Hendrik Andersen and John Briggs Potter in Florence, Andreas Andersen. Possibly the first publicly displayed painting clearly of a homosexual couple.

At a grand display of nearly three hundred pieces, spilling down staircases and halls for a staggering three-story expanse, the new exhibition from acclaimed queer art historian Jonathan D. Katz and co-curator Johnny Willis, “The First Homosexuals: The Birth of a New Identity, 1869-1939,” is truly a sight to behold. The title alone is enough to have sparked petty controversies online, but it holds a simple truth: prior to 1869, the word, and therefore the identity, homosexual did not exist. The exhibition, an extensive survey of art history as a location of queer history, takes the viewer through this development in a visual shift: queerness was no longer something you did, but something you were.

At the very top of Wrightwood 659 (a beautiful and architecturally phenomenal new exhibition space in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood), many others and I, of all ages and faces, clustered together, having the great honor of being able to attend one of the curator’s tours, led by Katz and Willis.

Though I probably could have gone back every other day of the summer and never have grown bored with it, my favorite section of the exhibit, if I had to choose, is the one we started labeled “Before the Binary,” the single room spanned societies from the neo-classicism of Europe to Edo-period Japan, to the indigenous societies of South America, even post-colonization Lima, the Ottoman Empire, and more.

Many societies, prior to European colonization and the forcible dissemination of European cultural ideas, did not differentiate between same-sex and opposite-sex relationships as Europeans did, and even then, some did not have distinct enough senses of sex and gender to begin to differentiate said relationships.

An artist that’s always interested me, Simeon Solomon, had two works exhibited: one in particular, called “‘Bride, Bridegroom, and Sad Love,” was meant to point out, as the exhibition’s program reads, that “people often engaged in both same-sex and opposite-sex encounters at different stages of life.”

Bride, Bridegroom, and Sad Love, Simeon Solomon

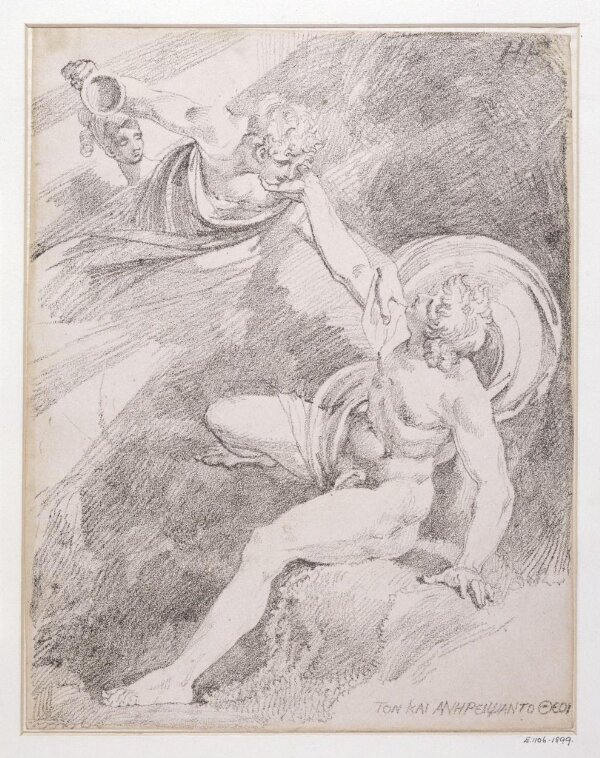

Heavenly Ganymede, Henry Fusili

These other understandings of sexuality and gender, however, are halted by portraits of Karl Maria Kertbeny and Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, the two German men responsible for the coining of the term and the concept of homosexuals. This also had to do with the introduction of the idea of the ‘third sex,’ or ‘sexual inverts,’ which described the initial belief that, for example, homosexual men simply were female souls inside of a male body, an idea that eventually went out of fashion. On this sexology and creation of identities, Dr. Katz said: “The chasm they created between homo and hetero sexuality produced the very culture that we live in now.”

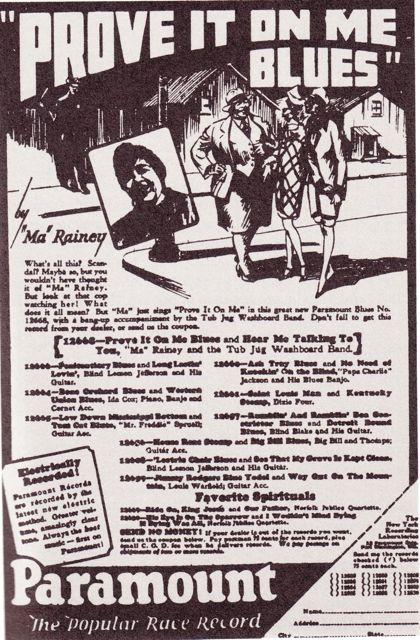

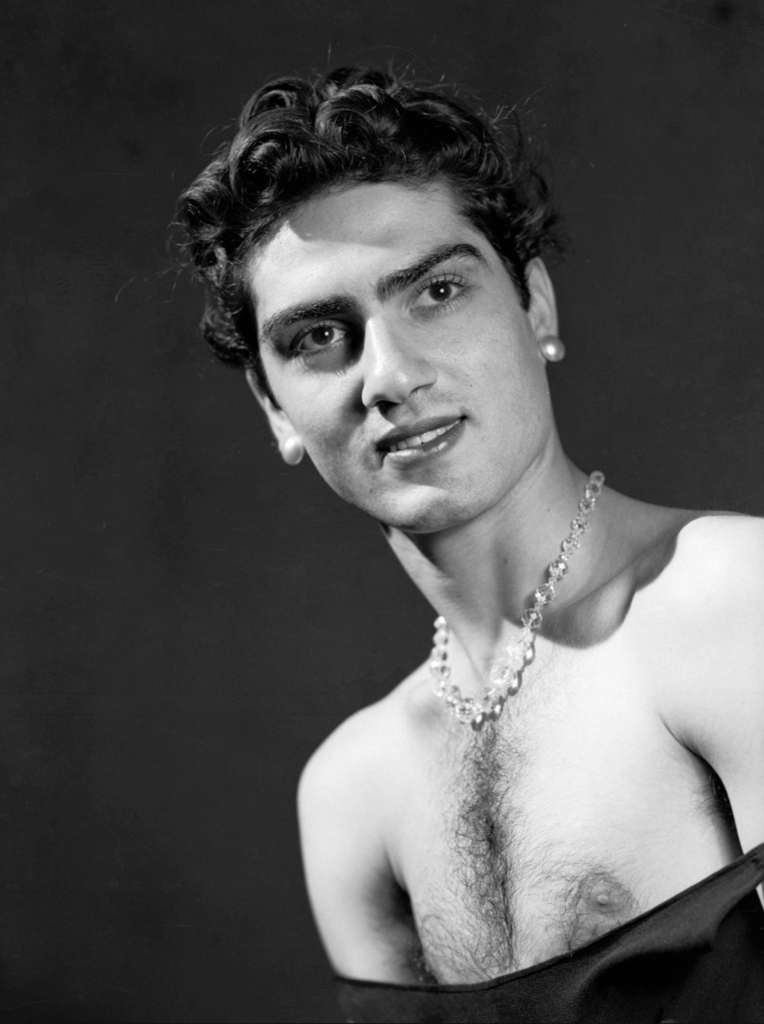

From there, the exhibition swerves between time periods, between identities, and across the gradual shifts of how we understand ourselves and our identities: from the artists and writers who helped define what homosexuality looked like, such as Oscar Wilde or Gertrude Stein, to later queer performers like Josephine Baker and Ma Rainey. Featured artists included some of my favorites, such as John Singer Sargent, and other highlights such as Van Leo, Florence Carlyle, Thomas Eakins, Andreas Andersen, Florine Stettheimer, and dozens more.

Prove it on me blues, Ma Rainey

1942 self portrait, Van Leo

The Guest, Venice, Florence Carlyle

The Wrestlers (unfinished), Thomas Eakins

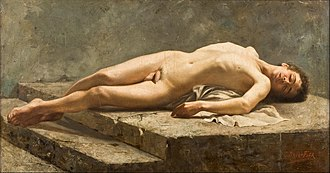

One visual shift of note that the exhibition stops to portray is that of the shift from queer art, or more accurately, gay art, primarily portraying adolescents and youths into portraying a more muscular, explicitly adult understanding of masculinity. Dr. Katz posited that the portrayal of nude adolescents, prevalent especially in neo-classicist paintings, was part of the reason that The First Homosexuals was denied by some of the most prominent spaces in the country and internationally–in my opinion, likely simultaneously with a present rise of conservatism and fear of backlash against queer subjects. However, Katz and Willis propose a different understanding of the presence of youth and adolescence in early queer art: rather than entirely the obvious and unsavory interpretation, it’s more accurately understood as a way of trying to visually represent the androgyny of the ‘third sex,’ and therefore attempting to create representations of homosexuality without explicity showing homosexual acts, as was the intention of much of neo-classicist art.

Reclining nude (Abel muerto), Carlos Baca-Flor

Of course, as the ideas of the ‘third sex’ and sexual inversion were left behind, there were still lengths to go before we happened upon our contemporary understandings of queerness, where gender presentation is only a part of a larger, complex identity. For a time, queerness was still only assigned to the effeminate, ‘receiving’ figure in a relationship (Katz shares a story about an early 20th century sailor “offering” himself up to his roommates– of course, there was nothing at all queer about the other men taking him up on the offer).

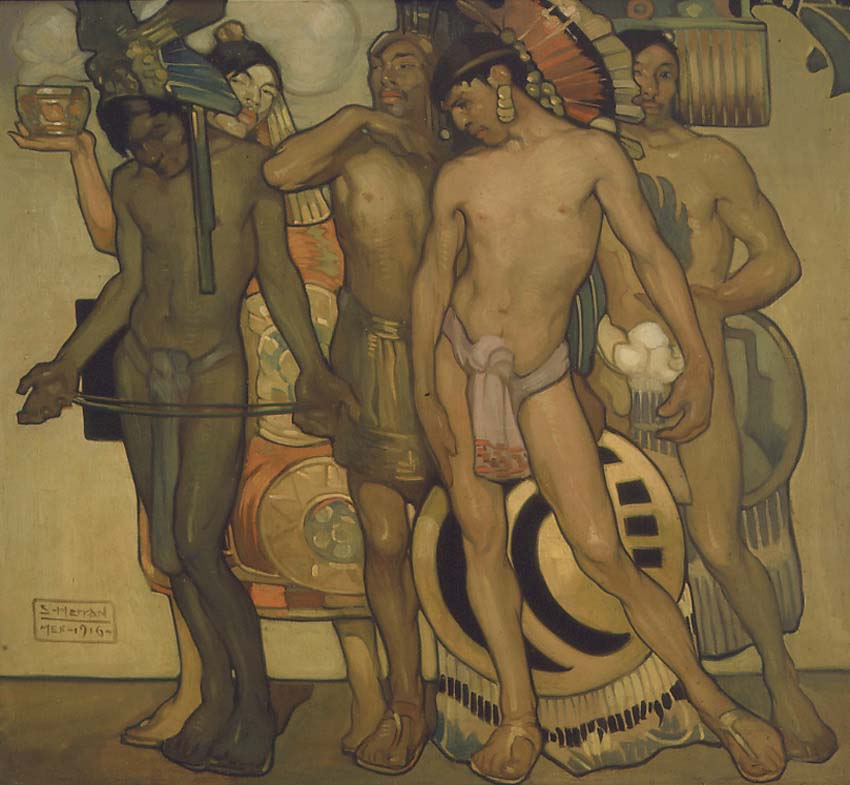

Underlying much of the exhibit, though, was the complex relationship between gender, sexuality, and fascism– or, more generally, how gender and sexuality have been perceived by and have interacted with different ideologies. Most otably, of course, this manifests in the way that indigenous queerness has always acted as a form of resistance to colonialism– Saturnino Herran’s Nuestros dioses antiguos is a stunning highlight of the exhibition, and accompanies many other paintings and photographs highlighting indigenous North and South American gender non-conformity.

Nuestros dioses antiguos, Saturnino Herran

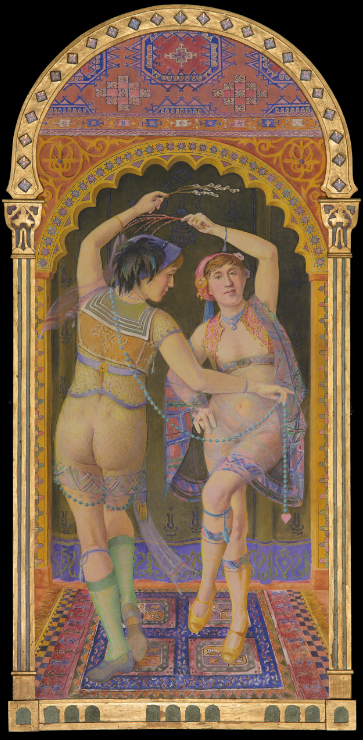

Additionally, though, the exhibition explores the ways in which these distinctions were not clear-cut. Class differences define the early rooms of the exhibition, where some could afford licenses from the French police to crossdress, the wealthiest pay their way out of jail time, and empires use both homosexuality and homophobia as tools of propaganda and insult. Other queer artists, such as Romaine Brooks and Elisar von Kupffer, directly associated with fascists or Nazis, a fact that is especially visually present in those of von Kupffer’s works on display. These works were only uncovered by Katz and Willis a few years ago in Switzerland, where they had not been displayed in many decades.

La danza, Elisar von Kuppfer

At the very end, the exhibition leaves its viewers with a particularly shocking image: the Nazi’s burning of Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science. The exhibition provokes us to think of our identities as contextual, shifting, and deeply political things, and to understand ourselves and our sexualities as part of a larger history of resistance, invisibility, visibility, and change. It warns us of the dangers that we as humans and we as queer humans meet in the face of governments that work for our silence, complicity, and eradication.

Lili with a feather fan, Gerda Wegener

Untitled [Two Black actors (Charles Gregory and Jack Brown), one in drag, dance together on stage], Unknown Photographer