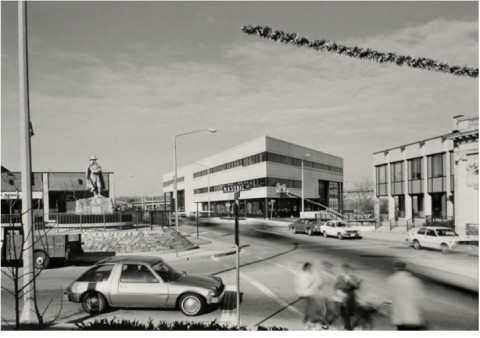

A photo of Eugene O’Neill Drive and Masonic Street approximately 30 years ago by Ted Hendrickson. Photo from Hendrickson's website (click here).

For those of us who only occasionally spend occasional time in New London, everyday sights can easily slip by, unnoticed, behind a stimulus shield built up by full gas tanks and their attendant trips to bigger, flashier cities. For residents, however, every street corner is a record of a public history, as inscrutable to the novice eye as cuneiform on a clay tablet.

Conn Associate Professor of Art Ted Hendrickson, a lifelong resident of New London who has been with the College since 1989, unveiled a new collection of photographs last Wednesday at the College’s downtown Provenance Center that aims to make that history relatable, contrasting landscapes from 1980 to 2010 in order to tell the story of a city in search of its identity.

“Photographs are like poems,” said Hendrickson. “You take the mundane, and select carefully to turn the simple into the profound.”

The collection, which features both color and black and white photographs of local spaces, relied on context and contrast to tell its stories. Two triptychs of the same corner on the Fort Trumbull peninsula, for example, revealed the desolate blankness of the post-Pfizer landscape. The first, from 1999, shows a brick bakery and a few residences; the second, from 2009, merely depicts weeds on a small hill.In keeping with his view of photography as a document of perspective, he was clear to even the desolation is an impression.

In contrast to the archival shots in the Black Line Gallery of the Provenance Center, Hendrickson’s New London is indeed empty — where photographs of the city in its heyday show throngs of sailors and townies working their way down State Street, the new collection’s sole visible person is a Pfizer worker tearing recyclable materials off a house acquired via the pharmaceutical company’s controversial eminent domain acquisitions.

“When I returned [after college], I saw emptiness and disappointment,” he said. “People were leaving; businesses were shutting down.”

Hendrickson’s bleak take on the town has often netted some criticism for its lonely editorializing.

“People say, ‘the pictures are nice, but it looks like a neutron bomb went off,’” he said. “But it’s not like I’m going in and erasing the people,” he added.

Hendrickson also theorized that his semi-conscious attempt to leave his frames empty of people was ideological, and defended his unpopulated shots as an attempt to invite the viewer in: “If it’s empty, you have to put yourself there.”

But Hendrickson also seemed to think of himself as less interpretive than honest. As the de facto historian for a town with a lot to think about, he said that the emptiness in his photographs was more representative than interpretive — his collection is the end result of years of casual photography rather than a completed archival project.

“I’m going to be taking photographs as long as I can still drag my sorry ass around town with a camera,” he said. “I try to keep my finger on the pulse by reading the papers and listening to people talk.”

As for insight into where the city is headed, Hendrickson was less forthcoming.

“There’s a recent optimism here, fueled by the arts,” he offered, “but I’m not so smart nor so proud as to think I have any answers.”