Our Crozier-Williams Student Center (Cro) produces 593 tons of carbon dioxide a year. A 37 acre forest on the Las Delicias Farm in Costa Rica absorbs 320 tons of carbon dioxide annually. But what do these two seemingly juxtaposed locations have in common?In 1999, Conn became the first college in the US to sponsor a forest through an organization based in Mystic, CT called Reforest the Tropics (RTT). For a $30,000 price-tag came 25 years of sequestration, a sigh of relief that we had compensated—at least partially— for our Cro emissions, and the promise that we had invested in “the most transparent carbon offsets possible.”

RTT works with both businesses and educational institutions to offset carbon emissions by planting forests throughout Costa Rica. Their model emphasizes the role of local farmers, who are paid to maintain the forests and in return sell a percentage of the trees grown for profit. The sponsors of the forests do not have a direct role in their preservation.

Though I was initially wary of a profit-driven forest model, RTT does have clear boundaries in place. The thinning does not start until a forest is five to six years old. From here, 20% of trees are cut down for lumber every four years. RTT argues that this thinning is both necessary for the health of the forest —- intermediate disturbance, disturbance that is neither frequent nor rare, allows strong plant life to survive while eliminating weak plant life— and for incentivizing landowners. The RTT website explains, “The RTT model strives for permanent carbon storage by creating a financial incentive for farmers to maintain and profit from their sustainable forests.” Essentially, the lumber production model ensures that farmers will not sell their land or use their land for an alternate activity.

Though my concerns about thinning forests for profit were mainly mitigated with an exploration of the RTT website and a conversation with Executive Director of RTT, Greg Powell, I stumbled upon another bit of information that stood out to me— a list of the businesses that sponsored forests through RTT. The list includes: Torcon Inc, Superior Nut Company of Cambridge, Loud Fuel Company, New London Public Schools, and the Connecticut Municipal Electric Energy Cooperative (CMEEC). From my research, the CMEEC seems to be the only business that highly prioritizes a sustainable model as one of its major goals. This made me question whether these companies were sponsoring forests because they believed in protecting the planet or rather because they wanted to portray a positive public environmental image.

Loud Fuel Co. was in my opinion the most problematic sponsor. According to the Loud Fuel Co. website, “We are a family owned business and have served customers on Cape Cod, with delivery of home heating oil for over 35 years.” As the daughter of a small-business-owner, I have no interest in undermining small businesses. As an environmentalist, however, I do have to recognize the negative impacts of the oil industry on global temperatures, rising sea levels, habitat depletion, deforestation, and more. It seems wrong that an oil company is sponsoring a forest in far-away Costa Rica as a way of mitigating the large-scale environmental damage perpetrated by oil giants.

Powell had a different take. “Fossil fuel use is part of our immediate future. Hopefully, 20 years down the road it will be different,” he commented. “My philosophy is we need to get roots in the ground. I’ve never come across an organization I wouldn’t consider planting for. If Exxonmobil came to us, yes of course we’d plant.” Director of the Arboretum, Glenn Dryer, had a similar opinion in terms of Conn’s involvement with RTT. “Outright reduction of carbon emissions is obviously a more direct way, but in the meantime, absorbing the emissions is very appropriate,” he argued. Both Powell and Dryer acknowledged that businesses should ideally be cutting down on emissions as well as offsetting them, but as Powell put it, “We need every tree. We need them all.”

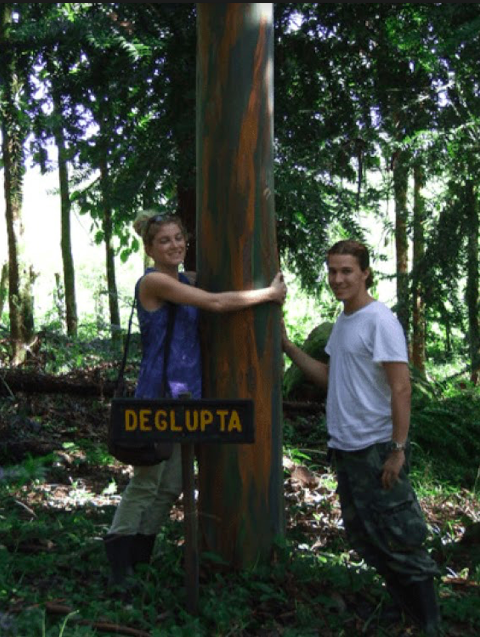

Photo courtesy of Reforest the Tropics.

Overall, I am torn in my assessment of our RTT partnership. On the one hand, I want our earth to be blanketed with as much forest as possible. Forests act as natural carbon sinks, meaning they sequester the excess carbon dioxide we produce without chemicals or human interference. Other carbon sequestration techniques, as detailed by the RTT website, include “fertilizing the oceans, a risky method that will exacerbate the problem of an already too acidic ocean [and] smokestack scrubbers, which are estimated to remove and store CO2 for a price of approximately $200 per metric ton.” Forests are clearly the most environmentally friendly and cost effective model of carbon sequestration, so should the companies behind their sponsorship really matter? If the outcome is a forest, is it important that the corporate intention is advertising, saving face, or greenwashing?

As the idealist I am, I have to argue that it does matter—that RTT’s relationship with Loud Fuel Co. does not sit right with me. Although I want to support the preservation of forests as much as possible, I think a larger emphasis should be placed on whether the companies that are sponsoring forests are actively trying to reduce their emissions—perhaps this should be a requirement for participation in the program. Office of Sustainability Fellow, Grace Berman ’18, commented on Conn’s relationship with RTT. “I think what we should really be doing is investing in renewable energy on our campus so we’re producing less carbon ourselves.” She continued, “I don’t think our environmental sustainability can be dependent on us preserving a forest that we have no connection to.”

Though I have offered some critiques throughout this article, I do not aim to dissuade Conn from partnering with RTT. I think that this organization loves trees as much as I do, if not more. I believe it is an organization that takes into account local communities and farmers living in Costa Rica. Without RTT, 138 hectares of applied research forest would not have been planted. I simply encourage all of us to recognize our role and our privilege. Our college was able to sponsor a forest for $30,000 in order to make our Cro emissions disappear without so much as looking at our campus and the changes we could make here. I heed Berman’s warning on this one: “It’s kind of a cop out.”