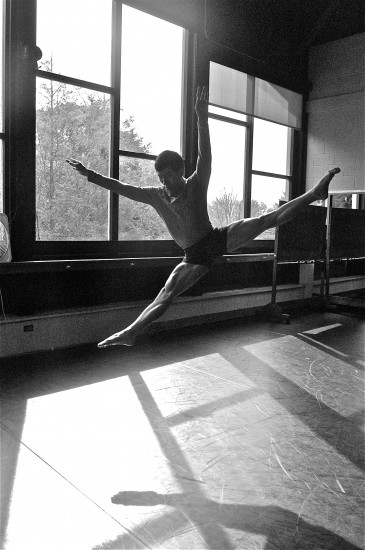

Photo by Kira Turnbull

I was out of breath by the time I arrived at the Myers Dance Studio, ten minutes late. A woman tapped on my arm. She was carrying a baby. “No shoes,” she said, glaring at my shoed feet.

I held my sneakers loosely in one hand as I slid in my socks across the floor towards my writing professor. She had her hand on an Asian guy’s shoulder. “This is Wayne,” she said. “He’s a good one. I’m sorry to give him up.” Wayne smiled pleasantly at me. Then he fell backwards and became an arch, his hands and bare feet all flat on the floor.

“Uh, hi,” I said. “We can go downstairs. But I’ll wait until you’re done stretching.”

“I’m just waiting,” he said calmly.

It was at this point that I realized I had no idea where I was or what the hell I was doing there. Interviewing is not an easy skill, especially when each of your subject’s motions makes you feel less and less at ease with your own physical ability. As Wayne lead me down a staircase into a familiar part of the student center, I ceased feeling stupid long enough to wonder: how do the professionals do this? Aren’t they nervous to interview George Clooney or Barack Obama? I’m intimidated enough as it is, and I’m interviewing some guy named Wayne.

As it happens, Wayne proved almost as soon as my flat, directionless interrogation began that he isn’t just “some guy.” The theme of the interview, as my professor so optimistically stated in the week before’s class, was “flying and falling.” I was falling all right. Wayne is one of the most fascinating people I’ve ever met and I had no idea how to handle him.

We sat at a table facing one another. Wayne was wearing a tight, gray shirt with rolled up sleeves. His arms were in his lap; I could not see his hands. I asked him about his origins, hoping for a metaphysical answer that would translate into a brilliant narrative.

He responded with something about basketball and Singapore and his brother. My hand wrote down everything that came out of his mouth without consulting my brain first, which is just as well because I wasn’t paying attention to a thing he was saying. Instead, I was trying to figure Wayne out. He’s a good-looking guy. He has a symmetrical face and clear skin. But his jaw was clenched in a way I’m not used to; the words and syllables were clear and controlled, rolling off of his tongue like beads of mercury. I found myself scared to make direct eye contact.

“That’s interesting,” I said to his answer. It probably was. “So what types — types? Styles? — of dance have you done?”

“In the army they taught us Jazz dance,” he said. “And we did some Chinese folk dances. Our company performed for other troops and for the community, acting out what we referred to as ‘national values.’”

The army! He was in the army back in Singapore. I suddenly understood the coolness. He told me about performing in front of an audience of thousands in a convention that showcased Asian aerospace technology. He told me about performing in the streets of Singapore in the International Basking Festival.

“In the U.S.,” he said, “you have street performers all over the place. But in most other countries you need a license. It’s called a basking license. And so they have an annual festival to promote basking. Hey!”

He was waving to someone. I didn’t turn around. “Well, in some American cities you probably aren’t allowed to just perform without permission,” I said, trying to appear wise. “Let’s get to a more difficult subject: what are times when you have felt like you are flying and felt like you are falling?”

Wayne immediately outdid me. “I believe in planning. I believe there is order in the universe and order in God. In the past I have had many dreams while training in which I can perform the move I am training for. Every time I have one of those dreams, I can feel myself performing the move. Then, when I finally achieve the performance in real life, like when I did a split-jump for the first time, it feels exactly how it did in the dream. The dreams are answering me when I ask to learn something new in dance. My body simply has to catch up to the dream.

“Dancing is flying,” he said. “You fly when you lose conscious control and your body takes over.”

“What about falling?” I asked. “When have you fallen?”

Wayne hesitated for a moment. He broke into a smile as he greeted another passerby, then his lips relaxed once again. “I’ve never really been afraid of falling,” he said. “I’ve stumbled in performances and dropped flags. One time…“ His arms shot up from below the table. He cascaded them over each other in a loop. I was astonished. “One time I was twirling a flag like this. And I dropped it. I kept going; that’s all you can do. But all I needed to do was wait another eight counts and I was back where I had dropped the flag.” He windmilled his arms rapidly. His hands were like a torrent of water. In a flash he had nabbed an invisible flag from somewhere next to the table and transitioned smoothly back into the dance. “I got it again and continued.”

“Wow.”

“It’s like my choreographer told me. ‘Once a performance is over, it’s over.’ There’s no reason to freeze or get scared.”

“Have you ever physically fallen?”

“Many times in rehearsal,” he said. He nodded to yet another person walking by then looked back at me. His eyes were caves that stretched back far beyond my vision. “I was riding my bicycle downtown this last summer and a car crashed into me. Before I knew it, I had leapt off of the bike and tumbled on the ground. And thank God.“ Wayne placed his palms together in prayer. “Thank God, because I would have been dead otherwise.”

“How do you think you were able to leap that quickly?”

“When you fall so many times during practice, your body remembers. Your body remembers how to fall. I black out between falling and landing. My body takes over. I am not afraid to lose control.”

I thought about Anne Rice’s book Interview with a Vampire. At the end of the two-hundred-year-old vampire’s story, the teenager who has been listening begs to become just like him. I thought about begging Wayne to teach me how to fall. I saw within him some earnestness, some faith that I haven’t before seen in anyone my age. His experience in the military has taught him control—control over his motions and emotions—but he has discovered within himself an even deeper sense of it. I imagine it’s like having your brain think for you.

“Do you find other dancers have similar feelings?” I asked.

“It is a gift to dance,” he said. “All dancers know this. To be able to express yourself is a gift. You have to share a piece of yourself when you dance in front of a crowd, or paint, or play music. But dancing is unique because there is only one instrument: the body. And very few rules.”

At this moment, writing suddenly seemed plagued with rules. Rules are everywhere. The Singapore army must have plenty of rules. I commented aloud on Wayne’s bravery.

“I often have dreams I am falling,” he said. “They, like my other dreams, teach me before I experience it what falling feels like. I simply pray and wake up. I know what falling feels like because I have dreamed it; therefore I don’t fear it. My dreams are telling me that I will fall someday, which is what happens to all dancers once in a while. But I’ll let my body take care of it and I will get up.”

I heard the class descending the staircase. Someone flung open a door and a crowd rushed past. Everyone was eager to get to the next place in his or her life. Wayne stood up. I noticed he was still barefoot.

“More often than not,” he said, “I dream that I am flying.”

Hello! I just would like to give you a huge thumbs upward for this amazing tips you have here on this particular text. I will be coming back again to your blogs for more soon.