A pronoun is a stand-in for something specific, something definable. A pronoun is a placeholder for something typically already identified, to which one later alludes. Charles ate an apple. He found it on the ground. “He” is Charles, and “it” is the apple.

Over the course of the past four years, at a point indistinguishable even in hindsight, “home” became a pronoun. It, “home,” no longer refers exclusively to the town in which I grew up, nor to the driveway where I park my car every November, December, March, and May, nor to the backyard I sledded down as a child, nor to the bedroom I cried in as a teenager.

More so than it alludes to a physical place, the word suggests a sense of stasis and belonging, of balance and permanence—one that’s shifted from that town, that house, that backyard, and that bedroom to something newer, and yet somehow infinitely more familiar. Little by little, Here and Now supersede the “from” in “Where are you from?” and, almost all of a sudden, the question seems starkly, startlingly irrelevant.

More relevant questions at this stage of my life include, but are not limited to: “Where do you live?” “Where do you go to school?” “What do you want to do when you graduate?” The present is a climbable staircase, while the past often seems a dusty crawlspace. By which I mean I don’t think a lot about home.

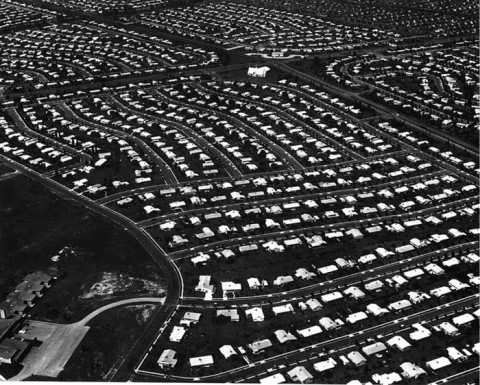

Growing up, my family moved around a fair amount. I “grew up,” whatever that means, between Maine, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Connecticut. Between kindergarten and fifth grade I attended five different schools, and grades six through twelve would see me at three more. Compared to friends of mine who were born and lived eighteen years in the same house, with the same two, still-married parents, my childhood seems remarkably off-kilter; compared to the childhood experiences of other friends, I might as well be writing home to Levittown, PA.

The very instability of “home”—that it means my dorm room after last call on Tuesday bar night, that it means my mother’s house during finals, that it means every sidewalk from Freeman to Harris at the end of every vacation—speaks to the sheer relativity of my domestic center of gravity. “What dorm do you live in?” “What year are you?” “What’s your major?”—these questions I can answer. “Where’s home?” is considerably tougher.

They say no matter where you go, there you are—and how true. Here we are, and certainly we were somewhere before we were here (somewhere that led us to being here now, however circuitously), but where are we now, really? Are we home? Maybe, sometimes.