Courtesy of Lexie Dixon ’27

On a quiet summer afternoon, I took my first-ever visit to the Lyman Allyn Museum. I brought my mom, a high school English teacher who often spends the precious hours of her weekend creating ceramics in the basement of my family’s home. While we explored each section and level of the museum, one exhibit caught her ceramicist’s eye.

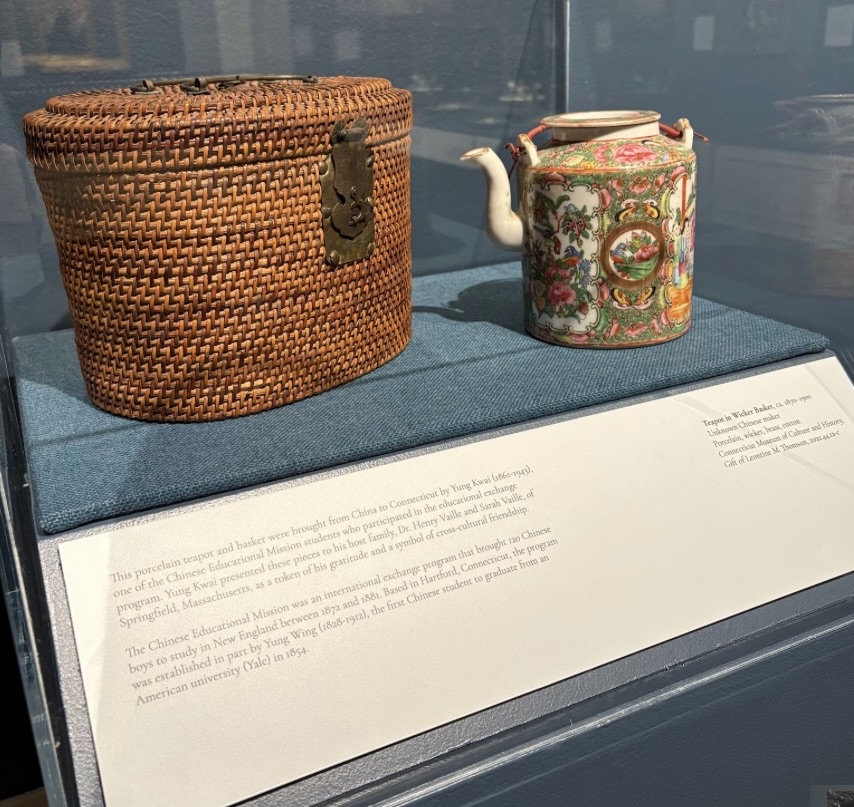

This summer, the Lyman Allyn Art Museum held an exhibit from June to September 14th, titled “China from China: Porcelain and Stories of Early American Trade.” Its collection was expansive. In addition to showcasing highly decorated porcelain vessels acquired through 18th and 19th-century trade between America and China, the exhibition also displayed embroidered silk textiles, botanical samples, historical documents, portraits, and landscape paintings.

In a written introduction to the collection, the museum’s director, Sam Quigley, highlighted the exhibition’s significance in revealing “how global trade shaped local lives.” Merchants and sailors with the means to embark on transpacific travel brought home goods that became a lasting part of the material makeup of their homes. Walking through the collection, one’s eyes are drawn to the delicate dinnerware decorated with iridescent glaze and painted details.

In addition to the beauty and intricacy that this exhibit presents, informational plaques beside each display provide additional economic, political, and cultural dimensions to the artwork, sure to delight tea fanatics and history lovers alike.

One display case held a colorful teapot and its wicker basket container. These items, created by an “unknown Chinese maker,” were brought to Connecticut at the end of the 19th century by Chinese Educational Mission student, Yung Kwai.

Courtesy of Lexie Dixon ’27

Another area showcased a portrait of the powerful and influential Chinese merchant, Howqua. The painting is oil on canvas by the artist Lam Qua, from the mid-17th century.

To briefly summarize, the artifacts on display arrived here from China just a few centuries ago, as early as 1784. According to a curatorial guide for the exhibit, “Connecticut was a significant player in the China trade,” as merchants traveled on ships such as the Empress of China to conduct direct trade with China (Eric Jay Dolin). Such ships left from well-known Connecticut ports, including New London.

Following the Revolutionary War, Americans sought economic stability and independence untethered from the British. Traders imported porcelain, a variety of teas, silk, and furniture from China in exchange for quantities of seal skins, otter pelts, and sandalwood. Drawing extensively from these resources resulted in their decimation within the local area, and harmful environmental imbalances ensued. Another negative implication of this trade was that it facilitated increased transportation and sale of opium, which initiated not one, but two wars spanning the mid-19th century, known as the Opium Wars. These instances exemplify some of the broader impacts of early Chinese-American trade.

The museum’s director, Sam Quigley, wrote: “…our inherited material culture reflects the complexities of our interconnected world.” Not only do the artifacts of the exhibit convey an exchange of goods, but they also make evident a connection between the craft practices of early colonial America and those of China. While porcelain was extremely desirable, it was by no means affordable. The introduction of these high-quality Chinese ceramic goods inspired American craftspeople to replicate the aesthetic of porcelain with the earthenware clay available to them. Ceramic styles such as pearlware, creamware, and whiteware emerged over time as attempts to mimic the iridescence of porcelain clay (Deetz 1996, 68-88).

The aspiring archaeologist in me was amazed to see fully intact porcelain bowls, teapots, and platters, as opposed to weathered sherds of pottery found in the soil at a dig site. Whole artifacts, like those exhibited, are treasured, kept as family heirlooms, preserved for decades, and eventually acquired by museums.

I spoke with the curator of “China from China,” Tanya Pohrt, about how the exhibit came to be and why the Museum chose to highlight so much history throughout. A collaboration between the Lyman Allyn and the Dietrich American Foundation initiated the exhibition, but Pohrt was determined to centralize the significance of Connecticut history with locally significant pieces. This led to further outreach to and connections with nearby museums. The work of the Lyman Allyn Museum provides essential context to the current reality of international trade that might have otherwise been left in the past. The story, instead, has been expanded in a meaningful and visible way.

Viewing this exhibit left me with a renewed understanding of the history and politics of early trade in America. I wondered, though, if the incredible ceramic pieces were ever intended for daily use by the people who previously owned them. Have they always been stored on the top shelf with the utmost care? Many appeared in pristine condition, possibly indicating safekeeping from the wear of food, drink, or damaging utensils for much of their existence.

Presently, the porcelain pieces are designated only to be looked at; they have relinquished any utilitarian function once entering museum possession. They are kept behind protective glass and not exposed to harsher environments like the College’s dining hall. Something more rugged and practical is needed to withstand the daily life of a college student.

I use a sturdy ceramic mug crafted by my mom nearly every morning for my tea. For the first time, I’m beginning to consider how my life has been impacted by the distant history of trade between America and China.

Although the “China from China” exhibit is now closed, the Lyman Allyn Museum is an excellent place for those interested in examining how art and Connecticut history collide.