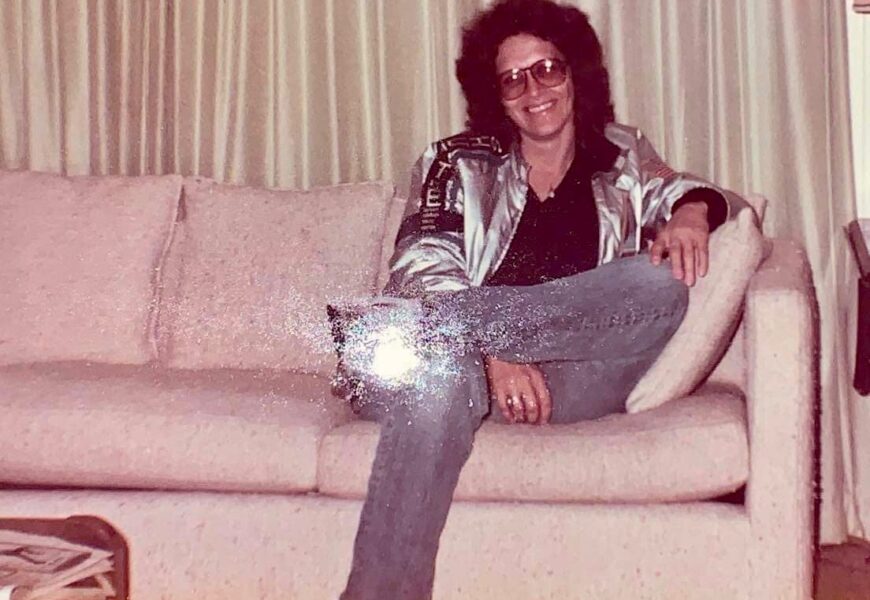

Image courtesy of Blanche Boyd.

Blanche McCrary Boyd brings a butane lighter and metal trash bin to the first day of all her writing classes. She tells students to write on a piece of paper something they would never want anyone else to see. After a few meditative minutes, she leads the class outside, places the bin at the top of Tempel Green, tells students to toss in their writing, and lights a flame. The writing students had been most afraid to set down turns to ash. “I want students to know their writing belongs to them.”

She arrived to her first day of teaching at Connecticut College in 1982, newly sober, with wild, wind-strewn hair, blue jeans with the knees torn out, smoked glasses, and what the then-head of the English department called “the dirtiest shoes he had ever seen.” By then, at thirty-five, she had already published two novels: Nerves in 1973, and Mourning the Death of Magic in 1977, which she has since disowned. Boyd went on to publish three more novels and a collection of autobiographical journalism during the span of her forty year career as a professor and writer in residence at Conn.

Despite her history as an accomplished writer, Boyd does not gloss over the hard work involved in success. Her advice to aspiring writers is “Stop if you can.”

Many of her students choose not to stop. Boyd feels as though she has had “more impact as a teacher than a writer.” In her office, there is a shelf comprised entirely of published work by her former students. That list includes David Grann, Sloane Crosley, and Jazmine Hughes.

Boyd often tells her students there are two ways a writer must read: as a reader, and as a writer. A reader allows themselves to experience the story, and a writer returns afterward to examine how the author achieved their intended effect.

One of Boyd’s teaching methods is to read literature aloud in class, and encourages students to do so in their own time. She often teaches from the works of Tobias Wolff, Lorrie Moore, and Raymond Carver. She mimics the ways in which she wants students to read, first reading stories from start to finish so that they wash over students; then, she returns to the text and illuminates techniques.

Another common assignment is to submit a page of anonymous work, which Boyd then shuffles through and reads throughout class. Hearing work aloud, esteemed literary work in junction with student classwork, attunes the ear to details and clarifies the quality of the work. In rare, formative moments, students have the opportunity to see how their work moves others.

“When I was young, I heard Riders to the Sea by John Millington Synge read out loud. I felt something at the back of my spine, like I had no idea anybody could make me feel like this by writing. And I wanted to do it.”

It was after she heard Riders to the Sea that she began devoting time to reading and engaging with literature, and cites Pale Horse, Pale Rider and The Jilting of Granny Weatherall, by Katherine Anne Porter, and Tell Me a Riddle by Tillie Olsen as lifelong favorites, some of which she still assigns for students to read to this day.

Beyond her career as an author, Boyd has had a life full of twists and turns. She attended Pomona College for her bachelors degree and received her masters by way of the Stanford Stegner Fellowship in 1971. During this time she relapsed into alcohol and drug addiction. She divorced her husband, moved to Vermont to join a commune, and then moved to New York to become a writer for The Village Voice. She lives and writes through the lens of a “lesbian alcoholic,” and has been told by Rita Mae Brown, “You hit rock bottom and came up laughing.”

“Life is hard,” said Boyd seriously. “I hope my children never find out.”

Boyd has two children with her wife Leslie, twins who are both scheduled to graduate from college the same week she plans to retire, setting her up for three total graduation ceremonies in a seven day period.

“What’s killing me is I’m going to miss the opening game of the Connecticut Suns,” Boyd said, a comment characteristic of her wry humor.

The prospect of retirement itself doesn’t faze Blanche in the slightest, who, when asked how she feels about leaving her teaching days behind, simply said, “I’m ready.”

“I have no idea what I’m going to do,” she admitted. “I wouldn’t mind writing something that’s happy.”

One thing Boyd will miss beyond any doubt, however, is the connections she’s been able to make with her students, not just as writers, but as people.

“I love teaching. I feel like I’m able to give what I wish I had gotten. The kind of belief in literature and that I care about my students as individuals. I think, or at least hope, that most of my students feel seen. For some people that’s uncomfortable, and for some it’s like okay, she’s listening to me. And I am. I’m really listening.”

Do a Master Class on writing your way.

Dear Blanche,

Loved this article and can imagine you are a remarkable force in the classroom with eyes and heart wide open – pen at the ready. My mom so enjoyed overlapping with you at Conn College – no doubt that campus will miss you sorely. Best of muses in your next chapter – we’ll be seeing you – and congrats to your family on the upcoming graduations!

Beautiful profile. It brought back memories. So many former students, when they sit down to write now, have Blanche’s voice in their head. And what a voice!! We’re lucky to have passed through her classroom.