In December of 2014, over forty people contracted measles in an outbreak after visiting Disneyland in Anaheim, California. The affected individuals are reported to have contracted the disease via an unvaccinated woman, either through direct or indirect contact. While this specific incident captured national and international spotlight, it also focused media attention on other cases of measles around the country, which now total 155. The current measles outbreaks in 16 states have generated intense debate over the efficacy of vaccinations and public health regulations, not just in the United States but also internationally.

The measles is a highly contagious viral disease, but cases have steadily decreased since the invention of a vaccination over fifty years ago. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), prior to 1980, when widespread vaccination became the norm, measles resulted in 2.6 million deaths per year worldwide. Invented in 1963, the MMR vaccine treats measles, mumps and rubella and is administered to children between the ages of 12 and 15 months. By WHO’s estimates, approximately 84% of the world’s children receive the measles vaccination, which between 2000 and 2013 alone, resulted in the prevention of 15.6 million measles related deaths worldwide. Indeed, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) reports that in 2000, the measles was eliminated in the United States, which meant that the disease was completely absent for over twelve months. Incredibly effective, the vaccine is also relatively inexpensive at one dollar per dose – a cost that is covered by most insurance providers, including the Affordable Care Act.

Outside of the United States the measles is still a common disease, with cases reported in Europe, Asia, Australia and Africa each year. The disease is particularly common in countries with lower per-capita incomes and weak healthcare systems. Yet, the fact that measles cases are occurring in the United States, where preventative measures are readily available but not always taken, raises the question as to why people remain unvaccinated.

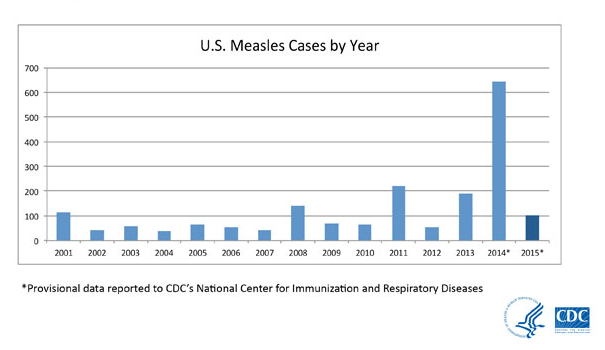

Many people who choose not to immunize their children do so for religious or philosophical reasons. In the last decade, the United States has experienced measles outbreaks in 2008, 2011, 2013 and 2014. During the 2014 outbreak, 644 reported cases occurred in Ohio, where there is a prevalent Amish community, which chooses to abstain from vaccinations as part of their religious and cultural beliefs. Although religious abstainers are the majority of the people who remain unvaccinated, it has been the “Anti-Vaxxer” movement that has captured the attention of the national news syndicate. The Anti-Vaccination movement consists largely of parents who choose to abstain from immunizing their children because they believe vaccinations are unsafe or pose significant health risks to their children.

One of the most famous voices of the movement is Jenny McCarthy, the actress and TV personality who has repeatedly asserted her belief that vaccines lead to autism, based on her own experience with her autistic son. This theory – propagated by Andrew Wakefield, who Great Britain stripped of his medical license in 2010 – has widely been discredited within the medical community, but some doctors continue to support these ideas. As Virginia Hughes, the Buzzfeed News Science Editor reported in early February, the reason her own parents decided against vaccination was because of advice they received from the medical professionals they came into contact with in their rural and conservative Michigan community.

Although people are entitled to make their own decisions regarding their children’s health, the prevalence of the measles presents a major public health issue. Dr. Kate O’Brien, the executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who was recently interviewed by BuzzFeed, asserted that for every one person infected with the measles, the disease will spread to another 12 to 15 people. Because the disease spreads quickly through mucus membranes – coughing or sneezing – high rates of immunization are responsible for the prevention of the disease, particularly to people who are unable to be vaccinated.

In late January, Carl Krawitt, a concerned father, contacted the superintendent of his Marin County school district requesting that all unvaccinated children be mandated to stay home out of concern for the health of his son, a cancer patient whose immune system was weakened by chemotherapy. Because Krawitt’s son’s immune system is compromised, his health is at an incredible risk if he comes into contact with someone who is not vaccinated. In addition to Krawitt’s son, people who are allergic to the MMR vaccine, are otherwise immunocompromised or are unable to receive the vaccine due to age, are extremely susceptible.

Their safety is guaranteed by the prevalence of vaccinated people, a phenomenon called the “herd immunity.” If the majority of people are vaccinated against measles, the disease is unlikely to spread and the community’s immunity protects those who cannot be vaccinated. As more and more parents are opting not to vaccinate their children, the herd immunity weakens. Because the measles is so contagious, the decrease in vaccinations will generate more cases.

Other people who choose not to vaccinate their children report that their decision stems from their belief that the measles is less threatening than the vaccine. Although the vaccine does risk side effects, including fever or mild rash, some people can experience a serious allergic reaction, though that is incredibly rare.

Both the WHO and the CDC report that the vaccine is safe but that the disease is dangerous if contracted. Measles symptoms include high fever, cough, sneezing, watery eyes, mouth sores, sensitivity to light and a painful rash that spreads throughout the body. Symptoms can last for 10-12 days, and in severe cases can also lead to severe ear infections that cause deafness, diarrhea, seizures, pneumonia and swelling of the brain that can cause death.

These complications led to the death of Olivia Dahl, daughter of famed writer Roald Dahl, whose letter about the necessity for the measles vaccine resurfaced during the first week of February. Dahl’s daughter died of measles at the age of seven in 1962, (just a year) before the vaccine was introduced. As a result, Dahl has campaigned tirelessly for the vaccine to be implemented and widely accessible.

The measles continues to pose a serious public health issue, not just in the United States, but also internationally. Although the number of reported cases has reached 155 in the United States since December, on Feb 7, the Washington Post reported that Germany is also currently experiencing a major outbreak.

In January, 254 new cases of measles emerged, primarily in Berlin and largely due to a failure to vaccinate. Although Germany maintains a 97% vaccination rate, over one third of these cases were vaccinated after the recommended timeline or failed to receive a second dose of the vaccine, which both WHO and the CDC recommend for increased effectiveness.

NBC News also reports the current outbreak in Germany in relationship to wider historical trends across Europe. Like the United States, most Europeans have access to MMR vaccines, but in 2014 the continent still saw 3,840 cases, with Italy alone reporting 1,921 of the total cases. In 2013, 10,000 cases of measles were reported in Europe, and in France, 23,000 cases have been seen in the past decade. Many of these cases emerged as result of decreasing vaccination rates, which differed from country to country. A number of reported cases originated from Roma or Traveler populations and in poor or otherwise isolated groups who slip through the government-regulated healthcare systems.

As the measles continues to spread through Europe and the United States, the new cases continue to demonstrate what recent history has shown: a clear link between failure to vaccinate against the measles and an increase in measles outbreaks. Vaccination alone does not eliminate a disease; people must be willing to take it. •