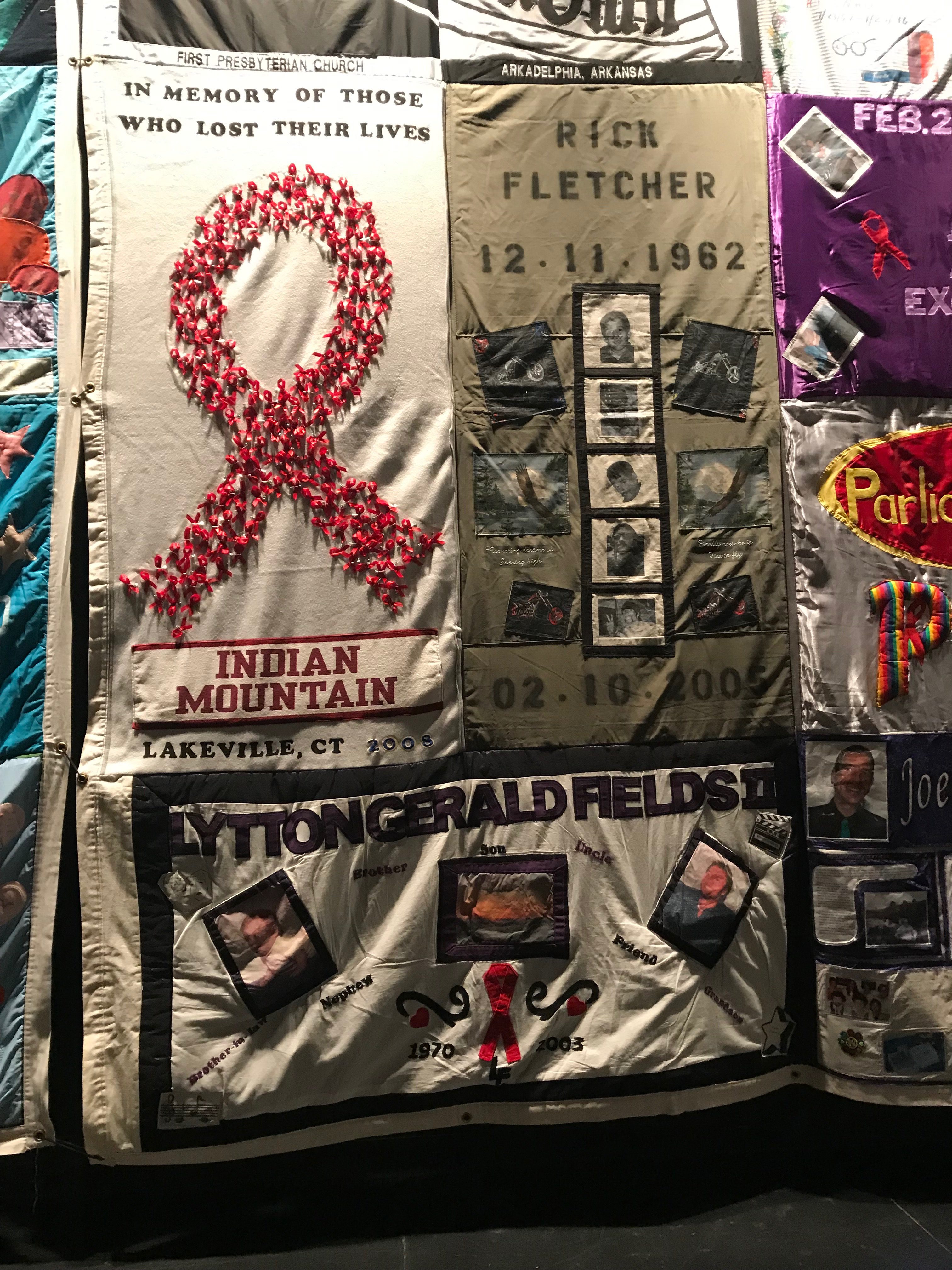

Two weeks ago, pieces of the NAMES Project Aids Memorial Quilt were put on display at Connecticut College’s Tansill Theater. These patchwork quilts were only a fraction of the 489,000+ panels collected over the years to honor victims of the AIDS pandemic.

The AIDS memorial quilt began at the height of the United States’ AIDS crisis in the 1980s as a response both to it and the lack of government action due to homophobic administrations. In 1985, gay rights activist Cleve Jones, while planning the annual candlelight march for the assassinations of San Francisco politicians Harvey Milk and George Moscone, asked his fellow marchers to write down the names of someone they lost to AIDS on a placard. At the end of the march, they hung these placards on the walls of the San Francisco Federal Building. To observers, it looked like a patchwork quilt. Inspired by this, Jones and other gay activists began planning a larger project– an AIDS memorial quilt put together by friends, family and lovers of AIDS victims. In 1987, Jones teamed up with Mike Smith and others to officially begin the NAMES Project Foundation. The quilt, from its beginning, has grown to be the largest community art project in the world. It serves as a reminder of the AIDS pandemic that has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in the United States since 1979 and preserves a history that gay rights activists feared would be erased.

Upon walking into Tansill Theater, I saw a television set up in the lobby playing Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt (1989), a documentary about the story of the NAMES Project Memorial Quilt and the lives of those affected by the AIDS crisis in the United States. The film even won an Oscar for Best Documentary, among other awards. Playing the documentary set the atmosphere of the exhibition, even though it was upstairs in the Black Box Theater, as it brought the story of the Quilt and the AIDS pandemic to life, especially to those who weren’t alive to experience it.

In Tansill’s Black Box theater, the 70+ panels of the quilt hung on the dark walls with harsh stage lighting illuminating the names of victims. This lighting was unfavorable to the higher panels, especially when photographing it. When I visited, it was almost silent in the theater despite a few people also observing, with only the squeak of shoes to break silence. The mood, of course, was somber, but the quilt said something different. Although heartbreaking, the panels speak of resistance, love, pride, and, most importantly, hope.

Although the sections represent the entire country, some of the panels on display were local, including ones from Stamford, Bristol, Danbury, Lakeville, and even New London.

What intrigued me the most were the designs on the panels and how they differed from one another. Some were simple while others had more intricate compositions. In the selection at Conn, there was a balanced mix between panels that used gay pride imagery including the rainbow, the triangle, and the red AIDS ribbon and others that refrained. The triangle seemed to be a very popular symbol for the time, but since then the rainbow has become a more mainstream symbol of gay pride. The triangle, though, is an homage to and adopted from the symbol used for gay men during the Holocaust–a pink triangle. Others used more religious imagery including doves, crosses, and prayers. On the one hand, the layout and elements of each panel depended on the creators of the panel, information not easily available to the viewer. Some may have felt that their sexual orientation was not necessary to highlight due to the stigma around HIV/AIDS as a “gay disease” while others may have felt more inclined to celebrate their loved one’s sexual orientation due to the United State’s inaction to the HIV/AIDS pandemic since it mainly affected the male gay community.

One notable panel at Conn was Roy Cohn’s. Cohn helped McCarthy lead the Red Scare in exposing communists in America and the Lavender Scare, which tried to expose gay, lesbian, bi+ and queer citizens during a time when homosexuality was illegal. Ironically, many people suggested that Cohn himself was gay, and he had several sexual relationships with other men but did not identify as queer. He died in 1986 due to AIDS complications, further adding to the suspicions around his sexuality. His panel was simple. His name was displayed in large lettering while underneath it read: Bully (in red, an allusion to the Red Scare), Coward (in a pink triangle, as a reference to him never accepting his queerness) and Victim (in gray, to remember his struggle with AIDS).

Having it here on campus is an important tribute to and display of solidarity with the LGBTQIA community. •