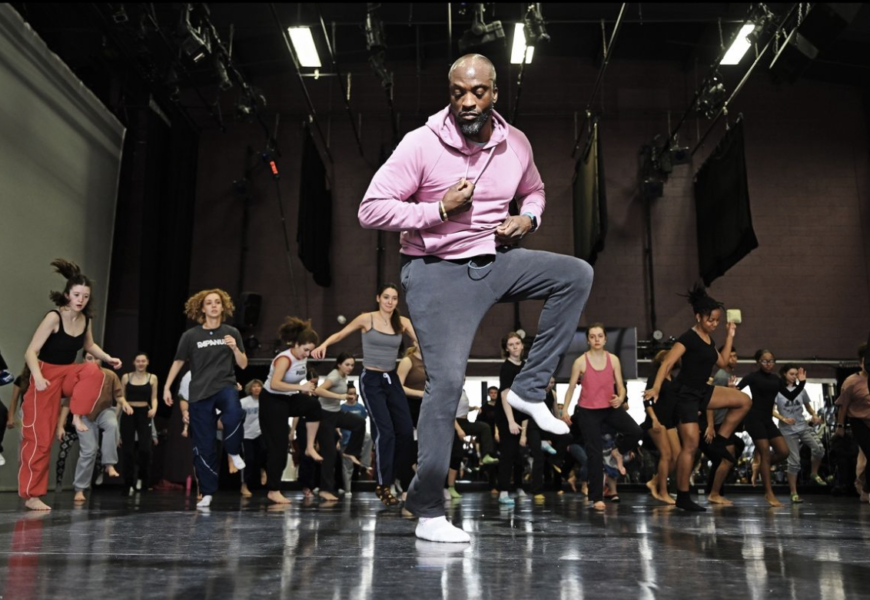

Photo Courtesy of Sean Elliot

Though the cold Connecticut winter drudged onward, artists, students, and faculty from around the country brought the heat to the stages and studios of Connecticut College during the Igniting Emancipatory Possibilities Through African-Diaspora Dance Summit Feb. 8-10. From West African dance to tap, to hip hop, to house dance, a diverse range of African-rooted styles were on full display, raising awareness of the amount of passion and sweat required to master just one of these oft-overlooked dance techniques.

Day one of the conference started off on a high note with the Traditional Contemporary West African Dance Performance Workshop. Instructor Kwame Shaka Opare, a globally renowned dancer, choreographer, and educator, breaks down the technique of West African dance in a way that leaves even the most inexperienced dancers with a basic understanding of the style. Despite his long list of accolades, Opare is clearly invested in the success of each student he interacts with. At one point, he went so far as to step in to assist struggling students in a different instructor’s Summit class, remaining patient and encouraging as the students attempted to follow his instructions. Opare received a long bout of applause at the end of the Traditional Contemporary West African Dance Performance Workshop, a celebration of the skill and positivity this generous individual brought to the studio.

A few short hours later, the mere presence of guest artist Ronald K. Brown filled the room with awe as Summit participants were given a taste of Evidence Dance Company’s signature choreography. Based in the traditional West African movement, Evidence is known for its groundbreaking blend of Western and West African dance techniques, and has been featured at many of the most prestigious dance venues in the United States. Many of the arm motions students were taught extended upward to represent a reach to the ancestors above. Though the choreography was taught rather quickly, the balance of layered, rhythmic music and dynamic movements made Brown’s step sequence fairly easy to pick up on—and highly satisfying to dance.

“How do you spell arms? B-A-C-K,” says Allana Scudder. It’s day two and a packed studio of students are learning house dance, a freestyle form closely related to hip-hop. Scudder starts the class off with a couple of simple steps, gradually adding on and changing formations until participants split into halves and turn to face one another. The energy is palpable as each side trades off performing the steps, whooping and hollering for friends and strangers alike. Smiles and flushed cheeks could be seen all around as the session came to a close, marking the end of an hour filled with fun.

Just a few hours earlier, Connecticut College adjunct professor Alexis Robbin’s presentation on the importance of tap dance in higher education dug deep into the roots of the style, boldly confronting the racism that has led to the marginalization of this form that continues even today. Speaking out to a room full of students and faculty alike, Robbins breaks down how tap is still de-emphasized and disparaged in dance spaces across the country, pointing out how most studios lack the wood floors necessary to properly “play” the sounds of the tap shoes and the lack of tap classes at many colleges across the country. For reference, Connecticut College does not offer more than one level of tap to students. In Robbin’s own words, “Living freely means wood floors. Living freely means [tap] having the same seat at the table.”

Day three of the summit wrapped up with another full day of classes (one of which involved a hilarious scene of students attempting to jump backward in a plank position across the floor), as well as a phenomenal keynote performance and Q&A session by Ronald K. Brown Evidence, where Dance Department professor Shani Collins made a guest appearance. A former dancer with Ronald K. Brown Evidence Company, Collins wowed audiences with her technique and artistry, once again reminding the Connecticut College community how fortunate it is to have such experienced professionals as professors.

It was the efforts of these same professors that made the Igniting Emancipatory Possibilities Through Africa-Diaspora Dance Summit possible. As the recipients of this year’s annual Dayton Artist-in-Residence Conference funding, the Connecticut College Dance Department was determined to host an event celebrating dance as a force for good. “The Dayton has always been about how we can draw our community together and celebrate Afro-Diaspora forms,” says Collins. According to Professor Collins, the department spent months upon months building an event geared towards “drawing people from the Northeast and galvanizing and honoring teachers, scholars, and artists that do this work, particularly inside of Predominantly White Institutions.” Dance department professor Rosemarie Roberts concurred with this statement, writing in an email that “we understood that we were not alone in terms of the challenges and possibilities of teaching Afro-Diaspora Dance in small liberal arts settings, which are predominantly white. Using the Dayton Artist-in-Residence Funding seemed like a great way to continue to support the Department’s efforts.”

Connecticut College is one of a limited number of institutions to offer techniques beyond just ballet and modern, and many students come to the department with little knowledge of any non-Western dance styles. When individually asked whether they would consider Conn to be a leader in dance technique diversity, both Collins and Roberts responded with a resounding yes. “I would say that continuing to work through all the institutional roadblocks in centering and integrating Afro-Diaspora dance in college dance as well as continuing the work with other institutions is a powerful initiative and expression of leadership. In most college/university dance departments, non-western forms are taught as electives, rather than as part of core curriculum,” comments Roberts. “We have the practice of it (in terms of the physical practice), but also the theoretical, the historical, the cultural studies of it all. We’re a leader because of the makeup [of the curriculum],” adds Collins.

Ultimately, it seems Conn’s progressive outlook on dance has paid off. “I used to get a lot of pushback. You know, when you’re teaching something, sometimes it feels like ebb and flow, but I feel like we’ve been on this momentum where it is inline and relevant to you all, so the [student] attitudes are great,” shares Collins. Roberts also believes student frames of mind have improved over the years, expressing that “I’ve seen a shift over the years in our dance majors who take Afro-Diasporic classes. Whereas, those with studio training were most concerned that taking Afro-Diasporic dance would adversely affect their ballet and modern training, now students tend to be more open to the possibility of broadening and deepening their study of dance.”

Though this was not the first or only African-Diaspora Dance Summit in the Northeast, Igniting Emancipatory Possibilities Through African-Diaspora Dance proved to be a unique and personal experience for all involved—and will be remembered as such. As summed up by Collins, “It’s so affirming in the work that I’m doing, and the work that I’ve been doing sometimes by myself, so it’s amazing to have the support and see it reflected in the curriculum, to see it reflected in the students. It gives me a little bit more wind beneath my wings to continue to do the work when I’m seeing colleagues who are also in situations where they may be the only black person in the department or one of five in the whole school, so to be able to come together is really powerful.”