The audience at Atwood’s reading in the packed 1941 Room in Crozier Williams. Photo courtesy of Sophia Angele-Kuehn.

The 18th Daniel Klagsbrun Symposium on Creative Arts and Moral Vision took place on Nov. 3rd in Crozier-Williams.

The Symposium started in 1989, and although not annual, it has allowed the College to bring in important literary figures. Past speakers include Elie Wiesel and Michael Cunningham. This year, it was the famed author of The Handmaid’s Tale Margaret Atwood.

Connecticut College’s Weller Professor of English and Writer-In-Residence Blanche Boyd opened the event with providing some background information on Atwood. When considering who would be featured at this year’s Symposium, she asked herself, “Whom would I really like to talk to?” Boyd hosted “The Courage to Imagine: A Conversation with Margaret Atwood” with the author earlier that day.

Atwood, Canadian-born, wrote her first novel at 24. Her first attempt however wasn’t initially published. With determination, she eventually won the Booker Prize in 2000 for The Blind Assassin. Besides The Handmaid’s Tale, she has published a graphic novel called Angel CatBird, a retelling of the Odyssey through Penelope’s eyes in The Penelopiad, and a modern version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest in her newest release Hag-Seed.

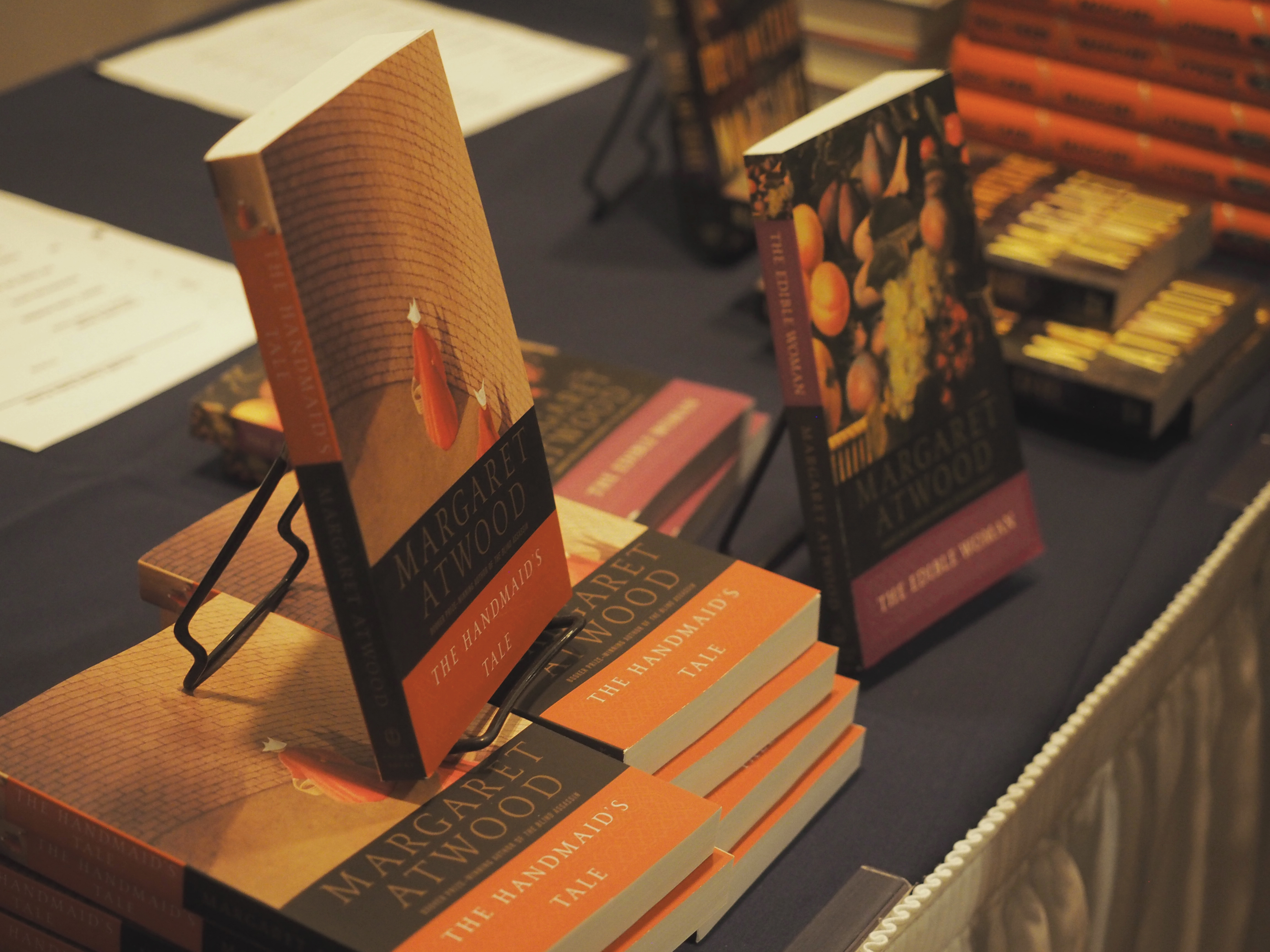

Atwood’s books on display at the reading. Photo courtesy of Sophia Angele-Kuehn.

“There are not many that write a lot of books that are consistently good, much less dazzling,” noted Boyd at the podium. Additionally, “She assumes that you’re smart.”

“Someone came up to me and said, ‘She saved my life.’” Another friend of Boyd’s told her, “She’s a genius!”

When the author herself finally came up on the stage to much applause, she began, “Thank you very much. I’m not a genius.”

Her very witty talk started with a summary of her first graphic novel and the hard work behind it. She has always enjoyed drawing comics both as a child and as a grownup. Her love of cats and concern with the declining species of birds spurred her to put this “hard-cover comic book” into publication. After going through many graphic artists to find the look she wanted, making and sending idea sketches to the chosen Johnnie Christmas, and coming up with an origin story on Angel CatBird’s pants, she eventually produced a colorful story that centers on identity conflicts. Angel CatBird, published last September, promptly debuted on the #1 New York Times Bestseller list for comics and graphics. Volume 2 will be published this coming February.

With regards to Hag-Seed, Atwood knew she was going into “risky business.” She explained, “If you really mess it up, the Shakespeare nuts will be on you.” When she was first given the opportunity to retell a Shakespeare play, she selected The Tempest right away. This was followed by extensive close-readings – a process Connecticut College English students know all too well. Atwood even referenced different editions and watched numerous adapted films and recorded plays.

She selected The Tempest because it is a revenge story that ends with forgiveness. The previously wicked sorcerer Prospero, after being forgiven, proclaims at the end his “freedom.” This led Atwood to wonder – what was imprisoning Prospero all this time? Thus came the inspiration for her story.

Hag-Seed centers on the main character Felix and his career teaching literature to a correctional institute. After being unjustly fired from his previous job, he plots his revenge.

It was here that Atwood put on her red glasses to read from the book. The first passage concerned a conversation Felix has with a young, turned-down Shakespearian actress. The second reading was about an idea one of the inmates has on livening up the drawn-out Act I, Scene 2 of Felix’s own production of The Tempest with a rap and choreographed dance.

Margaret Atwood signs books for Blanche Boyd. Photo courtesy of Sophia Angele-Kuehn.

The 76-year-old author surprisingly kept up the rap easily: “He was the duke, he was the duke, he was the duke of Milan.”

The audience, packed into the 1941 room, was enraptured and attentive throughout, laughing often at Atwood’s entertaining writing style. When the Q&A session arrived, she received a question of her view on the Booker Prize becoming eligible for Americans. (In order to be considered, the book has to be published in the UK). She proclaimed the whole situation “interesting” and proceeded to enlighten the audience with the odd history behind the Booker Prize originally being a British tea company.

A high school English teacher who used Atwood’s novels in class wanted to know her opinion on “correctly” interpreting in classrooms the metaphors in her work. Atwood advised the general audience, “Pretend the author’s dead – like Shakespeare. He won’t go on talk shows and ruin your term paper.” She also brought up a good point: “Once published, it’s in the hands of the reader.” Often in college humanity classes essays and reports center on interpretations – personal opinions have a say, but there is usually a “correct answer.”

Atwood however believes, “Everyone who plays music plays it differently… Interact with it – use your unique reading of the text.”

After I patiently waited at the subsequent book signing, Margaret Atwood opened up my copy of The Handmaid’s Tale and penned her signature. I told her my wish to become a great writer like her. She looked up. “Go for it.” •