As uprisings in the Middle East continue to rage on in countries like Yemen and Syria, the Arab world is still very much on the minds of the international community. In the last year alone, we have borne witness to the toppling of decades-long dictatorships in Tunisia, Egypt and, most recently, Libya. A new era is unfolding in the region, and the epoch of despotism is rapidly waning. But how did these governments last for so long in the first place? One method of control was propaganda.

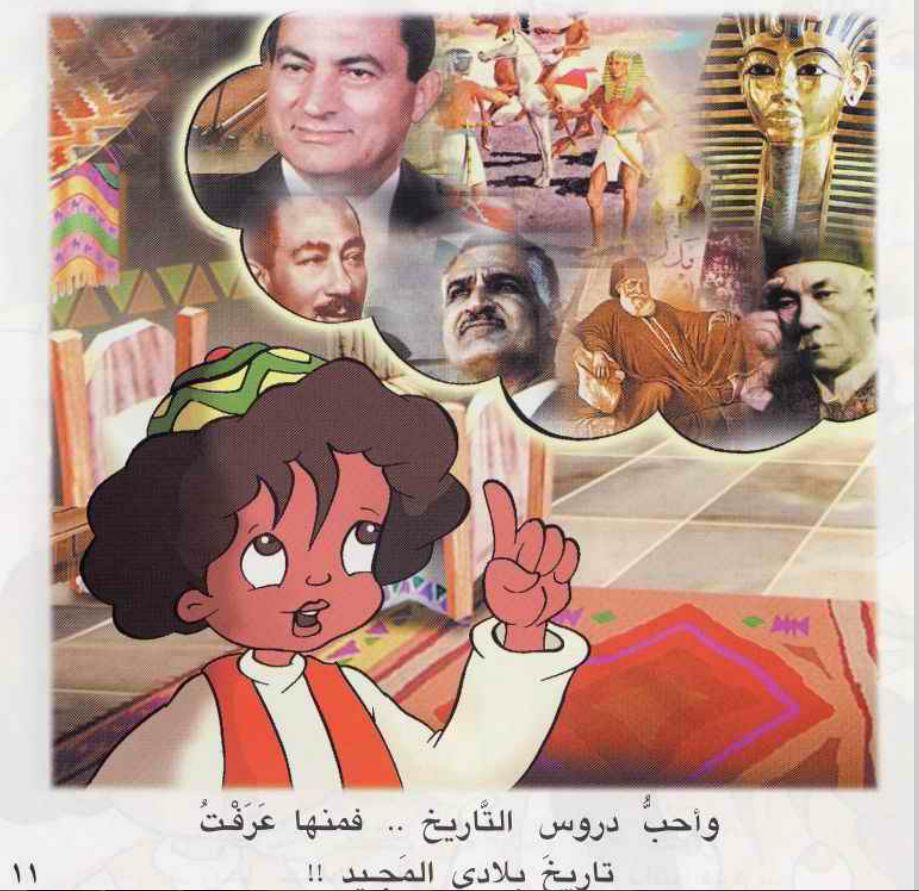

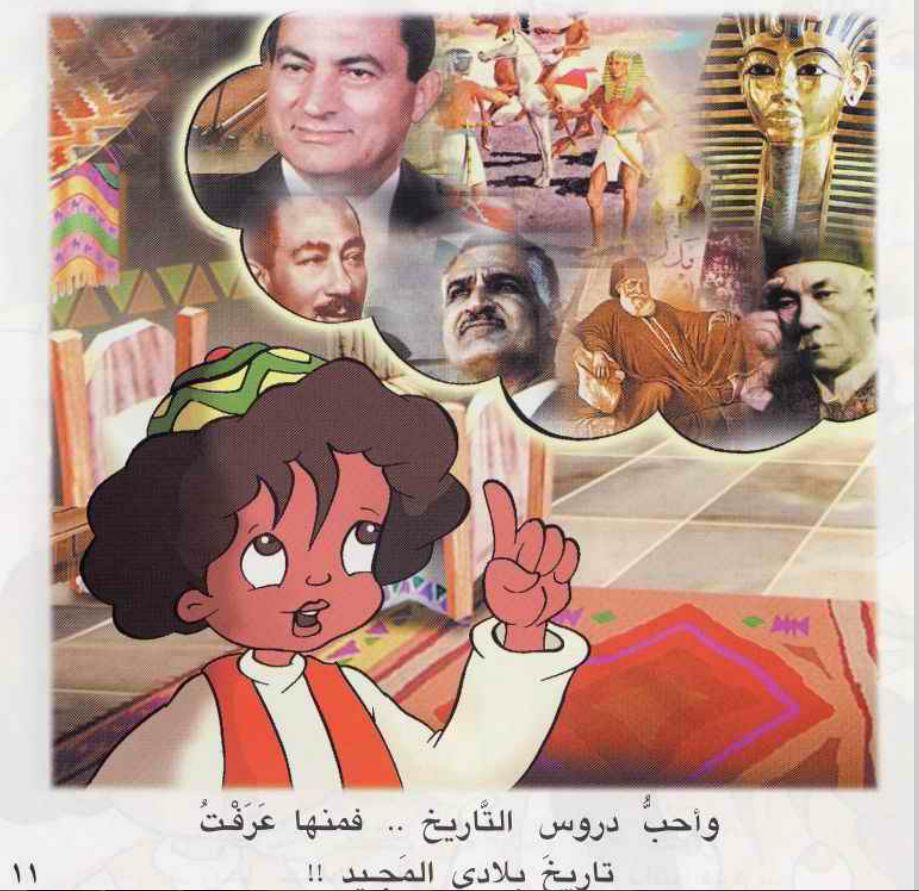

Muhammad Masud, a PhD candidate at the University of Illinois, spoke to an eager crowd of professors and students in the Charles Chu Room about indoctrination and propaganda in Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt. His research focuses on the role children’s books played in effectively brainwashing the youth of Egypt from their adolescence, particularly those books published under the Reading for All campaign of Suzanne Mubarak, then-First Lady of Egypt.

Masud began his lecture by describing the Reading For All Festival, an initiative launched in 1991 by Mrs. Mubarak that attempted to provide books to the underprivileged classes of Egypt as well as to persuade children and their families to use libraries. Funded directly by the Egyptian government, the initiative was in spreading enthusiasm for reading all across the country. In fact, from 1991 to 1992, the number of libraries participating in the program increased almost tenfold, and that number continued to increase until 2010.

At this point, Masud played a commercial for the program to the audience that showed Egyptian families sharing tender moments with books, children nuzzling up on comfortable chairs and smiling while their parents read to them. The music was soft and the mood was warm. “Notice the high production values, the quality,” said Masud. Clearly, a lot of money was spent on trying to sell this program to the Egyptian population. Masud noted that many Egyptians criticized the program as unnecessary or superfluous, inquiring as to why there was a Reading For All movement when there wasn’t even water or bread for the whole population.

Masud went on to briefly summarize six children’s books published under Reading For All. “In this series, the stories are constructed in a way that reflects the adult’s perspective of what is good or bad, or right or wrong. The adult point of view that the series adopts is, of course, the same as that of the state.” Since the adults reading to their children had already been indoctrinated by the state, Egyptian families were further training their children to act in accordance with the government by reading these books and propagating their messages.

The books had little to no story line to speak of, and were extremely simplistic in their approach. Topics covered ranged from classroom obedience to Egypt’s treaty with Israel. This rudimentary style of writing was a result of Mubarak’s regime vastly underestimating the critical thinking ability of Egypt’s youth while being fully aware that proselytizing must be introduced during childhood in order to breed “normal” and “obedient” citizens.

This combination of tainted children’s books and the trained adult mouthpiece for them was the capstone of Masud’s talk. “This formula has children’s literature accomplish a cleansing effect by offering a world of normalization that denies the existence of any oppression. It says, ‘this is who we are; this is how our world looks like and that is how we must act.’ There becomes no other way of existence.” Yet in hindsight, the people of Egypt knew that there was another possible existence and fought in the streets for it, which made the talk all the more fascinating.

All of the information presented at this lecture was a result of Masud’s independent research on the topic, a theme he felt was too often ignored while studying despotism in the Middle East. Paige Cowie ’12, an International Relations major in the crowd, noted, “It was an interesting insight into a seemingly harmless and positive reading program in Egypt that actually had a much larger agenda attached to it.” Claire Brennan ’13 said, “The lecture made me reconsider all of my notions about the Arab Spring and how propagandizing is bred in authoritarian regimes.”

Masud’s talk demonstrated the need to look backward while simultaneously looking forward in analyzing the Arab Spring to fully comprehend events on the ground. Although the Mubarak regime in Egypt was thinking they were breeding obedience and a trained population, the reality was quite different – proselytizing can only influence citizens, not mold them. •