At the Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, there is a section of the Rolls Down Like Water: The American Civil Rights Movement exhibit that is designed to look like a lunch counter. A row of swivel bar stools, finished with chrome and colored seat cushions, faces a large rectangular mirror, reminiscent of a two-way mirror in TV police interrogation rooms. Along the bottom rim of the mirror is a red analog clock that marks the passage of time for the person sitting on each stool. On the counter are pairs of handprints and a set of directions instructing participants to place their hands over these marks, put on the pair of headphones, close their eyes and remain seated for as long as possible. They are about to experience a simulated sit-in.

Sit-ins are a defining image of the Civil Rights Movement. So mythic, in fact, that because we have long been taught of their successes, it can be easy to overlook the courage needed to perform such a seemingly simple act. Participating in a sit-in was not simply sitting at a lunch counter and refusing to get up, but also having the determination and will-power to remain in an environment clouded by intimidating threats of physical violence.

When I sat at that counter and put on those headphones, the first thing I heard was a whisper. It was a whisper that grew into a statement, then a shout, then a chorus of deep, male voices screaming at me to get out, to know my place. The sounds of breaking plates, the feeling of boots kicking my chair, the vibrations of chaotic human movement radiating upward from the ground: these are the experiences lived by the activists who risked their lives and safety to protest an unjust and discriminatory system.

When I jumped and removed my hands from the counter, I looked at the clock to see how much time had passed. The clock read 1:47. My experience of a simulated sit-in lasted under two minutes, and it never would have happened without the funding received from Connecticut College to turn a 400 level seminar into a TRIP (Travel Research and Immersion Program) class.

At Connecticut College, TRIP classes are faculty-driven efforts to integrate travel opportunities into their syllabi and expand learning experiences beyond the classroom. The Traveling Research and Immersion Program allows professors to submit proposals to receive college funding to include short travel experiences of one to three weeks to domestic and international locations. Occurring during mid-semester breaks or immediately after the semester ends, TRIP courses present students and faculty the opportunity to study away from campus, directly immersing them in relevant material. TRIP classes represent just one of the many ways Connecticut College fosters an emphasis on experiential learning: connecting academic learning with hands-on activities that enhance understanding.

My trip over fall break to the Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, Georgia resulted from my surprise enrollment in a TRIP class during the first semester of my senior year. When I registered for HIS 460: Black Freedom Struggle last spring, I had no idea that it was a TRIP class, only finding out it was when I returned to campus in August. An upper level history class on the Civil Rights Movement, it reexamines the historical narrative by analyzing who is included and excluded, our collective remembrance of the movement and by asking how far we’ve really come. By constructing the Civil Rights Movement from the ground up, our class has worked over the past semester to expand the history of the movement for civil rights to incorporate the fights for economic equality, justice for sexual assault victims and equal representation in popular culture.

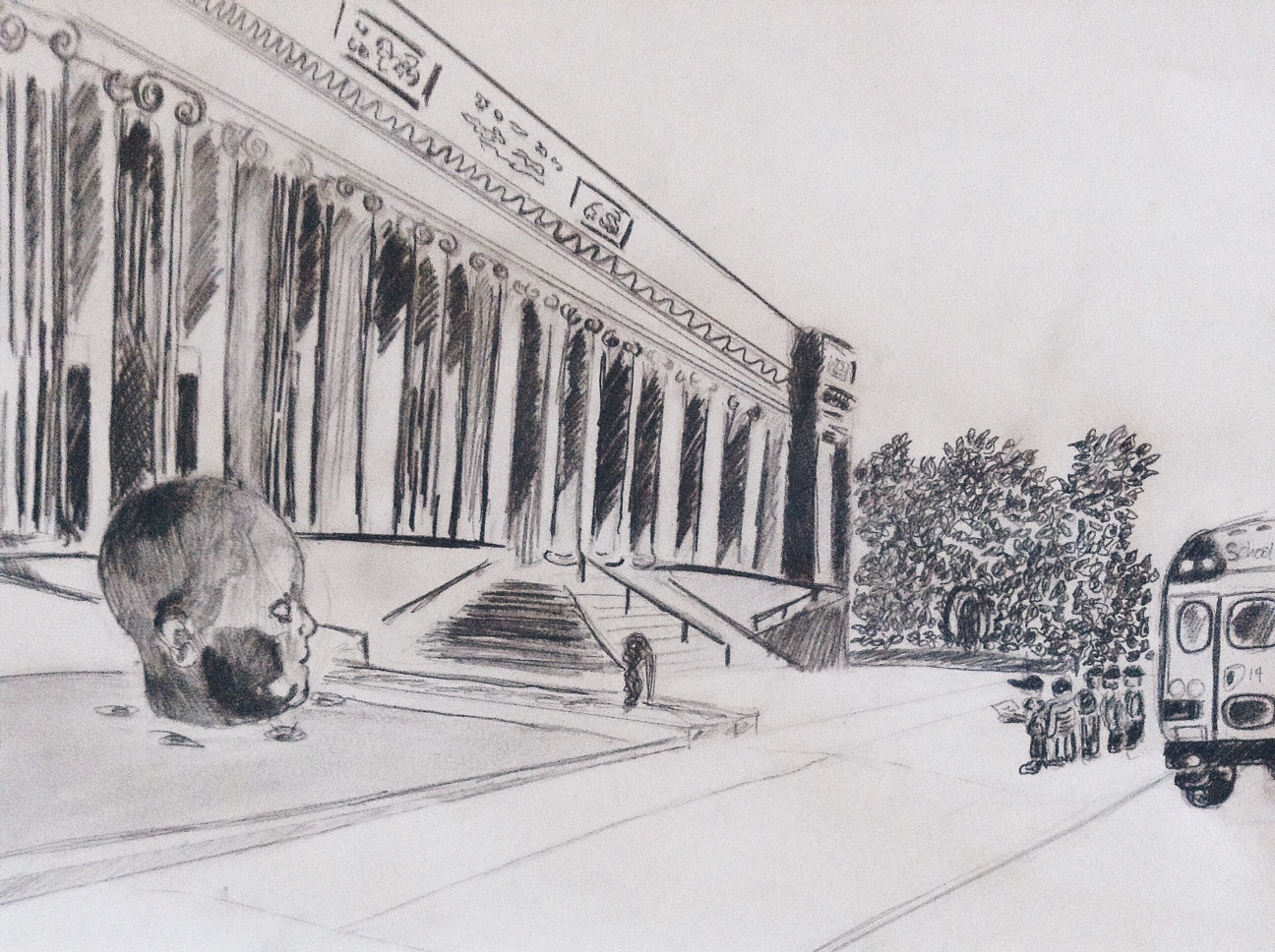

Traveling to Atlanta gave us the chance to explore the history of the movement in one of the cities that defines it. In addition to visiting the Center for Civil and Human Rights, we also visited the Apex Museum and toured Martin Luther King Jr.’s childhood home on Auburn Avenue – once called “Sweet Auburn,” a hub of African-American owned businesses in the 20th century. As a class, we even got to go to the Robert W. Woodruff Library at Clark Atlanta University and conduct research for our final papers using the Martin Luther King Jr. archives collection. The opportunity to look through the digitized collection of King’s own papers was more than just searching for primary sources. It was an opportunity to reexamine the words of a man whose legacy helped transform a nation.

These experiences undoubtedly contributed to our understanding of the course material, but perhaps the most useful parts of our TRIP were the conversations we had with each other and other students throughout the weekend. During an organized book talk with Dr. Akinyele Umoja, the author of We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement, whose book we later read in class, our class of seven got an inside look into not only the making of his book, but also the prevalence of armed resistance in the Civil Rights Movement from one of the foremost authors on the subject.

As an alumnus of Morehouse College, our teacher, Associate Professor of History David Canton, also organized a roundtable discussion with students from both Morehouse and Spelman College to discuss contemporary issues of race and racism. From Ferguson to Ray Rice to sexual assault on college campuses, our roundtable discussion questioned the existence of corporate social responsibility, the oft-ignored economic and emotional factors in domestic violence and the idea of the United States as a post-racial society. Our discussion reflected the conversations Connecticut College, and The College Voice, are working to inspire on our campus. As one of two white students in the room, I found myself examining the weight of my words and my opinions in an effort to recognize my own privilege, not only in that room in those moments, but throughout the entire weekend and in the every day experiences of my life as a white woman in the United States.

TRIP classes at Connecticut College offer students and faculty unique opportunities to travel to places that directly relate and even inspire course material. They allow students to connect the academic ideas and concepts of their classes with research and hands-on experiences that transcend the physical boundaries of a classroom. While the main focus is academic, there are of course fun perks, too: Gladys Knight’s Chicken and Waffle House, Atlanta nightlife and seeing my professor sprint across an airport terminal were all unquestionable highlights. But above all, TRIP classes ensure that students and faculty are learning by doing; taking their liberal arts education out into the world and acting upon it – exactly what our classes at Conn should be preparing us to do. •