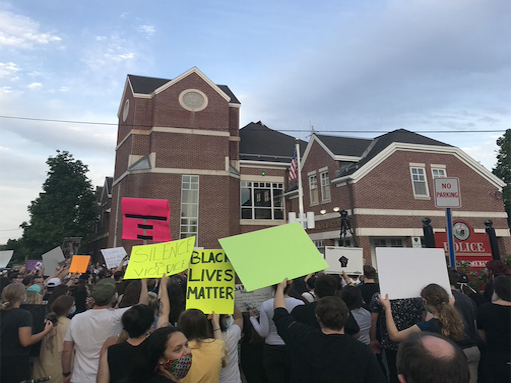

Photo Courtesy of Elizabeth Berry

Trigger warning: this article discusses black death, black violence, and white supremacy.

In my junior year at Connecticut College, I enrolled in Professor Hubert Cook’s English course Repetition which discussed repetition’s daily iterations (from the words we read to the images we see on the screen) in and on the lives of Black people in the United States. We raised questions about these repetitions and asked ourselves if we can make use of them, and if we can escape them. These questions came to mind when videos capturing the murder of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd flooded the internet in late February and May, respectively.

What does it mean to watch Black bodies be beaten, choked, and murdered? From a white perspective, it can be seen as a method to confront what whiteness has done to people which white supremacy views as inferior. This confrontation is paramount to dismantling systemic racism, but do these images always have the desired effect on the viewer? Does the mass circulation of these videos further inflict harm on the Black bodies which they depict?

Cicely Blain Consulting agency has a post on their Instagram (@cicelyblainconsulting) of an infographic listing “10 Habits of Someone Who Doesn’t Know They’re Anti-Black.” One slide discusses re-sharing videos of Black people dying: “the videos are essential. We need evidence, we need memory, we need fire for the revolution.” However, “Black folks do not need to see them; do not need to be scrolling through pictures of new shoes and make-up routines to come face to face with the last breath of someone who looks like them, someone who could be them in another life, or in this one.” This mass-sharing is necessary, but becomes triggering for Black viewers and raises the question: why do white viewers need to see these episodes of police brutality to understand Black Lives Matter and that racism persists in our society?

Melanye Price, author of The New York Times op-ed “Please Stop Showing the Video of George Floyd’s Death,” was 18-years-old during the 1992 Rodney King riots. There was a similar stream of videos of police brutality then as there is now after the murder of George Floyd by Derek Chauvin on May 25. Price argues these videos are necessary because they generate outrage. But she also points out that the continuous coverage leads to “snuff films with African-American protagonists.” Instead, “we should spread images of the victims that give us a fuller sense of humanity.” The death of Black people has long been treated as a spectacle; “white crowds saw lynchings as cause for celebration.”

I am not disagreeing with social media activism, or the necessity to share the documentation of police brutality, and neither is Price. After all, it was the graphic video of George Floyd which led to the arrest of Derek Chauvin and the three police officers who were bystanders in the murder. Instead, she asks if this loop of footage––the death of Floyd’s death which was caught on camera––is having the desired result on the viewer. Ultimately, “anyone who needs one more video to believe the injustices around us, either refuses to learn or is content with the violence.”

Siraad Kalila Dirshe also posted a helpful infographic to her Instagram @sirdshe which touched upon resharing posts responsibly. She suggests holding back from sharing graphic videos or images: “circulating violent images is traumatizing and emotionally debilitating to the groups of people the video affects (historically, black, indigenous, and people of color).” While circulating videos of police brutality documents the criminal acts committed, it is important to reflect on the intention behind resharing these videos and the impact they may have on black people. In an interview with Lisa Lerer of The New York Times, Senator and vice-presidential prospect Kamala Harris credits the smartphone with stimulating the current political shift in regards to racism in the country. She says, “because of the smartphone, America and the world are seeing in vivid detail the brutality that communities have known for generations. You can’t deny. You can’t look away.” Smartphones hold incredible power, but with power comes responsibility about how we post, stream, comment, and share.

In her article for Psychology Today titled “Social Media and Black Bodies as Entertainment,” Monica T. Williams explains the impacts of “tortured black bodies being paraded across the screen as perverse entertainment,” a trend which is not solely applicable to George Floyd, but also Ahmaud Arbery and Michael Brown––whose photo of his body left uncovered after being shot by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri was widely circulated in 2014. She writes “depictions of police brutality against people of color encourages others to believe that it is normal and fair, and therefore the persecuted must deserve it. Although there is an important role for documentation of abuse to aid in the prosecution of perpetrators, something should be done to limit the publicization of racial violence.”

The circulation of the footage of George Floyd’s murder led to the arrest of all four officers, but over the course of these weeks, police brutality has not stopped. On Friday, June 13, Rayshard Brooks was shot by a police officer at a Wendy’s drive-through in Atlanta, which by nightfall was engulfed in flames. Marquavian Odom, a protest in Atlanta, told CNN “I thought the message was clear, but obviously we’re still not heard.” We should also ask ourselves why we need another video of Black people dying to take profound steps towards dismantling systemic racism.

As students at a Predominately White Institution (PWI), we cannot stop educating ourselves on racism, but it is also important to be aware of the content we are watching and what our motivation is for resharing. I don’t know if I am the person who should be commenting on these trends. On the other hand, I carry with me the responsibility to hold myself accountable and make sure future generations never view violence towards Black people or their deaths as entertainment. We need to be conscious of the content we consume, how we process that information, and what impact our re-sharing may have. This requires introspective work, but we cannot fall into the trap that is white silence.