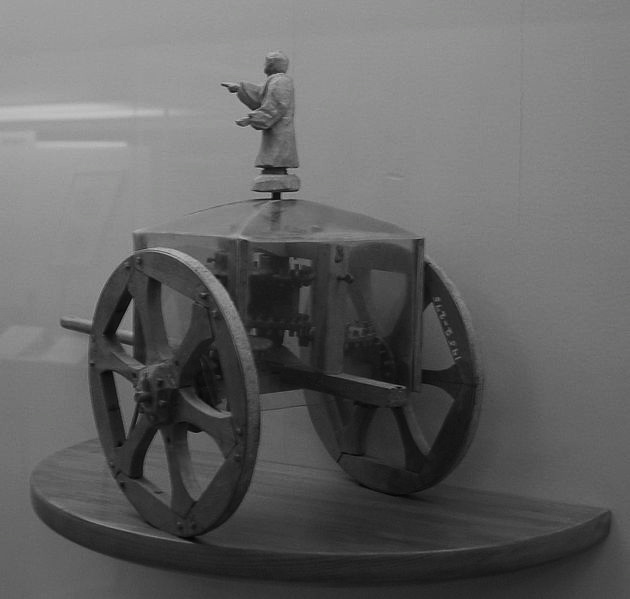

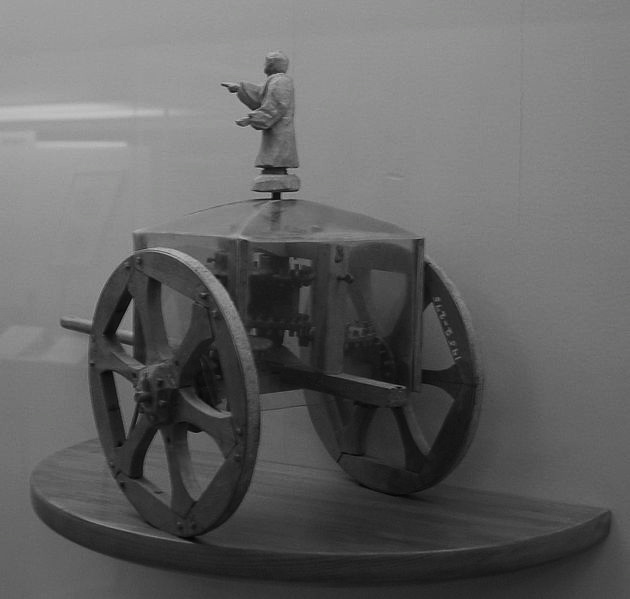

Last Tuesday afternoon, the math department hosted a short talk entitled “South Pointing Chariot: An Invitation to Geometry.” Presented by Stephen Sawin of Fairfield University, the talk began with a brief historical account of the chariot and a mathematical analysis of how it functions. A south pointing chariot is a small, wooden device with two wheels and a rotating pointer on top of it. An assembly of gears causes the pointer on top to rotate when the wheels of the chariot turn at different rates, so that the pointer always points in the same direction, regardless of the chariot’s orientation. Interestingly, since the relative distances that each wheel travels determine the direction in which the pointer points, the chariot only works perfectly on a completely flat surface. Traveling over hills, for example, can cause the pointer to rotate even though the chariot’s orientation might not have changed. Even the curvature of the earth can cause big changes in the direction of the pointer.

The idea originated from an ancient Chinese myth involving a hero, an army and a magical mist, but nowadays anybody can make one with a large enough box of Legos and a little knowledge about how to put the gears together.

For instance, imagine making a long journey with a south-pointing chariot on a perfectly spherical Earth. Start in South America, on the equator, with the pointer pointing southward. Travel directly north to the North Pole; the pointer will still be pointing in the direction from which you came. From the North Pole, turn ninety degrees to the right, and then travel south until reaching the equator somewhere in Africa. For the entire second leg of the journey, the pointer will have been pointing to the west. Finally, travel west from Africa until you reach your starting point again. But now, the pointer is still pointing west, a full ninety degrees away from where it started! This change is called a holonomy, and is a kind of measurement of the curvature of the earth.

These kinds of ideas are some of the foundations of modern differential geometry, and they have a lot of interesting implications. One example is that the trajectory of an airplane on a world map almost never looks like a straight line, but instead appears to be curved for no reason. In reality, this type of curved path, called a geodesic, is actually the shortest distance between the two points, because it follows the curvature of the earth. Putting a map of the spherical earth onto a flat surface always introduces some level of distortion, even on special kinds of maps that try to correct the problem. As a result of this distortion, the shortest possible plane flights might look longer on a map.

As a student interested in mathematics and some of the more numerical sciences, I found the presentation intriguing and I hope that the math department will continue to host similar events in the future. The humanities departments at Conn are definitely getting a bigger slice of the pie, and they host a lot of talks with topics that sound really specific and obscure.

Now, I don’t have anything against these kinds of talks; I’m sure there are students who find the topics far more interesting than I do, but I’d love to see the math and science departments respond with some more obscure presentations of their own. Why can’t we have more talks about advanced quantum physics or geometry in four dimensions? Talks are great opportunities to learn about unique topics from scholars outside of Connecticut College, but math and science students unfortunately seem to have fewer of these opportunities available to them. This is a liberal arts college and I think that the humanities and sciences should peacefully coexist here, each with their own distinctive talks that interest only certain students.

In my senior year of high school, the math department decided to start a division of the Math Honor Society; I was among the society’s first group of members. The speaker at the induction ceremony was Richard Zang, a math professor from the University of New Hampshire. Professor Zang spoke for a little over half an hour about the subject of Steiner points, a type of center of a triangle that has the interesting property of minimizing the distance to each of the triangle’s vertices. His presentation was excellent, not only because of his charisma, but because of the accessibility of the topic. Anyone who knew what a triangle was could have followed everything he was saying, and yet he also managed to intrigue the students who were about to become the school’s first members of the Math Honor Society. This is exactly the sort of thing that can be so awesome about a small liberal arts college. The humanities and the sciences don’t have to exist independently from one another; the students of both fields can instead find common ground.

In all fairness, too many lectures on difficult or inaccessible topics could quickly become tiresome, but occasional talks like “South Pointing Chariot” that require some advanced knowledge are certainly welcome. I’ve recently heard a lot of things from professors in the sciences about their departments hosting a series of talks this semester, and I can’t wait to see what they come up with. Little events like these are great, and I urge everyone to go to any talk that seems appealing to you. It’s usually time well spent if you have an hour or two of free time on your hands. •