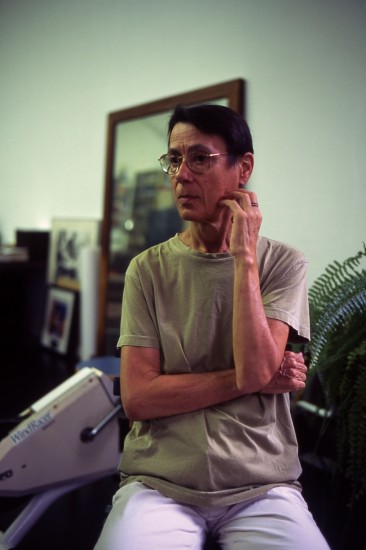

Yvonne Rainer

Last Tuesday, a pioneer of postmodern dance and avant-garde filmmaking, Yvonne Rainer, visited Connecticut College. She came to speak with several classes and to screen one of her films. When I heard that she was going to visit my freshman seminar I expected someone eccentric and self-serious. But Yvonne Rainer turned out to be a relatively down-to-earth person with a pleasant sense of humor about her work and a surprising amount of modesty, considering her impressive background. She told our class, frankly, “I was never encouraged by my parents to be anything but a housewife.”

Since her birth in 1934 she has been an actor, dancer, poet, choreographer and filmmaker. Her seven films have received awards from the Sundance Film Festival, the American Film Institute and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Her choreography has been commissioned by some of the biggest names in the dance world, including Mikhail Baryshnikov, which has earned her numerous fellowships.

It’s surprising how far she has come considering where her career in dance began. She began dancing on a whim when she tagged along with a friend to a dance class. “I was never very gifted,” she said. “In class I always had to follow the person in front of me.” But Rainer had no question about how she got to where she is today. “I was strong and loved to dance, and most importantly had no idea of my limitations.”

Rainer, early in our class interview, stood up and gave a demonstration of the minimalist choreography that has made her so famous. She raised her index fingers to her face and pointed at her cheeks. She then hooked her fingers into the sides of her mouth and pulled horizontally. The index fingers, still extended, then left her mouth and followed her body downward until they reached her ankles, at which point she momentarily slumped over before pulling herself back up to a standing position.

Her style is strange and abstract, but it’s a deliberate weirdness that makes a definite point. I was fascinated by Rainer’s explanations of her dances during the interview. Her pieces have a certain silliness that is often juxtaposed with serious political and social issues. They’re spontaneous, unpredictable and challenge the conventions of dance. She described her work as “an argument with what has come before,” and demonstrated the subtleties in some of her pieces that veer in distinct ways from the norms of classical styles.

Later that night I got a taste of her avant-garde filmmaking style when Lives of Performers was screened in Olin Auditorium. Made in 1972, it was her first film and remains one of her most influential. The movie began with a definition of the word “cliché”. It’s fitting, for the story itself is rather trite and the characters seem to represent common movie stereotypes. It revolves around a man who can’t decide between his plain housewife and his glamorous “other woman,” both of whom he loves. What’s stunningly creative about the story is how it’s told. It starts as a documentary of a rehearsal for one of Rainer’s dances, but then subtly melds into what seemed like a fictional melodrama, blurring the line between what’s real and what’s not.

There were many sharp breaks from cinema conventions that stood out. None of the dialogue in the film could be heard. Instead the actors explained what their characters’ were saying and doing through voiceover. Occasionally lines of dialogue would appear on screen as text. The movie was also completely devoid of music, and there were whole scenes that went on in silence. The camera seemed to be completely uncompromising, as it rarely followed the actors and often strayed from their faces to awkwardly focus on their feet or torsos. As a result, a brief scene during which the Rolling Stones’ “No Expectations” played, or the very few moments where dialogue came directly from the actors mouths were jarring and served to juxtapose accepted methods of storytelling in film with Rainer’s unique style.

After the movie was over, Rainer stood in front of the audience and said “I forgot to warn you that parts of this film are like watching paint dry.” The audience laughed in partial agreement, but I think many of us were able to see why the film was important. It toyed with ideas that no filmmaker had ever thought of and used innovative methods to convey an impactful story. The avant-garde can be hard for some people to swallow, but Rainer seems to focus more on her art than what people may think of it. About her own work Rainer said, “Call it art, call it creative, call it whatever you want, I don’t care.”