Dance professor David Dorfman has been busy this past year, touring with his company, David Dorfman Dance, and premiering their latest show Prophets of Funk, a tribute to the great funk/soul band Sly and the Family Stone. Recently, the company performed at the Joyce Theater in New York to critical acclaim and five full houses — the last two shows were sold-out. Dorfman, who received his

MFA in dance from Connecticut College in 1981, talks about his past, present and future in the world of dance.

College Voice: When did you begin dancing?

David Dorfman: I received my undergraduate degree in business from Washington University in St. Louis. My junior year of college, I spent a year away at the University of Illinois, which is where I took my first dance class. It was the second semester, and I finally got the courage to take a very beginning level class, and I loved it. When I returned to Wash U to graduate, I got involved in productions there. After graduating, I danced as much as I could. I would jump in my car after work, and at class take off my business suit and put on leotards and tights, dance attire that I wouldn’t be caught dead in now.

CV: What did you do in the time between graduating from Washington University and beginning Connecticut College?

DD: In those two years, I was involved in retail management. I was an assistant buyer, an assistant department manager, and then I was involved in management consulting. But what really made me happy, satisfied and motivated was the dancing I was doing. I like to call them my wondering and wandering years.

During that time I met Stuart Pimsler, a newly minted MFA from Conn, when he came with his dance partner to Wash U as a guest artist. I got to know him, and found out that Martha Myers, the dean of the American Dance Festival for many years and the head of the Dance Department at Conn, had placed him on his new path. He said, “David, if you’re serious about dance, you should meet Martha.” I did that right away. I reached her by phone and she tried everything in her power to dissuade me, touting the difficulties of surviving in the field.

CV: So what did you do?

DD: I listened politely and I asked when I could meet her in person. Since I still so badly wanted to do it, I auditioned with Myers in Milwaukee. She invited me to Conn as a part-time graduate student. I did a summer study at Conn in ’79 and studied everything I could, reuniting with an important mentor, the late Daniel Nagrin. It was just fantastic. It just worked out. I’m one that perseveres. And to this day, Martha and I are great buddies.

CV: Where did you go after you received your MFA?

DD: I didn’t tell anyone I had an MFA until about five years after. I felt I needed New York training. I had invited choreographer Kei Takei to be an adjudicator for my master’s thesis, and she invited me to join her company after I graduated. I danced with her for three years. I immediately went on tour to Hong Kong with her; that was my first big trip. I spent a number of years with the wonderful Susan Marshall’s company as well. When an opportunity for alums to come back to Conn occurred, that got me reinvigorated about my own choreography. I brought a piece here and never looked back. In 1985, I formed my company, David Dorfman Dance. In ’86, I got my first grant from the New York Foundation for the Arts. It gave me a boost, some forward momentum. In the mid-90s, I worked as a guest artist at Conn for the first time.

CV: You said you enrolled in your first dance class your junior year of college. Were you interested in dance before then or was it just a risk you wanted to take?

DD: It was both. I was always interested in dance. I have distinct memories of using a baseball bat — I was a big athlete; baseball was my sport — as a fake microphone, imitating James Brown. I watched Soul Train when it was a really low-tech show in Chicago before it moved to Hollywood. I watched everything that had dance on it. When I was around eight, I remember pulling on my mom’s apron and telling her that I wanted to start a dance school.

I took a ballroom class in seventh grade, but I lost the courage in high school. I couldn’t get myself to try out for West Side Story. When I quit baseball in college, I missed kinetic behavior. I started peering into theater and dance rehearsals at school. Lucky for me, my best friend in college knew the theater people and I was able to begin reuniting with myself. Kei Takei often called the key creation and performing a moment of “aliving.” I was having mine at that point in my life.

At that time, disco was happening. I saw Saturday Night Fever at the theater when it came out. I had large hair and platform heels, and starting dancing disco during sophomore year of college. Junior year, I started competing in contests. I was doing the hustle like nobody’s business. I got second place in one contest and thought I was something else.

CV: What attracted you to disco?

DD: I really liked the social aspect of disco. You talked with your partner and shared dance moves with other people. It had an urban feel. I was brought up in suburban Chicago on the edge of the city, and I would go to the clubs in the city, so it connected with the urban part of me. When I went home [from college] for the weekend, I would have two or three platform heels and a baseball glove or two with me.

CV: Who or what else influenced your growing love of dance?

DD: In the dance class I took junior year, I found theatricality in dance. Theater majors had to do it for a requirement. I saw glimmers of potential with humor, speaking and a strong physicality bordering on slapstick and vaudeville.

There was a burgeoning repertory theater scene in Chicago, Steppenwolf Theater among them. I would go down to see those shows. Experimental theater combined with movement really had an appeal to me.

At Conn I met the right people who were interested in theatrical approach to movement. I met Annie-B Parson (now co-director of Big Dance Theater in NYC) who was a classmate of mine at Conn, and also from Chicago. I also met Chuck Davis (on my first summer trip to ADF), an incredible figure in African dance in America. He heads his African American Dance Ensemble in Durham, NC and is regularly responsible for Dance Africa at Brooklyn Academy of Music.

CV: What was your inspiration for Prophets of Funk?

DD: Right around that era, as a high school student, I remember working out in the basement of my friend’s parents’ townhouse. We were both really into sports, and we would work out with weights to 8-tracks of Sly and the Family Stone. Songs like “Everyday People” and “I Want to Take You Higher” were fervently inspirational. It was really good music to listen to.

My first week of college, Sly and the band was hired to play an outdoor concert. I can still see them on that stage. They were celebratory, bigger than life. They had black folks and white folks, men and women — even a female trumpet player (radical in

1973). They were influential from the word “go.”

Four years ago, I saw The Family Stone advertised at the Wolf’s Den at Mohegan Sun. I jumped in my car. They had three of the original

members. They were fantastic. That began the saga. On my drive home, I thought, “I’m going to do a dance to the[ir] music.”

I had gotten to know [Conn Professor] David Kim. I told him my idea over dinner, and he asked if I was sure that it would be just Sly’s music — if perhaps I wanted to get a bunch of funk artists. I told him I wanted Sly’s music, and I wanted a chance to get the band to play live with us. Kim said he had been thinking about Prophets a lot, re-reading recently Abraham Heschel’s Prophets. We asked, “Were Sly and the band really Prophets of sorts?” From that, we came up with the title Prophets of Funk.

I had called the band’s manager, who didn’t end up being the band’s real manager. But again, we persisted, and started getting somewhere with our idea. We got a hold of a wonderful producer in New York, and last August, we performed a Prophets of Funk – Live Concert Edition to about 4,000 people at the Lincoln Center Out of Doors Festival. It was a giant, giant thrill. We had gotten to know the band, especially saxophonist Jerry Martini, and the whole experience was inspirational for our company.

Earlier in the year, we needed verbal permission from Sly himself to use their music. I found the right person to give me his cell phone, and Sly and I talked a few times. He agreed happily to our request. I’ve been really lucky. It’s like a childhood dream come true.

CV: How can Sly and the Family Stone’s message apply to 2012?

DD: We all want to make it a better world in many ways. We try to inspire with dance and art. Some of those hopes and dreams are still alive. Sly and the Family Stone were prophesizing. They were talking of a better world. We can still listen to them.

I also like exposing young people to this music. Very few college-age kids know music from Sly and the Family Stone. A lot of people are going to look them up now.

We’ve taken the dance to some unusual venues. We’ve played tenminute excerpts for art galleries and middle schools. We’re getting to

communicate with a lot of different audiences. We even auditioned for America’s Got Talent in D.C. We got a first callback.

CV: Can you describe your part in the performance?

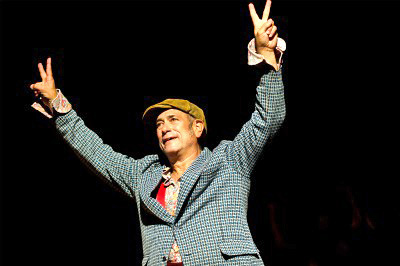

DD: At my age, I still want to be involved in dancing even though I’m twenty to thirty years older than the rest of the company. I don’t want to make a nuisance of myself, but the pieces we’re doing now contain a lot from my memory and my youth. So, if I can find a part in the dance, I go for it. At a preview of this dance in Nashville, I played a drum kit. It almost meant to look like I was trying to fill in as the drummer. By the time we premiered the dance at Conn, with the help of the company and our creative team, I had found my part.

Raja Kelly ’09 plays Sly Stone. He looks just like Sly. On some of the video footage, you think it’s Sly, but it’s Raja. I love that he’s a Conn grad. In one section, we do this duet on the apron of the stage. I’m gesturing to Raja and winking at the audience. I think subtext, content and context are really united. I’m this white Jewish guy who loves music and dance. I’m the director of the company, so it’s

kind of real life, kind of exaggerated. I’m showing off to everyone this great, young African American talent. There are good things to it, but there’s also kind of a rub to it. The audience could be asking, “Isn’t he taking advantage of this black artist? Does he really love him?” It’s complex, just like any relationship where you’re getting something out of it. Sometimes it’s hard to define who’s getting what at any given time. We’re trying to represent on one level, joy and fun, but also potential darkness as well.

CV: Do you have another project in the works?

DD: Prophets of Funk is part of a trilogy of projects, which includes Underground and Disavowal. These pieces are all centered on historical figures and key times in our nation’s history. I’m going to stay in a similar period with our next project on Patti Smith — poet, musician, artist, photographer. We’re looking at her take on joy, loss and hope. Her resilience and renaissance is incredible now. I’ve spoken to her several times. I love hearing her speak and sing, and I loved reading her book Just Kids. We’ll focus on her New York City in the late ’60s and now, and use her music. We’ll preview the event here in the OnStage series in Palmer Auditorium in February 2013. Our big New York showing will be at the Next Wave Festival at Brooklyn Academy of Music in the fall of 2013.

CV: What did you think of your review in the New York Times?

DD: I’ve had reviewers call me everything from “chunky” to a “hardware salesman,” but I care more about how my dancing is than what I look like. We all want the rave in the New York Times, but reviewers come in with their own agenda and their own desires. I thought the writer got at some of the complexities of the piece when he asked the questions he asked. We’re always going to disagree with something in a review. And sometimes the critical parts of a review are valid comments — ones worth heeding. There are sections of the dance that I still want to make stronger. Art doesn’t answer questions. It starts the conversation. If our work can get people talking about the world, then we’ve done our part.