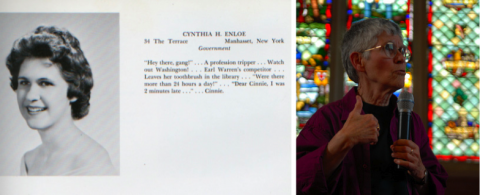

Ms. Enloe, 1960 and today. Yearbook photo from Koine.

“That is okay. That is absolutely wonderful,” she says with a look full of conviction, and I realize that Cynthia Enloe has pierced right through my inner thoughts and feelings. Although I embrace feminism with assertiveness, a tinge of insecurity remains when I meet someone outspoken about issues so often skeptically received. “You don’t need to sound apologetic when you say that you are feminist,” she continues, and in a reassuring gesture, gives me a smile. We are at yet another Wine and Cheese reception that will become more frequent as the semester draws to an end, sporadic but certain reminders of a hard-to-face fact for the senior class: we are graduating. But this time around, all my attention is set on the woman who has contributed to feminist literature in an immeasurable way, and who, to our fortune, will be delivering this year’s Commencement keynote speech.

When I first spotted Cynthia Enloe ’60, I felt strangely relieved. Finally, I saw the face of the scholar whose activism I’ve read so much about in Professor Tristan Borer’s seminar “Women and World Politics.” Perhaps inadvertently, I have always pictured Enloe as a giant. Blame it on my inability to wrap my head around metaphors like “you are as big as the size of your ideas.” Right. But if this adage were true, and the magnitude of our ideas were proportional to our physical heights, then she would be much bigger than her actual size: something resembling an intellectual she-Hulk.

“Political theory used to terrify me,” she tells the student who asked her about her most challenging course as a student at Connecticut College. I silently giggle at the irony; I find it amusing that the very woman who’s placed her finger on the flaws and contradictions of conventional understandings of economics, globalization, militarization and plenty of other subjects was once scared of them. But I presume that this is the reason she majored in government: to overcome the troubles of realism and challenge it at its core. And there is no doubt she has raised an intellectual battle by turning everything we learn in Politics 101 on its head. Her weapon is an unfaltering “curiosity” that she praises as a remnant of her education at Conn. “‘What if,’” she says, “can be a radical question.”

Enloe believes that there is no such thing as “collateral damage” in a war, only women and children who are being misplaced, wounded and killed amidst the theatrical battle of men with big guns. There is no “cheap labor,” she denounces, but only labor that has been made cheap. And she does not go about rationalizing prostitution like many do. She questions notions of this practice that make it appear as commonplace defiantly. “Prostitution seems routine. Rape can be shocking,” she once wrote in her book Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives. “Around a military camp, prostitutes connote tradition, not rupture; leisure, not horror; ordinariness, not mayhem. To many, militarized prostitution thus becomes unnewsworthy.”

Now she is addressing the whole room: “Last year I came to…” she pauses, whispers, “my fiftieth reunion.” I wonder if fifty years from now, I will be able to look in retrospect without fearing disappointment. I wish I could fast forward time five decades and see if I will still find anything interesting to talk about, if I will not decide to withdraw from society and hide in a cave because I rather not bear with the fact that my generation, actually, has not changed the world.

“There was no nostalgia in the conversations I had with my classmates,” Enloe says of the reunion, and I must say I was a bit surprised by her comment. She carries on: “We didn’t talk about the good old days and how much we missed them. Instead, we talked about the war in Iraq, issues in the media and so on, and all because we came out of here and share the same kind of curiosity.”

Enloe is interested in finding links where there appear to be none. She is the best at making those connections that make us all responsible for each other. “I could not go about living in this world without thinking about it all the time after Conn,” she tells me when I ask her about the impact of college on her life. Her statement is proof of what the books she has written convey, which is an acute awareness of the way our decisions have a reverberating effect. In her writings, it’s clear that she will not let any ideas that guide our lives and shape institutions go unchecked. And she does so by humanizing the theories that dominate political, social and economic discourse. At the end side of any policy, there will be a human, and let us not ever forget that.

“To be a feminist is to take women’s lives seriously,” Enloe expresses with a clarity that I envy. I still shamefully struggle to counter the prejudices that ill-informed people have about feminism. “It does not mean that if you are feminist, you will consider all women to be angels. But you will certainly make much better sense of the world if you ask yourself where we fall in the bigger scheme of things.”

I look at her and I wonder what she will tell us on that day before we leave the comfort of college, when all our worries and hopes will be focused on finding a place in the market jungle. “Certainly, I will bring up the fact that you are, as I was, very privileged to be here, at this great institution.” Indeed, I have been immensely lucky to be exposed to the works of brilliant minds as hers, which have totally redefined my perceptions of everything. “But you may not forget that with more privileges also comes more responsibility,” she tells me. A chill of fright travels down my spine. Will any of the four hundred of us who are graduating this year be able to honor our education at Conn in the admirable way that she has? Can we be responsible? Fifty years ahead, and we perhaps will know. •

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Thumbs Up Club, Tiffany Chen. Tiffany Chen said: Who is Cynthia Enloe '60? Graduation speaker, political theorist and feminist … http://tinyurl.com/4bf583a […]