note. Solutions are proposed, some good and some radical. For example, one woman who helped contribute to the movie was Sara Bennett, creator of the now-defunct blog Stop Homework. You can guess what her agenda is. This idea of ceasing all homework was highly disputed in the discussion that took place following the end of the film. Michael Freeman, First Vice President Director of the Stonington Education Association, agreed with certain aspects of the film, but seemed to think that the idea of removing all homework would be counter-productive to the student’s education, not to mention unfair to teachers who rely, understandably enough, on homework to fit the proper amount of work into a course.

Doug Lyons, Director of the Connecticut Association of Independent Schools, expressed strong discontent with standardized tests and the fact that they often prove nothing about the intellectual capacity of a student. Rather, they focus narrowly on math and reading and all but forsake art and other subjects. He also talked about how the skills required to be “successful” in the twenty-first century have changed. Things like teamwork, cooperation and verbal skills are the traits employers currently value. He mentioned a new kind of test he had seen; a team of students was given a problem, materials, and a few hours to solve it. He said he thought it was, “the future” of education.

I’m inclined to agree. The education system hasn’t changed much in the past hundred years. It is, like much else, stagnating. As the world progresses and develops, the educational system has to adapt to fit its students’ needs. Otherwise, what’s the point of getting an education at all? •

Good review, was the screening you went to on campus? If not, we should have one soon.