Photo courtesy of Connecticut College

In a February article, TCV editors evaluated the Connecticut College Mission Statement and concluded that the Conn administration fails to live up to the values they champion and are obligated to put into practice. One of Conn’s main selling points and sources of pride, its Honor Code, is now the object of our scrutiny.

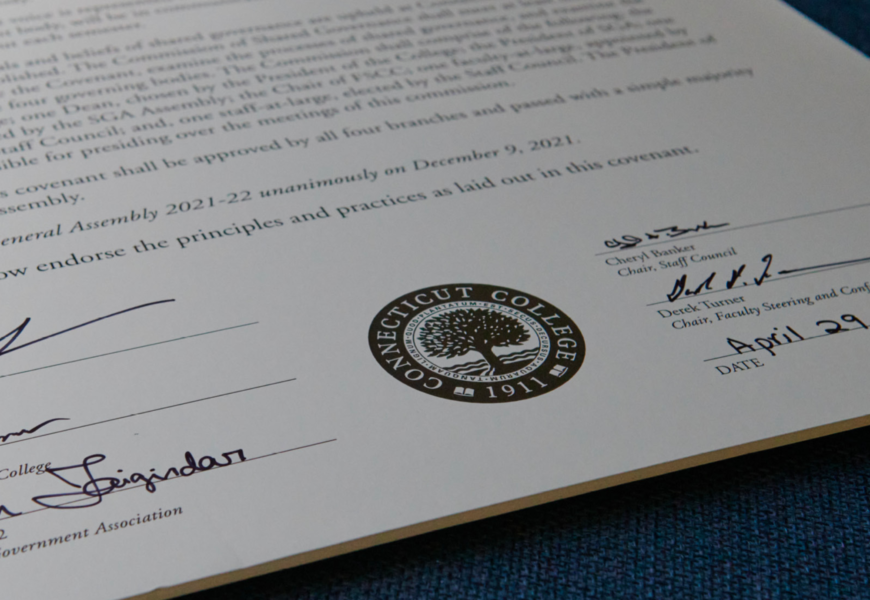

The “about” page on the College website boasts, “Our nearly 100-year-old honor code and commitment to shared governance create a community of trust.” Tour guides are required to speak about the Honor Code on every tour. The website acknowledges that many other colleges and universities have honor codes, but claims that they “are mostly concerned with how you behave when you write a paper or take a test,” while Conn’s Honor Code “emphasizes the collective responsibility we have to each other.” The formulated College website and the strategic Office of Admissions describe the Honor Code one way, but how does the Honor Code actually manifest itself in daily life at Conn, if at all?

“I accept membership into Connecticut College, a community committed to cultural and intellectual diversity,” reads the first sentence of the matriculation pledge each first-year student signs. However, the College’s historic disregard toward marginalized students, faculty, and staff might suggest otherwise. The pledge continues, “I pledge to take responsibility for my beliefs, and to conduct myself with integrity, civility, and the utmost respect for the dignity of all human beings.” Many Conn students, faculty, and staff members follow these principles, yet some administrators have proven that they do not. Katherine Bergeron did not accept full responsibility for her dismissal of Dean Rodmon King’s warning to not hold a fundraising event at the Everglades Club until almost two months after his resignation, in her own resignation announcement. As a member of the College community and governed by the Honor Code, Bergeron owed us integrity, but she did not deliver until her back was against a wall.

“I pledge that my actions will be thoughtful and ethical and that I will do my best to instill a sense of responsibility in those among us who falter,” the pledge concludes. What if “those among us who falter” are the very administrators who preach this Honor Code? Students are encouraged to hold community members accountable but are often censored when they speak out against the College and its administration.

According to the College website, the Honor Code is partly “based on an ancient Athenian oath of citizenship.” The 1922 Student Government Association (SGA) adopted the following oath as part of the Honor Code: “We will never, by any selfish or other unworthy act, dishonor this our College; individually and collectively we will foster her ideals and do our utmost to instill a respect in those among us who fail in their responsibility.” What if we have to dishonor our College in order to make it better? The recent protests brought many of Conn’s ugly truths to the surface, but that was a necessary step toward progress. We cannot blindly foster our College’s ideals if they are flawed. And again, we must remember that administrators are not exempt from “those among us who fail in their responsibility.” Arguably, the Occupy CC protest aligns with the oath’s conclusion of making the College “greater, worthier, and more beautiful” in the future.

Our current Honor Council is made up of four student representatives from each class. Dean Sarah Cardwell is the staff advisor for Honor Council, and there are two Faculty Consultants. Ben Jorgensen-Duffy ‘23, current Honor Council Chair, explained why he initially decided to serve on Honor Council: “I was coming off a lot of frustration from high school about justice in educational institutions and student power so I was eager to dive in as soon as I could.” Honor Council members hold the difficult position of acting as student leaders, simultaneously grappling with the expectation to adhere to the Honor Code and the empathy they feel toward fellow students. Jorgensen-Duffy shared, “I found that over the peak of Covid we were dealing with a lot of cases where it felt like our hands were tied and we were just puppets for the administration instead of serving the students.” The line between true student leaders and “puppets for the administration” is blurry; the Honor Code claims to value student voices, but that is only when students speak in alignment with the administration.

When asked about his experience serving on Honor Council, Kai Listgarten ‘23 wrote, “It has been rewarding…I have agreed and fully, heartedly stood behind 99% of our decisions and sanctioning because we do our due diligence and take our time arguing out the case to see if someone is responsible and if so, what the next steps are.” Honor Council members are somewhat like student judges, hearing out cases and determining the right procedures. However, the Student Handbook states, “Our community standards and our student conduct process…are not based on, nor are they intended to, mirror the rights or procedures in civil or criminal court proceedings.” The Honor Code is based on the ideals of integrity, civility, and respect, which is meant to distinguish it from law. In theory, cases brought to Honor Council should always be assessed with those ideals in mind, but state or federal law can restrict the amount of leeway. Jorgensen-Duffy explained, “There are definitely some policies in the handbook for legal or liability reasons that can feel unjust or excessive, but there is little anyone can do about that and it is understandable that they need to be included to protect the school.”

The Honor Code is a living document that is updated every three years. Jorgensen-Duffy is in the process of editing the Honor Code now, one of the reasons he chose to join and stay on Honor Council. According to him, “the actual Honor Code that we all agree to is decently timeless as it is more value-based, but the policies it encapsulates shift over time as the institution and community change.” For instance, Listgarten commented, “Something that makes the Honor Code slightly out of date is the way academic dishonesty is found and treated. Before, it was much harder to cheat…Now, with ChatGPT, other AI platforms, and professors not knowing how to use Moodle to its fullest extent, a lot of academic dishonesty goes undetected.” With this in mind, we might be seeing a new section in the Student Handbook that addresses plagiarism with AI in the coming years.

It is hard to fully implement such a nuanced set of values/rules in any community, especially a liberal arts college in which the members are taught to question authority and not blindly accept any rules. This creates friction between the administrators who strictly enforce the Honor Code, the Honor Council members who are expected to uphold the Honor Code in their decisions, and the remainder of the students, staff, and faculty, who must adhere to the Honor Code to avoid consequences (in theory). Shared governance would be beneficial if everyone followed the Honor Code, although this is not the reality. The Honor Code might assume that everyone will be truthful because they signed the pledge, but concerns for the lack of accountability beyond the pledge are growing.

Do senior administrators, including the President, sign onto the Honor Code? If not, shouldn’t they? For Connecticut College students, the Honor Code is a lifelong commitment.