Courtesy of Lee Howard

When you’re hanging out with your friends in your dorm room, you never expect to start a social movement – but that is exactly what happened in the basement of Larrabee House in 1972.

In 1971, the federal voting age was lowered from 21 to 18. During the Vietnam War young people became more politically active and invested in what was going on, so there was a strong desire to vote. Many college towns saw that as a potential problem. In a lot of these cities, the students made up a significant portion of the population, and had the potential to change the results of an election. That is why many places, including New London, struck college students from the voter rolls. After 146 Connecticut College students registered to vote in New London, they were disqualified as voters, on the grounds that they were not actual residents of the city.

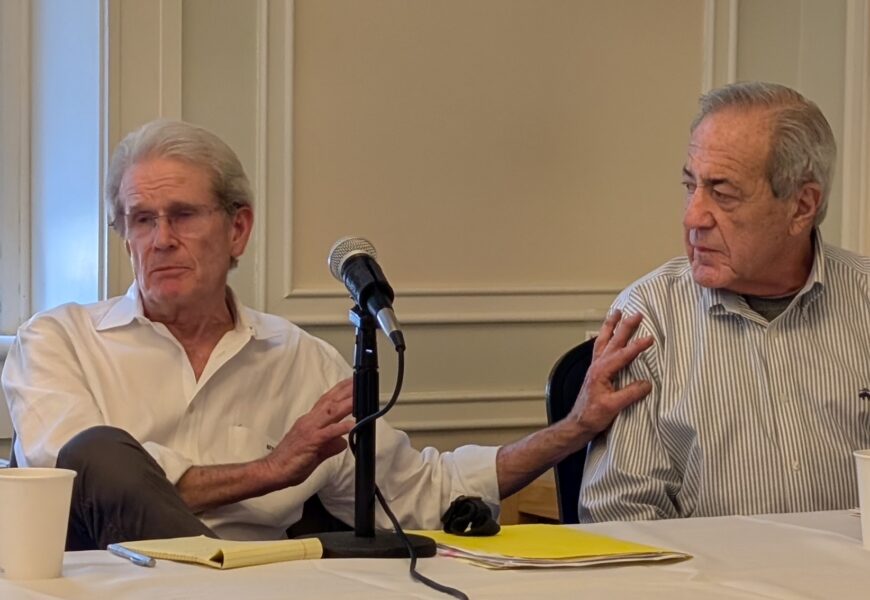

On April 24, the Government and International Relations Department held a panel entitled, “Student Activism Past and Present: The Conn 146 and the Landmark 1972 Class Action Lawsuit,” moderated by Dr. Daniel Moak, associate professor of Government. There, Alec Farley ‘75 and Jay Levin ‘73 discussed their experiences and gave advice to the current generation of college students.

“We all felt, when we came to this school, all 477 Class of 1975 students, we felt a certain mission here, that transitioned Connecticut College,” said Farley. “You just do things. Stuff happens and you connect. And you look for the opportunities to find and to speak your mind.”

Farley was in the process of founding WCNI, the college radio station, with help from lawyer Thomas Wilson, when his voter registration in New London was rejected. Farley complained to Wilson, who suggested that he fight back. Eventually, he became the lead plaintiff in a class action lawsuit composed of 146 Connecticut College students, to fight against their bar from voting.

They eventually won the court case, a major achievement for expanding voting rights. Meanwhile, similar cases took place across the country, including in Worcester, MA and Mercer Country, NJ.

Levin explained that before the case even took place, there was a propaganda movement in New London to rile people up against Conn students voting in town. Afterwards, the Democrats of New London realized how valuable the college students would actually be to their mission, and accepted them, when a large majority registered with the party.

Both men stressed starting small and seeing where you end up, which is how they achieved success in securing their right to vote in New London. Through talking to their neighbors and friends, they built a cohort of up to 146 concerned students. Farley noted: “the import of it is that a little thing that you do can have a ripple effect that you don’t realize what it does and it causes change and it’s powerful.”

Farley compared his experience starting the Conn hockey team to starting a social movement, saying “what’s important about that is that I got a couple of other people who had the same interests as I had and we got together and we helped each other play hockey and it grew to a full team.”

“On the campus it was relatively easy to organize because it’s dorm to dorm, there were digestible chunks of people you could sit with,” explained Levin. “When I look at the list of plaintiffs there’s a heck of a lot of them who were from our dorm… so you could say the trouble started there,” he said, of course referring to Larrabee.

Levin was very politically active during his time at Conn and after. Taking part in this case was the first time he really interacted with the broader New London community, which he ended up becoming involved with throughout his life. He participated in several election campaigns in the area, including that of Ernest Kidd, the first African American man elected to the New London City Council. Levin went on to serve as Mayor of New London for several years, and was a lawyer for both the county and private firms.

Conn can trace its long history of political action to 1911, when it was originally founded as an all-women’s school after a neighboring institution stopped admitting women entirely. The school became co-educational in 1969, so the early 1970s was a major period for social change on campus. Farley said this was a time of “major transition and there was a six year or seven year period of that transition, and our class was right in the middle of it. And it was a tremendous time because we could do so much and we were supported by the school.”

The case also has long-lasting impacts, as the important precedent helped shape Connecticut state residency requirements. It was even cited in a 2020 New York State case surrounding voting rights and residency requirements. Out-of-state college students can still use 270 Mohegan Ave as their voting address, over fifty years later. This kind of action, starting small to make monumental change, can serve as inspiration for generations of students moving forward.