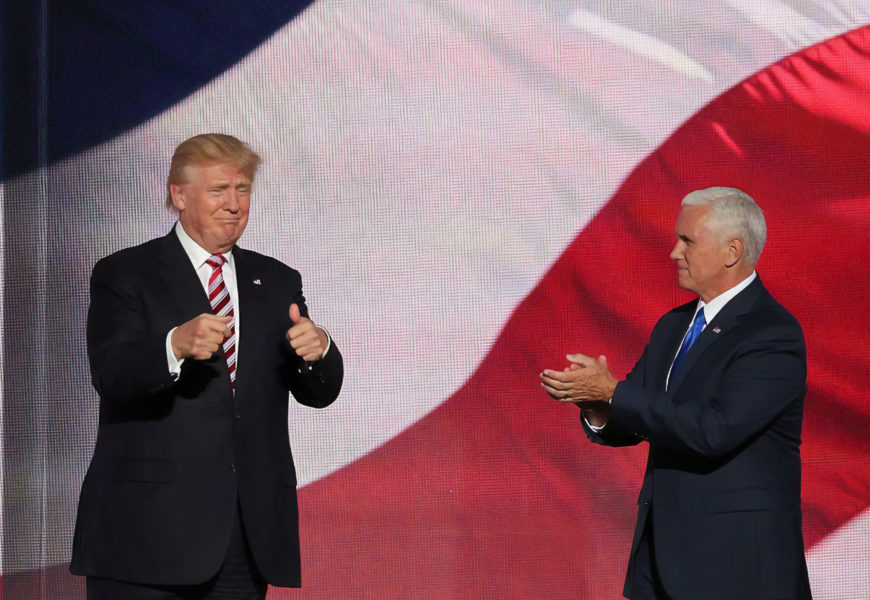

President Donald Trump with VP Mike Pence. Photo courtesy of History in HD on Unsplash.

For any observer of this year’s presidential election, it is nearly impossible to ignore the constant barrage of the Republican nominee’s offensive comments, personal attacks and outrageous scandals in the media. Since Donald Trump declared his candidacy in June of last year, he has likened Mexican immigrants to rapists and criminals, proposed a ban on all Muslim immigration to the United States, mocked a reporter for his disability, personally attacked the spouses of his political opponents, incited violence at his rallies, suggested the assassination of Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton and refused to accept the result of the democratic process if he is not declared the winner of the election. Additionally, increased media scrutiny throughout the duration of Trump’s campaign has revealed that he previously questioned the legitimacy of President Obama’s birthright citizenship, was sued by the Department of Justice for housing discrimination, scammed $40 million from 7,000 individuals enrolled in Trump University, refused to pay contract workers hundreds of thousands of dollars, used a tax loophole to avoid paying any federal income tax for eighteen years and bragged about sexually assaulting women.

It does not seem unfair to assume that any one of these scandals on its own might make a rational voter think twice before voting for a presidential candidate and that the collective sum of all of these scandals might certainly dissuade a large portion of the electorate. Perhaps not too surprisingly then, many voters have been dissuaded from supporting Trump’s candidacy as a result of the proliferation of these scandals throughout the duration of the presidential campaign — including many voters from Trump’s own party. A sample of leading Republican politicians reveals this trend: 2012 Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney has actively opposed Trump’s candidacy since the primaries, 2008 Republican presidential nominee and U.S. Senator John McCain recently withdrew his endorsement of Trump, former Republican U.S. President George W. Bush has refused to endorse Trump’s candidacy or even weigh in on the election, and a few months ago former Republican U.S. President George H. W. Bush revealed that he will be casting his ballot for Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton.

Indeed, Trump’s unconventional and continually controversial candidacy has caused many lifelong Republicans to abandon their party’s presidential nomination this year — with some turning to former Republican Governor of New Mexico Gary Johnson on the Libertarian ticket, some to conservative independent Evan McMullin, and some even to Trump’s principal rival, Hillary Clinton. Yet, even with the scandals, the opposition he faces from within his own party, and unfavorability ratings that reached 62% this September, Trump has maintained consistent national support from between 30 and 40% of the electorate. Trump himself took notice of this phenomenon in January of this year when he bragged: “And you know what else they say about my people? The polls! They say I have the most loyal people – did you ever see that? Where I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose any voters, okay?” And he’s probably right. Despite every news cycle that broadcasts Trump’s latest controversial comments, a particular bloc of white working class voters stays loyal to this candidate. These voters are not fazed when Republican elites publicly criticize their nominee’s character and temperament. They are not persuaded by talk show hosts and anchormen that relay the dangerous implications of Trump’s latest gaffe. They do not reconsider their vote when Trump’s comments are labelled sexist, racist or otherwise bigoted. To them, the media has a well-known liberal bias and Trump simply tells it like it is.

So who are these voters? And why are they not swayed as easily as other Republicans and independents? Since Trump’s presidential campaign exploded onto the national scene in 2015, many journalists, political pundits and politicians have attempted to make sense of his 21st century brand of right-wing populism which appeals so strongly to a large segment of the country’s white working class. Hillary Clinton, in a speech given in September, summarized the media’s consensus on these voters when she said that “you can put half of Trump supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables.” Much has been written on the subject of racism and xenophobia as it pertains to Trump’s supporters in this election and the dominant narrative seems to analyze prejudice among these voters as separate and distinct from their economic situation. However, applying historical context to Trump’s popularity with white working class voters today reveals that racism and xenophobia among poor whites in America has long been tied to the economic anxieties of poor whites.

To explain the rise of Donald Trump and the appeal of his message to the white working class, it is first necessary to understand that his brand of right-wing populism is not new to American politics. In the 2016 presidential election, Trump has made the issue of illegal immigration the center of his campaign. On the campaign trail, Trump has maintained his claim that undocumented immigrants are stealing American jobs and receiving far more in “welfare benefits” than legal American citizens. He has implied that undocumented immigrants are consequently the root cause of the decline of the American Dream and diminishing economic prosperity in the United States. To ‘Make America Great Again,’ Trump resolves to deport roughly ten million undocumented immigrants already living in the United States, constitutionally redefine the meaning of birthright citizenship and build an “impenetrable physical wall on the southern border” with Mexico to prevent any further illegal immigration.

Faulting people of color for the economic misfortunes of whites is a trend that has existed in the United States for centuries and can be traced back to as early as seventeenth century colonial Virginia. Americans today might be surprised to learn that in Jamestown in 1619 African slaves and indentured Europeans arrived to the colony with essentially the same social status. The landowning Virginia elites needed labor to build their colony and work their plantations and they found that both enslaved Africans and indentured Europeans could provide it. Given their economic and social situation, indentured Europeans found that they had more in common with African slaves than they did with landowning elites that shared their European ancestry. In 1676, Virginia colonist Nathaniel Bacon harnessed the anger felt at widespread inequality between the elites and the landless to lead the largest interracial insurrection of the century. When the rebellion ultimately failed upon Bacon’s death, the landowning elites — fearing for their wealth and their lives — decided to inhibit further class-consciousness among the landless in the colony and promoted racial separation by constructing racial distinctions into the legal codes of the colony of Virginia. Europeans — regardless of wealth or landowning status — were established as “racially superior” under the law, and Africans were excluded from the ranks of colonial citizenship. Understanding that they could distract landless Europeans from directing their frustration at its root cause, the landowning elite crafted slave codes of colonial Virginia which would allow landless Europeans to project their economic, political and social anxieties onto the African population.

This scapegoating narrative has carried through the subsequent centuries of American history. In the aftermath of the Civil War, southern whites used the Freedmen’s Bureau to attack newly freed slaves for “keeping idle at the expense of the white man.” Similarly, whites in the late nineteenth century decried that “the Chinese must go” in response to rising numbers of Chinese immigrants replacing laborers on the railroads of the American West. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whites often reminded Irish immigrants (who had yet to be assumed into the evolving definiton of whiteness) that “No Irish Need Apply” for certain job listings. Countless other examples of the projection of the economic anxieties of whites onto non-white populations in the United States could be provided. Today, Trump’s narrative of Mexican immigrants crossing the border to steal American jobs and abuse the welfare system resonates much deeper with his white working class supporters than the rather more complex reality of free trade, globalization, corporate unaccountability and rising income inequality that is truly at fault for the decline of the twentieth century economic prosperity.

In the wake of Ronald Reagan’s 1984 landslide presidential victory, the Democratic Party commissioned pollster Stan Greenberg to conduct focus groups to study the many working class Democrats who defected from the party to support Reagan in the election. In his study, Greenberg found that these Reagan Democrats were mostly white low-to-moderate income voters from union households, who believed that their economic hardships stemmed from “reverse discrimination” against white Americans rather than the reality of rising corporate outsourcing. Greenberg writes that the “special status of blacks is perceived by almost all these [Reagan Democrats] as a serious obstacle to their personal advancement. Indeed, discrimination against whites has become a well-assimilated and ready explanation for their status, vulnerability and failures.” Greenberg’s observations of Reagan’s support from the white working class in the 1980s are nearly parallel to observations that could be made of Trump’s support today.

It is clear that many of Trump’s white working class supporters view racial competition, as Greenberg noted in 1985, as a “serious obstacle to their personal advancement” and that there is much historical precedent for this idea. Why, though, is this narrative of scapegoating people of color more prevalent than that of class antagonisms? Why do Trump’s supporters blame “welfare queens,” “inner city crime,” and “the browning of America” for the decline of social mobility and economic prosperity in the United States? Why do they not point, instead, to corporate greed, the outsourcing of labor, free trade agreements and rising income inequality as “serious obstacle[s] to their personal advancement”? The answer may lie in a simple comparison of the choices these voters face on election day.

For decades, the Republican Party has championed deregulated markets, tax breaks for the wealthy, free trade, privatization and cuts to the welfare state. The Democrats, on the other hand, have in recent history almost always provided some form of moderately progressive opposition. Yet in recent elections — and most notably this election cycle — Democrats have seen potential to expand their party’s base in the wealthy, college-educated suburbs of America. Numerous studies have shown that support for the Democrats’ social agenda — that of protecting reproductive rights, expanding protections for the LGBT community, prioritizing the fight against climate change — is highly correlated with college education and white collar employment. In this year’s election in particular, the Democrats seem to have doubled down on their solicitation of this wealthy, college educated, white collar vote. At a recent charity dinner attended by much of New York City’s elite, Hillary Clinton even joked “Every year, this dinner brings together a collection of sensible, committed mainstream Republicans. Or, as we now like to call them, Hillary supporters.” Is it such a surprise, then, that white working class voters aren’t flocking towards the Democratic candidate? Clinton’s remarks at the Alfred E. Smith Memorial dinner may have been in jest, but they do not misrepresent serious political shifts in this year’s election. The Democratic party has — whether intentionally or not — made great advancements in its support from wealthy, college educated, white collar voters. At the same time working class whites have, in equal measure, abandoned the Democrats. This realignment in the American electorate should come as no surprise if one understands that a political party cannot expect to expand its voting base with one group without concessions from another. But are ideological and cultural differences so strong between the college educated elite and the white working class that such a realignment should be expected?

Take a look at the 2016 Democratic party primaries and caucuses and the answer becomes abundantly clear. In 2016, Hillary Clinton was pitted against self-described Democratic Socialist Bernie Sanders in a bitter primary battle that revealed the growing fissures in the Democratic party. During the primaries, Clinton’s campaign focused on her more than thirty years of political experience and her effectiveness as a politician, while Sanders ran on a platform of national single-payer healthcare, tuition-free college education, opposition to “the billionaire class,” addressing income inequality and igniting a nationwide “political revolution.” Perhaps the most revealing statistic of white voters in the Democratic primary was the correlation between income and candidate preference. According to CNN’s exit polls, in New Hampshire (with a Democratic primary electorate that was 93% white), Sanders won voters with an income of less than $50,000 by a margin of two to one. In states with similar demography Sanders also proved popular among working class voters winning 55% of their votes in Connecticut, 56% in Massachusetts, 58% in Wisconsin and 60% in West Virginia. Not only did the primary reveal that Clinton repeatedly lost the votes of the white working class to her more economically populist opponent, but she was the clear favorite of the liberal elite. In Weston, Massachusetts (median household income of $192,563) Clinton won 68% of the vote, in Darien, Connecticut (median household income of $175,766) Clinton won 70% of the vote, and on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, New York (median household income of $117,903) Clinton pulled roughly 80% of the vote. In the end, Clinton’s 55% of the national popular vote earned her the necessary delegates to clinch the Democratic nomination, but many of Sanders’ supporters — economically populist and less wealthy than Clinton’s supporters — staged demonstrations at the party convention in Philadelphia in protest of Clinton’s nomination. If anything, the Democratic primaries revealed that the white working class rejects the political establishment that they believe has done little to address rising income inequality, corporate unaccountability, Wall Street greed, the outsourcing of labor, and the decline of economic opportunity in the United States. Why, then, have so many of these voters turned to billionaire Donald Trump?

In January 2015, Democracy Corps, a leading political consulting firm for Democratic candidates headed by Stan Greenberg and James Carville, published public opinion research on the political psyche of white working class voters in the United States. In the study, Greenberg and Carville found that, contrary to popular belief, white working class voters support a myriad of progressive proposals by wide margins on the condition they are accompanied by governmental reform. The study found that white working class voters support making higher education and childcare more affordable, raising the minimum wage, raising taxes on the wealthy and tougher regulation of Wall Street when these proposals are prefaced with a narrative that acknowledges the influence of big money in elections, of corporate lobbying on the legislative process and of out-of-touch politicians protecting special interests. Specifically, the study found, among white working class voters, a 13 point increase in support for the Democrats’ economic agenda when prefaced by an agenda for governmental reform. This is the key to understanding why both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump share such wide and enthusiastic support from the white working class. The campaigns of both Trump and Sanders were anti-establishment, called attention to the influence of big money in politics, criticized the liberal elite and its support for Hillary Clinton, opposed NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, openly discussed income inequality and presented proposals to restore economic opportunity in the United States. Obviously, the solutions that each candidate proposed were vastly different, but both shared a populist flavor that prioritized the financial struggles of the white working class and took on the ruling establishment. The problem with Hillary Clinton is that, to many of these voters, she is the epitome of the ruling establishment.

Hillary Clinton served as First Lady of Arkansas, as First Lady of the United States, as U.S. Senator from New York and as Secretary of State. From 1986 to 1992, Clinton served on the Board of Directors for Walmart, Inc. The recent leak of her speeches to Goldman Sachs revealed that she told her audience of Wall Street financiers that she believes politicians must have “both a public and private position” on policy issues especially when the public is “watching, you know, all the back room discussions, and the deals.” From the perspective of many white working class voters, regardless of Clinton’s own economic proposals, she too closely embodies the liberal elite and the ruling establishment to be considered as their candidate. In Hillary Clinton, these voters are reminded of the hardened ideological and class differences that have developed between the white working class and the upper class, college educated constituencies that the Democratic party has gradually drifted towards over the past few decades.

The Democratic party’s shift away from the white working class has created a void which Donald Trump fills. Ask Trump supporters why they like him and you’ll likely get some form of response that praises his ability to “tell it like it is” and “say what’s on his mind.” To the white working class, Trump’s frankness comes from his status as an outsider to the political system; a refreshing break from the “politically correct” rhetoric of the Bushes, the Clintons and other political elites. Why though, has the white working class turned to a billionaire real estate mogul to restore their faith in the American Dream? Although it may seem ironic, to these working class voters, Trump’s perceived financial success represents a personification of the achievement of the American Dream. When you hear Trump supporters say that they believe that he will “run the country like a business,” they are not speaking of fiscal responsibility, but rather of Trump restoring economic opportunity to the United States. Are some of Trump’s supporters active racists? Of course, but many more are disaffected blue collar Americans that feel betrayed by the Democratic party’s abandonment of their political and economic interests. Most of Trump’s supporters didn’t wake up one morning and suddenly realize that their economic situation could be improved if a wall were built between the U.S. and Mexico. Rather, in the absence of attempts from elsewhere in politics to prioritize their economic interests, these voters turned to the leading anti-establishment voice calling to restore economic opportunity and to ‘Make America Great Again.’ It is painfully ironic, though, that this message is broadcast by a man who spent his whole life outsourcing the jobs that he pledges to bring back, scamming the “poorly educated” whom he claims he loves and failing to acknowledge his own culpability for the political and economic system that has impeded America’s “greatness.” •

[…] View Original: Contextualizing the Rise of Donald Trump […]