The first question was what shoes would look best with my black dress. The second question was did I feel comfortable going to an event hosted by one of the world’s worst dictators. Had I really considered the reality of sitting to listen to a man speak who denies the Holocaust, murders homosexuals, oppresses women and wants to “wipe Israel off the map”?

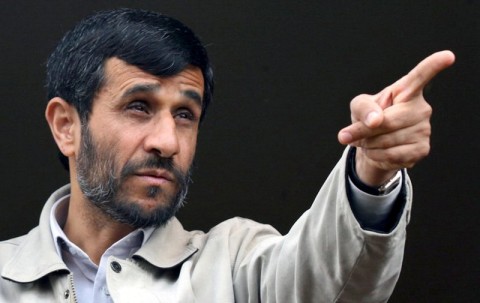

I all too quickly replied “yes” to a CISLA email asking who would like to attend a dinner and dialogue with Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran’s current president. Without reflection, I was filled with the excitement of meeting someone of such status. However, Ahmadinejad isn’t just a man of status. He is a man who is notorious for being a violator of human rights and one of the world’s most oppressive leaders. What did it mean that I was attending his event? How did my presence legitimize his regime and compromise my own morals about human rights?

Ten CISLA students majoring in International Relations along with Professor Forster and Professor Borer loaded onto a bus last Wednesday and headed into New York City. During the trip there, Professor Borer asked us to reflect upon the meaning of this upcoming dinner and what our attendance meant. The event, we all knew, had nothing to do with President Ahmadinejad’s interest in America’s youth but rather a PR stunt to improve Iran’s image in the world community as well as Ahmadinejad’s imagine in his own country. By going, we were supporting this effort. Clearly none of us agreed with his actions, opinions or policies. None of us were under any illusions going into dinner. We were using this as incredibly rare chance to speak with a head of state, a chance many of us would never get again. It was an extraordinary learning opportunity in which three years of government classes would come alive. The difficulty with which I struggled was that it was coming alive with what most people would view as a monster.

Earlier that week, we learned that students from Columbia University, another school invited, were going to stage a protest of their peers’ presence at the event. A student from Columbia explained that he “took issue with the moral implication of Columbia students sitting down to an off-the-record, intimate meal with an international pariah.” In a recent CNN article, activist David Ibsen stated that people attending the event “should be ashamed of themselves” since the event was merely “a propagandistic attempt by the regime to improve its image.”

Professor Borer pushed the conversation further and asked how we felt about smiling in a photo with the president. I can only imagine that such a photo would be used to prove that President Ahmadinejad wasn’t such a bad guy since so many smiling students from some of America’s top schools were interacting with him. We never did get the chance for a photograph with Ahmadinejad but the question still haunted me. Was the photograph with such a man over my moral limit? When I had first heard about the photo opportunity I was excited to have proof of the meeting. However, as I pondered the matter further I discovered not only would I probably not get a copy of the picture but I did not want it. I felt that this decision had established some sort of boundary but other questions still remained.

Was it wrong for us to go? Should we have upheld our morals and protested the dinner? Of course, someone else would have taken our place but it would have been our small way of objecting to his policies. Perhaps our presence and our questions would serve as a reminder to Ahmadinejad and others like him that the citizens of the world—even privileged college students—are watching him and know what he’s about and that he’s not fooling anyone. Or perhaps I need that rationalization, I’m not sure of any of this anymore. But it is a good question to ask one’s self: Where is my line? Would I have dinner with Kim Jong-Il? Pol Pot? What about Hitler? Are there seats in hell for enablers? And as I pondered those weighty issues I stepped off the bus and walked into the hotel where I was to associate with a very, very bad man. •