Image from web.

How does our memory define us? It’s hardly easy to explain and understand the meaning of memories in a few hour-long sessions, but speakers at the Memory Across Disciplines symposium tackled the question by presenting insights ranging from specific psychological explanations to much more abstract connections to memory through dance and movement.

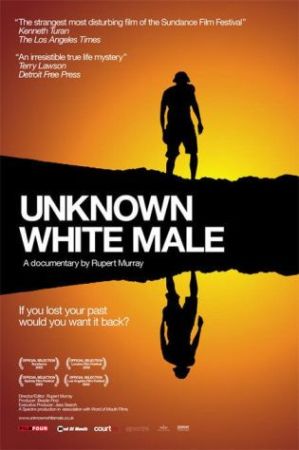

The event began on the evening of Thursday, February 3, with a screening of Unknown White Male, a documentary about Doug Bruce, a 35-year-old man who wakes up on a subway in New York City to find all of the memories from his life have vanished. The movie was an interesting way to begin thinking about the impact that memories have on our personality and identity in general. Between psychedelic clips of flashing colors and images of city streets reflecting Bruce’s lost memories, I watched as he adjusted to his new life, meeting his father for the “first time” and getting a tour of his hometown of London. The movie approached the issue in a similar way to the symposium, interviewing both psychologists and philosophers who gave their own opinions on Bruce’s condition. The movie ended on the more philosophical side of things with Bruce standing on the balcony of his apartment asking the camera, “If we are only made up of memories, then who are we, really?”

The next morning, Mark Freeman a the psychology professor at the College of the Holy Cross, began the symposium by summarizing the idea of memory on a large scale. Jefferson Singer, a psychology professor here at Conn, presented a paper that explained that one of the most important aspects of memory in psychology is “self-defining memories.” He gave examples of his own patients to illustrate the importance of looking back on seemingly insignificant memories to understand current personality traits. Additional papers were presented by seniors Emily Lake, Aili Weeks, and Mary Gover.

Although all of the presentations were informative and it was clear that the presenters had spent a huge amount of time pondering the idea of memory, the transition between a presentation on psychological concepts such as performative self and external narrative and a paper on human rights in mental hospitals was a rather difficult one to make.

In the afternoon, Conn faculty from several disciplines participated in a panel discussion, connecting their fields of research to the idea of memory. Slavic studies professor Andrea Lanoux discussed one of her projects that consisted of speaking with Russian youths about the fall of the Soviet Union, a monumental event that happened when they were very young. She found that their own memories were overridden by those of the older generation and that the event means surprisingly little to them in the present. Professor Courtney Baker of the Department of Literatures in English talked about her research into images of black suffering and death and their role in constructing American cultural memory. Her colleague Lina Wilder, whose book Shakespeare’s Memory Theater was just published by Cambridge University Press, talked about the role of memory in Hamlet.

As I listened to each presentation, I found myself wondering how this would come together in the end and whether these topics could really be related. David Kim and David Dorfman’s joint presentation on movement was definitely a highlight of the symposium. The audience was asked multiple times to stand and create some sort of movement that would later have to be remembered and repeated. “Movement can unlock so many individual experiences and connect people,” Dorfman said, as the audience (myself included) awkwardly swayed and jumped, trying to recall our own muscle memories. The idea of muscle memory and its connection to our personal psychological memories was an unexpected addition to the conversation.

The last presentation was given by Negar Mottahdeh, who spoke about the 2009 protests in Iran against President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. She explained that much of the spirit of these protests were directly influenced by the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The chants and songs were adaptations of those that came thirty years earlier.

When the question and answer session began, someone immediately asked what we had all been thinking, “So how can we connect all of this?” Many of the speakers offered their own answers; Dorfman said, “What we all want from memory is truth. There is a human desire to remember.” The fact is that it’s impossible to find one theme of the symposium, but it did give the rare opportunity to see professors and students from a huge range of disciplines offer their thoughts on the importance of memory on personal identity and let us attendees ponder the topic on our own. •

Additional reporting by Jazmine Hughes and Meaghan Kelley.