As a senior who witnessed the chaotic arrival of first-year students, my first day at Connecticut College seems like a blur. I remember, with both fondness and embarrassment, getting my “old” Camel Card with a picture of me looking away from the camera and being unable to understand why our orientation had an abundance of picnics and bagpipes. What seems even more unfathomable at this point is to remember back to my senior year of high school.

Throughout high school, I chose career goals the way a five-year-old picks a Halloween costume. Despite all the pressures it presented, getting to college seemed like the embodiment of adolescent success, the universal gateway to the “right path” that would guide me to the rest of my life.

Since I was unsure what that path would be, Connecticut College’s liberal arts education seemed like the best fit as a community of students engaging and exploring their interests in order to pursue whatever it is about which they are passionate.

A major milestone in this journey for many Conn students, myself included, is the opportunity to study abroad. According to the Office of Study Away, over half of the junior class studies abroad for at least one semester, and in 2009, Connecticut College received the prestigious Paul F. Simon Award for Campus Internationalization.

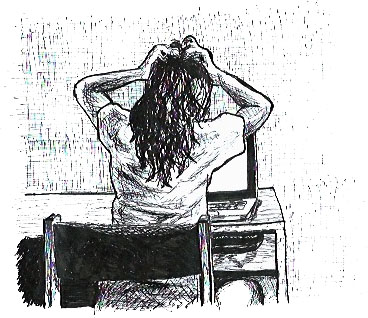

Yet my decision to study abroad, while initially cause for excitement, later became a source of increasing anxiety as my departure date approached. Not only did I fear the practical realities of communicating in a foreign language, but also the more abstract preoccupations that my semester abroad came to signify. For me, my semester abroad became the first tangible moment in college where I wondered: “Am I making the right choice?”

When we choose our courses, we are faced with numerous and often slightly overwhelming possibilities. We have this magical thing called “the Add/Drop period” where we get to voluntarily switch out of classes we do not like.

During a semester abroad, however, and particularly when you choose a program with a set curriculum, there is no other option. You are there, in your country of choice, for the full four months you committed to, often without the opportunity to return home until the program ends.

I made the decision to study abroad in a country I never imagined myself studying abroad in because I wanted to push myself outside of my comfort zone and have an adventure. My study abroad program seemed dynamic, immersive and presented opportunities to study and travel in multiple cities. Focused on both policy and education, its academic premise reflected the areas of interest I had most strongly explored at Connecticut College.

While abroad, I had countless rewarding and exciting experiences: I formed incredible connections with my host families and fellow students, adventured across two countries, participated in marches for equality, and even accidentally swan-dived in front of a city bus while crossing the street. Yet, there were also parts of my program that bothered me, challenges I did not expect and a sense of unfulfillment.

The perception on campus is often that studying abroad is supposed to be a truly transformative experience, where students return from abroad “knowing more about themselves” and “truly understanding who they are” while simultaneously feeling an unwavering sense of emotional attachment to their host country – none of which I seemed to feel.

Other students explained why they chose this particular study abroad program focused on policy and education. Many of them responded with aspirations of becoming teachers, lawyers, Foreign Service Officers or improving their foreign language skills – all of which are noble pursuits. As I listened to their answers, however, I realized with a sinking feeling that none of their responses applied to me, even though I thought they once had.

This revelation shocked and scared me because as I reflected back on my wider college experience, I discovered that in pursuing these particular interests, I had neglected other equally important parts of myself, the parts that made me truly happy. My personal reflections since returning from abroad have certainly been formative, but mainly because they have helped show me what it is I do not want to do, rather than what I do.

These revelations would have happened anyway, regardless of my decision to study abroad, though that semester became a catalyst that allowed them to happen. That summer, I chose to return to an organization where I had previously interned to complete my CELS funded internship, choosing familiarity and an atmosphere I enjoyed over another opportunity to try something new.

The field in which I interned this summer provided countless good experiences and is a job I know that I could do and do well, but also know wouldn’t make me entirely happy.

My return to campus this August made me increasingly anxious. In addition to the pressure I place upon myself, I feel there is also an unspoken expectation of seamlessness, that the path of major, minor, center, study abroad and funded internship are supposed to fit together.

Now, as a CELS Fellow, I inherently know that this is not true. I regularly meet students that have interests scattered across the board and struggle to decide which ones they want to explore. I also hear stories of alumni changing career paths, returning for the invaluable resources CELS has to offer all current and past Connecticut College students. Even though I knew these things, I still experienced an overwhelming sense of terror and isolation when it became my life, my plan and my goals that changed as I entered my senior year.

The Princeton Review recently recognized Connecticut College as one of the top colleges for career services, distinguishing the CELS Program amongst those at other colleges across the country, and rightly so. One year out from graduation, 96 percent of graduates are employed or pursuing graduate degrees, an immensely impressive statistic for such a small school.

What is important to remember, however, is that this statistic shows a formidable result, instead of the equally formidable journey that led to it. Amidst our alumni network are history majors who became doctors, religious studies majors who became realtors and biology majors who became librarians. Not all the paths to post-grad life will be linear and the right ones will be whatever ones we end up on, whether we envision them or not.

As my Dove Chocolate note once told me, “You are where you are supposed to be.” That place is here at Connecticut College with my fellow seniors whose diverse experiences continue to set Conn apart from other institutions. College continues to be the same gateway I imagined it would be, as difficult as that is to remember when post-grad realities await us.

The liberal arts experience does not end upon graduation, but is merely a transition point that prepared us with a skillset that will lead us to our next exploratory adventures. My post-grad adventure may not be the one that I thought I planned and it may not be the one that I stick with forever, but I am excited for where it will take me, wherever that may be. •