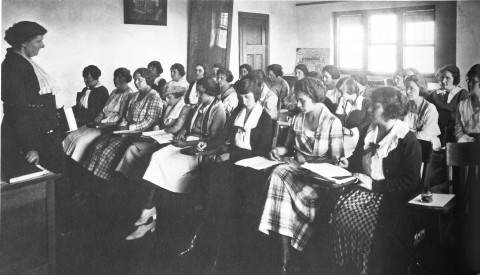

Carola Ernst (of Ernst Common Room fame) lectures to a packed classroom in Romance languages in the 1920s. Not only have classes changed (hopefully for the better), but so have attendance trends. Photo from the Conn College Archives.

Prior to 1989, each Eastern European government would organize a few pompous national parades on notable holidays each year. Every citizen above a certain age was required to attend and celebrate the genius of the communist leaders and the prosperity of his/her country. Since the authorities knew well that the people were not quite convinced of either, however, specially appointed clerks at schools and workplaces took attendance and submitted the lists of truants for punishment.

If this does not ring a bell, check the last few syllabi you received. If they are at all similar to mine, they probably have a section indicating that each absence affects your participation grade negatively, with two or more resulting in significant reductions of your overall semester grade. The logic is plain and simple: if you want to get students to do something (in this case, go to class), threaten to hit them where it hurts the most (grades) and voilà! In international relations, we define such actions as belonging to the hardcore “sticks” approach, i.e. exploiting a clear power asymmetry to coerce an actor to follow a path you have defined for them, kind of like what the U.S. army did in Vietnam and Afghanistan until leaders realized it is not sustainable in achieving any long-term goals.

The immediate alternative is, of course, the “carrots” approach, which is IR jargon for providing attractive benefits that incentivize an actor to take a set of actions without resorting to or threatening to use force. From psychology (and the name B.F. Skinner comes to mind), we know that positive reinforcement is much more successful in altering behavior than punishment, which tends to have only temporary effects. In other words, it might be the case that providing students who attend all classes in a semester with some form of extra credit might be more effective in pursuing the goal of universal student presence in classes. Even if extra credit is not an option, we should be open to a system in which attendance is rewarded.

All students of international relations, however, know that there is a third way, which often turns out to be the star of foreign policy. In a 1990 book, Joseph Nye, a Harvard doyen of IR theory and a former Undersecretary of Defense, coined the term “soft power” to refer to the ability of countries and leaders to obtain desirable results through persuasion and attraction (through upholding ideals, demonstrating exemplary behavior or presenting a compelling story) without the usage of either “carrots” or “sticks.” In other words, the beauty of “soft power” lies within its ability to make it one’s choice to follow a certain course of action that another actor finds advantageous—in our case, to go to class regularly because we want to and not because we have to.

Such an approach relies on a professor’s ability to convince students that classes are indeed valuable and indispensable. This could be done in two ways. The first (and not ideal) one would be to integrate class discussions into exams and assessments, making it impossible for students to attain high grades on exams if they have not participated in classroom discussions. Indeed, if class time does little more than summarize a set of readings (which everyone can do on their own), students can ace assessments without having attended many classes and there is absolutely no reason to punish them for having found alternative ways to enrich themselves during class time. The second and far superior alternative would be to make classes fascinating, engaging and enlightening, not just by going beyond the readings but also by connecting them to what truly concerns us in the twenty-first century. Achieving high student turnout this way requires a lot of preparation, immense knowledge and a remarkable pedagogic talent, but also creates the type of educational process in which we all aspire to participate.

Luckily, we do have professors with captivating teaching styles who succeed at convincing us that missing classes is unwise due to the high level of insight and knowledge they provide. (By the way, they are usually also the least stringent about attendance policy because they are comfortable in their ability to attract students in a different way.) At the same time, however, the current attendance policy removes the incentive for all professors to measure up to these high standards; after all, it is much simpler to have the threat of lowering grades hang menacingly like a sword of Damocles above students’ heads. Doing the latter harms the learning process because every student can attest that being in class is one thing, but being truly engaged (especially in the information age) is something completely different. Finally, the attendance policy prevents students from being able to practice making real-life decisions based on what they find more valuable by having us respond to simple incentives.

I have to say that I (just like virtually all members of the Connecticut College community) recognize the value of classes in the long run. What I do believe, however, is that the way we convey the message of their importance needs substantial revision. Dwight D. Eisenhower once said, “Leadership is the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because he/she wants to do it.” I would rather have my professors remind me of his words, as opposed to the roll calls with which my parents had to deal. Wouldn’t we all? •