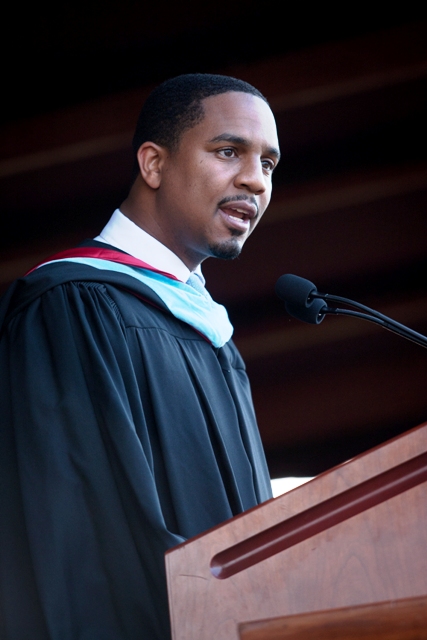

To the College’s fast growing collection of administrative positions, there has been a high profile and long-awaited addition: the Dean of Institutional Equity and Inclusion (DIEI). Our first permanent DIEI, John McKnight, joined us this July from Lafayette College, where he served as the Dean of Intercultural Development.

“People have been really excited about the position, to have someone permanent in higher admin doing this work,” McKnight told The College Voice in an interview in late August. Much is expected from McKnight’s position, which has been the center of heated debates, discussions, and demands for at least the past two years, if not the past few decades. The position was newly articulated in the search that began in February 2015, and has gone through more than its fair share of trouble. The search, having been paused due to popular protest in spring 2015, restarted in June 2015 and failed twice in the early months of 2016, finally went through a third pool of campus visits to select the DIEI, over a year after the search first began and two years after the College’s previous senior diversity officer left. In the meantime, the position, first held by a team of interims cobbled together hastily by the president following popular protest and demands, was held by an interim dean who was asked to stay on the job for a full semester more than he had initially signed up for. The interim DIEI’s term finally ended with an occupation of his office and the Office of the President in spring 2016 by a large group of student protestors.

In spring 2015, the DIEI was hoped to bring “Inclusive Excellence” to Conn. By the time all the iterations of the search have unfolded, “inclusive excellence” has given way to “equity, inclusion, and full participation,” in recognition of the fact that Conn has too much to do before aiming for inclusive excellence. The job is now in the hands of McKnight.

“In America, diversity is big business,” opens McKnight’s PhD dissertation, a critical insight of the sort that one would not necessarily expect from someone in the business. This is one of the things that distinguishes McKnight from other administrators: he is able to still name the problems of higher education while being inside it. This is one of the main things he brought up as a challenge of his job: “How do you critique an institution while existing within it and trying to make the best of it, trying to make sure people have the opportunity to feel at home?” For McKnight, the challenge is to be a critic and caretaker at the same time, to challenge the privilege that can be “really baked into these institutions” and call it out, while also building a sense of community for the people currently at the institution.

His previous position, Dean of Intercultural Development, focused his energies on the student experience, programming, and advocacy, while the DIEI position charges McKnight with thinking about equity at the institution as a whole, a task that requires him to work with faculty, staff, and students. He maintains that creating a dialogue with all members of the college is crucial to changing the campus climate. When asked what work his office has already started doing over the summer to achieve this goal, McKnight mentioned that training for staff and various administrative offices that has taken place to ensure that everyone has developed language to talk about equity and inclusion and understand how their work on campus relates to the work of the DIEI office.

His office has also been working on strengthening policies and procedures; for example, finalizing the bias protocol policy for students, which was included in the student handbook this fall. McKnight’s approach towards policies like bias protocol is that they are a pragmatic necessity but not the main way to do diversity work. “Policies and procedures need to be there for us to fall back on,” he said, “but I want to move away from using the bias policy; for me things have gone awry if we are using it as often. I like to be more proactive in my approach.” The protocol is also too narrow in scope to serve as the primary site of change. McKnight explained: “I would like to get us out of that space where everything is reported as bias. Some things may not rise to that threshold. It might be terrible, offensive, hurtful, rude, unprofessional, but “bias” actually does come from a legal definition of what it means to target someone based on their membership in a Protected Category, and if it falls short of that, it doesn’t mean we are not going to be interested in addressing it, we will, but the bias protocol is not always the place for it.”

But besides mentioning his interest in getting to know people on campus on a personal basis, McKnight was less clear on the strategy of the DIEI office for addressing incidents that do not constitute legal bias but violate an expected professionalism or code of conduct. Instead, he shifted the conversation from the reports themselves to the climate that produces them. “Students who carry identities that are or that they experience as marginalized tend to have the loudest voices around certain issues. I understand it; I was one of those. But I want to hear from the huge silent middle of students who may be underinformed, not thinking about these issues. I worry about those students who are having their college experience influenced by students on either end. I would like my office to spend less time on the groups on the extremes of each issue, and more time inviting silent middle into conversation.” He established clearly his interest not in responding to incidents but in creating robust engagement with controversial issues, an approach that is sure to be a good fit to Conn, where the majority of the student body abstains from conversations about difference and power. At the same time, though, McKnight’s answer leaves me wondering what exactly the DIEI office will do to address the day to day problems of marginalized members of the community that do not qualify as legal bias.

One of the ways that McKnight’s office could reach the “silent middle” as well as the extreme ends of various issues would be through the curriculum. When I brought up the question of the curriculum, McKnight expressed excitement about Connections but clarified that “this is not me jumping on board and drinking the kool-aid,” saying that how Connections manifests will have to be closely monitored by his office along with the DoF and others to make sure that course offerings are diversified and address issues of equity and inclusion. McKnight was optimistic about what he had seen with regards to faculty taking initiative under Connections to develop such critical coursework. “We might not see some provocative new course titles for a year or two as they are letting ideas germinate,” McKnight stressed. “We should give it a chance and see how creative and adaptive faculty will be in terms of what they will offer.” It remains to be seen how much say the DIEI office will have over curricular offerings if in a few years, they do not meet McKnight’s hopes.

Even though the DIEI is cast as an institution-wide position, the main initiatives of the DIEI seem to target staff and students. This is not surprising since faculty are typically exempt from much management by the College outside of the Dean of Faculty’s office and their own elected bodies such as FSCC. This would explain why a major demand with regards to the bias protocol, that it address faculty/student biases as well as student/student ones, has been left unfulfilled. It also explains why the success of Connections at educating students about power and difference ultimately depends on faculty initiative instead of any mandates coming from the DIEI’s office. When asked about these thorny issues of faculty autonomy, McKnight largely acquiesced that his job was not to manage faculty but made it clear that this would not mean that he would not make his thoughts heard if faculty members undermined the efforts of his office in building a united community (although he thinks this is unlikely to happen). “Just because I say it doesn’t mean you have to do anything different,” he clarified, “but I am not going to not say it.”

Finally, our conversation turned to the events of May 2016, when a group of students occupied the office of the interim DIEI at the time, David Canton, for the final week of the spring semester. When asked if he knew the circumstances of the occupation, McKnight expressed reservations. He said that there was much for him to understand about the circumstances of the occupation, including why it was that the DIEI office was chosen as the site to protest. “I want people to understand that this is part of my job. If you are choosing to protest the administration, this is one of the places, historically, and around the country, that tries to align itself with the mission and objectives of most social movements on campus. If this office is being held up as an example of the oppressor, then we are all in trouble.” And he added: “There’s no reason to think it is over.”

McKnight expressed interest in speaking to the students involved in the occupation in order to work with them. “I have a seat at the right table, being a senior admin,” he said. “I have an opportunity to be reflective of peoples concerns, if I know what the concerns are, and if they are reflective of the two goals I mentioned before: to move the institution forward in positive ways and to build community.”

The tricky balance of the DIEI’s position – as both a member of Conn’s senior administration and as someone who was hired to challenge the administration and the College, as both critic and caretaker of the power dynamics in place – was apparent in this discussion. Even as he emphasized that his office was a product of student activism over many decades, and was supposed to be representative of voices of marginalized people on campus, he also said that it was “hard for [him] not to be in solidarity with” the interim DIEI and his team in the context of the occupation, since they are people that meant well. Even as he called being a senior administrator and having access to closed-door conversations “his form of protest,” he still emphasized that students cannot fully know the vantage point of those who run institutions like Conn when they protest these institutions. He brought up how, when he was an undergraduate at the University of Florida, he went on the record saying: “the entire University of Florida is racist.” If he could talk to his 19-year-old self now, he would say “Yes, you are right to feel what you feel, yes you’ve experienced racism, felt like you’ve had to represent your race, felt underprivileged, and no, the school wasn’t designed for you, they didn’t have you in mind.” Looking back at his thoughts then, he now thinks that “of course the University of Florida is racist, every institution is racist, we live in a racialized society where everything was founded on racism,” but at the same time says that experience has helped him understand how institutions work better than he did when he made that critique as a young activist. This leaves us wondering how exactly McKnight will understand students at Conn who critique the institution and its workings – are they justified in their feelings and deserving of the change they are demanding, or should they try to “lift up from their vantage point” and realize that the institution’s workings are too complex to aim simplistic critiques at it? There is some delicate balance between these viewpoints that McKnight aims to achieve. It remains to be seen whether he will be able to establish that balance here at Conn.

If his background is any indication, McKnight has never shied away from a challenge such as this one. This is evident, for example, from the subject of his dissertation, which is titled “Brothers in the Struggle: A Phenomenological Study of White Male College Student Development as Social Justice Allies.” As the title suggests, McKnight was interested in exploring the formation of white male allies. His dissertation focused on the transformative capacities in the most difficult constituencies when it comes to racial justice work, an interest which very much mirrors his interest in doing diversity work at pre-dominantly white, small liberal arts colleges.”I sometimes think I am a glutton for punishment,” McKnight jokingly said, agreeing with this assessment. “It [at small liberal arts colleges] is a very challenging environment. Colleges like Lafayette and Conn have a longstanding history of being very exclusive in their policies and practices. The challenge for all of us is to move these institutions forward and bring about systemic changes that will enable individuals to relate better on the interpersonal level.” Given the vexed history of this work at these institutions in general and Conn in particular, many will be keenly watching to see how McKnight’s office and division take on this challenge in the time to come. •