“Abracadabra” (2007). Photo courtesy of Sophia Angele-Kuehn.

In the German novella The Guest by Yoko Tawada, the protagonist walks through a flea market and picks up a book whose title is written in a circle instead of left to right. She asks the hawker what language it’s written in, and he shrugs, grinning, saying that it’s not a book, but a mirror: “To our eyes, you look exactly like this writing.”

This opening scene of the Kafkaesque story reflects on the experience of feeling like the “Other” in a new country and mastering a foreign language, whose peculiar words and letters the protagonist experiments with on a typewriter.

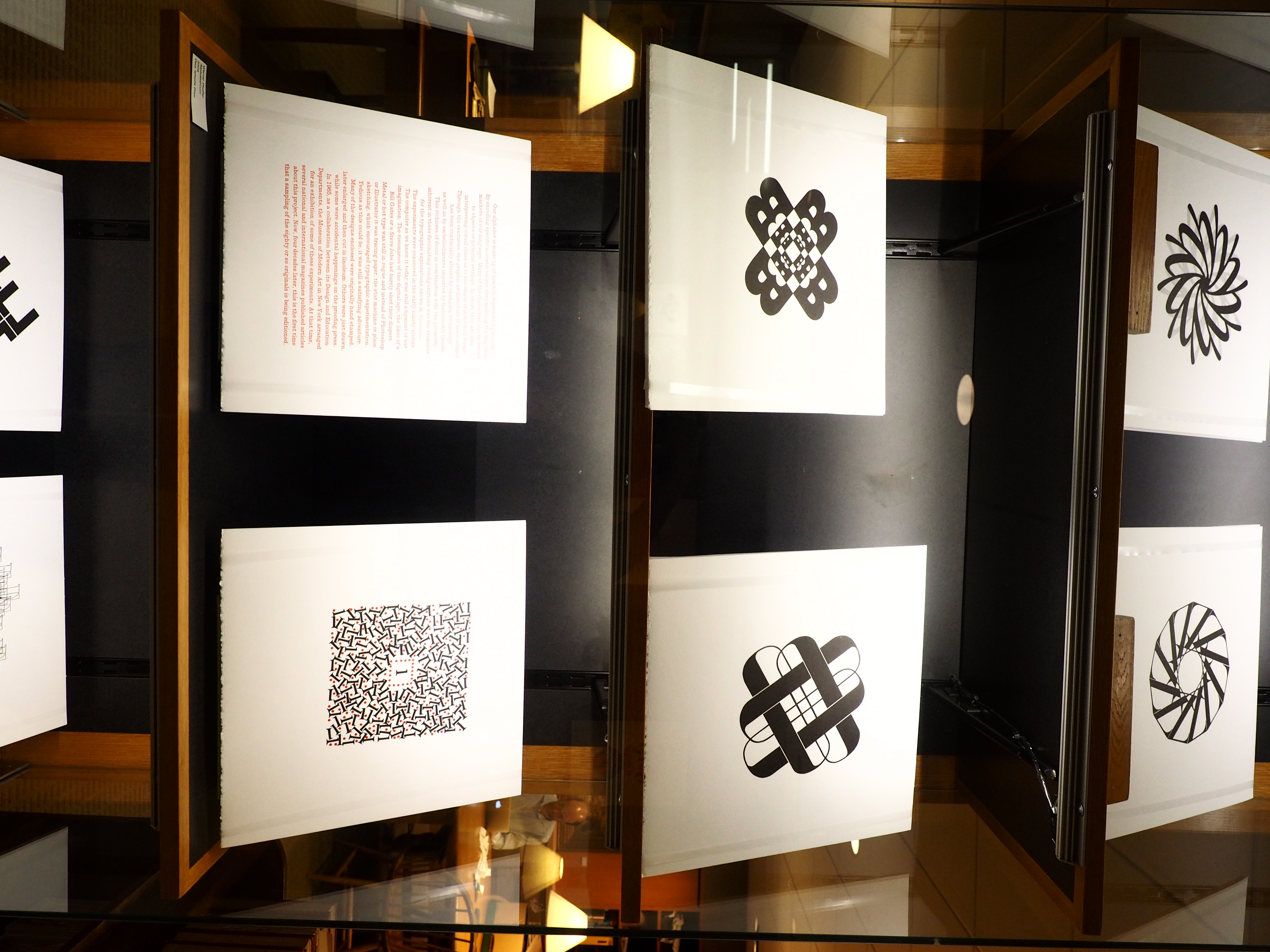

The typography, prints, and artist books produced by German-American artist Werner Pfeiffer also hold a mysterious, unreadable yet important message, as read in the circular-shaped Liber Mobile (1967). Four lithograph prints of the entire portfolio Liber Mobile (“Liber” means “book” in Latin and is the Roman god of wine and free speech) are displayed at the Linda Lear Center in Shain Library. They feature cut-outs that allow layering over other prints, which can then be rotated or moved underneath according to the desire of the user.

“They’re characteristic of [Pfeiffer’s] work – they’re really designed for you to play with … Each one is created with an eye towards the whole,” commented Ben Panciera, director of Special Collections and Archives.

Indeed, each print is reminiscent of the shape of an eye rolling around a pupil center, each uniquely coded and seemingly untranslatable once the “reader” looks closer and their eyes become adjusted to its strange language. In this case, letter form is the form of art. Colored letters, numbers and alphabet-based symbols come together and create larger shapes, made possible thanks to careful manipulation using letterpress printing. It makes one realize that the letters that one sees and interprets on this very page are mere lines and circles representing ideas, feelings, and physical objects, with a little serif flair at the ends.

According to the official summary accompanying the typographic prints, Liber Mobile is inspired by the work of philosopher Marshall McLuhan. “When I first came across Marshall McLuhan’s writings he was a trail blazer and visionary. He foresaw the change of our cultural matrix away from an alphabet culture to an image based expression. My Liber Mobile is a direct response to his thinking and is an ode to the end of an era,” commented Pfeiffer for The College Voice.

McLuhan is probably best known for his phrase “the medium is the message” in his 1964 book Understanding Media, arguing that the medium of a message and its characteristics is far more important than the message itself, by even influencing how the message is perceived. With Liber Mobile, the media is literally the message (pun intended) with language acting as the artist’s paintbrush. Using a similar media but perhaps a different message, a dozen hand-stamped prints from Pfeiffer’s Alphabeticum (2006) portfolio in Linda Lear manipulate the shapes of letters and numbers as what they are – shapes – to create intriguing geometric designs.

“Alphabeticum” display in the Linda Lear Center. Photo courtesy of Sophia Angele-Kuehn

Not too long after emigrating from Southern Germany in 1961, Pfeiffer became Professor of Art as well as director of Pratt Adlib Press at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. On his motives for the transition, he commented, “I was quite curious about the US. At the time it was a country full of hope and promises. After almost 60 years I naturally feel at home here.” He retired from teaching in 2002 to focus on being an artist and proprietor of Pear Whistle Press in Red Hook, New York. His books, collages, drawings, prints, paintings and sculptures have since then been shown both internationally and at the neighboring campuses of Vassar, MIT, Princeton, and Cornell, to great acclaim.

Several examples of Pfeiffer’s artist books and sculptures were featured in Cummings’ exhibit “Loose Leafs and Bindings: Book Arts and Prints” from Jan. 22 until Feb. 28. Curated by Professors of Art Andrea Wollensak and Timothy McDowell, the purpose of the exhibit was to highlight the interactive relationship between text and image and the importance of physical print in today’s Twitter and CNN-dominated society. This message was enforced by the presence of a massive Gutenberg press dominating the center of the sky-lit room, paying homage to the genesis of print technology, mass media, and consequently, western democracy. The walls were covered with words and books instead of paintings.

“Artists’ books are books that have been created by artists that explore and experiment and test the definition of what ‘book’ is… and a lot of them are not books at all,” explained Wollensak, guiding me past the display cases. “We’re challenging what a book is, working with very traditional methods, but also new processes. The laser-cut projects are digital fabrication, and we use the computer to compose the type … Really it’s about not using the internet, and that they’re very physical. Once the material is put in its form, that’s it, it’s not something that can be distributed digitally. I think there’s a resurgence in this direction, coming back to the importance of the object, and the politics of that kind of information control.”

Letterpress printing was invented by Johannes Gutenberg ca. 1450 in Germany, a thousand years after it had first been explored and used in East Asia. However, the importance of moveable type and visible language took hold in the western world, helping establish new religions, revolutions, and artistic and intellectual movements.

“Quite often books are exploited for expedience, to impose, to misguide and to manipulate. On the other hand the power of a book to spread free and unbridled thought renders it equally vulnerable,” writes Pfeiffer on Cornell University’s online exhibition of his work. Pfeiffer grew up with book censorship and public book burnings in Nazis Germany, and strives instead to create and cherish books rather than dismantle them: “The creation of a handmade book involves a multitude of dimensions which are not answered by typing a code into a computer. The bookshelf of the virtual world does not offer the thrill of holding a finely crafted piece of work to closely examine it, feel it or smell it. Or even blow the dust off it.”

Other displays in “Loose Leafs and Bindings” also pulled attention back to tactile artworks and the tools used to shape them. Featured were the works of the two Weissman Visiting Artists: blown-up pages from Italian graphic novelist Daniele Marotta and the research results of Emily Larned’s Impractical Labor in Service of the Speculative Arts (ILSSA) project on artists’ “essential tools for living.” Claiming a separate room were the wildly unique creations of students from Wollensak’s Artist Books class taught this past fall. Wollensak is also the Director of the Ammerman Center for Arts and Technology.

We approached a display case with Pfeiffer’s Abracadabra (2007), a collection of individual pages and 3D paper structures that can be folded and flipped, is an homage to the work of Dutch typographer H. N. Werkman who was shot by the Gestapo in the final days of WWII.

“This is Abracadabra, which is just a magical piece. And ideally you want people to handle it … it keeps changing,” gushed Wollensak. We both looked down at the pieces of paper that had been transformed into a still circus of letters.

In comparison, the accordion-style Zig zag (2010) is a kinetic structure built solely from folding paper and printed on a Vandercook press. It’s “a hands-on piece” that’s “best experienced by removing the centerpiece from the constraints of the box and by letting the construction inspire your interaction with the work”, according to the directions in the box. This touching and playful manipulating of the artwork, essential in reading books, is also essential in exploring Pfeiffer’s work.

On the last page of Yoko Tawada’s story The Guest, the protagonist separates the letter Z from the secluded German words on her typewriter: “… Blit z schlag / Net z haut / Z erplat z en.” Inspired and fascinated by writing this sharp-sounding letter over and over again, she attempts to discover its personal meaning for her.

“It is difficult to say what specially it is that inspires you. Something enters your field of vision, your subconscious, your emotions and keeps resurfacing,” replied Pfeiffer to my email. “If something comes back repeatedly and with enough clarity it is necessary to give it a try and develop an answer to it … At the moment I am fascinated by numbers, their history and their mystique. This curiosity will probably end up in a series of artist books.”

And as for his latest read? “Thank You for Being Late by Thomas L. Friedman. A fascinating book about thriving in the age of accelerations.” •