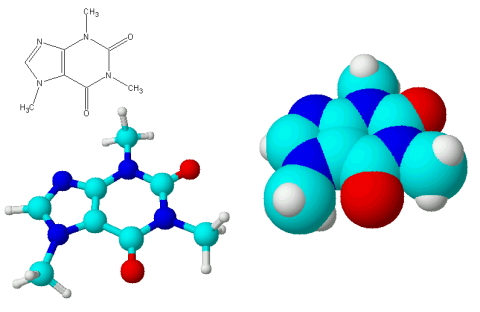

Something most of us are familiar with: caffeine. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

We’re all in college to achieve a higher education and challenge ourselves. With that comes a hard truth: sometimes we have to take difficult classes. We’ve all had those rip-our-hair-out-of-our-scalp, no-sleep-for-three-days-straight, crying-at-random-times-throughout-the-day-because-we’re-sleep-deprived-and-overwhelmed-with-life classes. Based on students’ opinions, three of the most difficult classes offered at Connecticut College are Organic Chemistry with Professor Timo Ovaska, Metaphysics with Chair of the Department of Philosophy Andrew Pessin and Introduction to Finnegans Wake with Professor John Gordon.

Arguably one of the most difficult classes at Conn is Organic Chemistry, which deals with carbon-based molecules. Rarely do I hear the word “orgo” without a shudder following it.

“It’s a class that takes over your life, almost literally,” according to chemistry student Sarah Spiegel ’11. “Every single night when I closed my eyes, I saw molecules. I dreamt about it. If you can’t get a problem, it drives you crazy.”

One of the main challenges of organic chemistry is the ability to view material in a three-dimensional manner. According to Spiegel, “Unless you’ve taken a sculpture class, you haven’t had to think like that before in 3D. You need to go inside the molecules to visualize them and be able to tell them apart.” While taking tests, Spiegel said she often closes her eyes and tries to figure out “what the hell is going on inside the molecules.”

Aside from the challenging material, organic chemistry becomes difficult when students attempt to memorize the information, rather than learn how to do it.

“Students who find it difficult are the ones who try to memorize it. There are a lot of reactions—hundreds—that one can’t memorize. They need to understand things at a molecular level,” said Ovaska.

With some subjects, each chapter focuses on a different aspect of the topic, but in organic chemistry, material is cumulative, which adds another level of difficulty.

“With orgo, everything builds upon previous material. You couldn’t do the stuff we’re doing today if you don’t have a handle on the previous material,” said Ovaska.

Spiegel echoed this idea, saying, “You cannot cram for orgo the night before a test. Even the smartest people have to work their asses off.”

The class certainly requires learning a lot of material, but the difficulty of the class also “has to do with whether or not people are interested in the topic,” said Ovaska, adding, “if you don’t like it, it becomes harder for that reason. If you’re into it, and some people are, believe it or not, it becomes easier and it does make sense to a lot of people.”

“It’s a different way of thinking and takes a really long time to get used to. It never gets easier, never lets up. There’s really intense problem solving, but it’s really cool and I really like it,” said Spiegel.

Another class that makes students think outside the box is Metaphysics. As Pessin tried to explain to me, metaphysics is “an incredibly broad” topic, which deals with the ideas of realism versus antirealism. Realism is the view that “features and properties in the world are independent of human feeling/cognition” and antirealism is dependent on human feeling/cognition. (At least, I’m pretty sure that’s what he said).

It’s a reality that the material of the course is pretty difficult. Said David Liakos ’12, “The course covers a lot of really tough contemporary philosophical problems—about aesthetics, ethics, science, time and other issues. What the course is dealing with is nothing less than the question of the objectivity of reality. The philosophical questions we were dealing with made your head spin, but they were provocative and deeply interesting.”

According to Pessin, the primary goal of the class is “to develop your own thoughts in regards to material studied, to master the thoughts of the people you’re reading about and to be able to exposit material, engage in it and say something original about it.” He added, “In the latter part of the course, [students are] challenging really basic intuitions and assumptions. It’s hard to dislodge basic intuitions, but the arguments really push you in that direction.”

Pessin believes that his workload is not heavier than any other class—just challenging. In addition to a formal class presentation, seven mini-papers and a final paper, Pessin has his students complete regular quizzes on Moodle, which are apparently a pain in the ass.

“I’m a big fan of the quizzes, but students grumble about them. They think they’re unfair. I don’t want them to be unfair, so they’re not…They’re multiple choice, so it’s really tough because the given questions and answers are ambiguous, especially if [the students] understand things differently from the professor,” said Pessin.

Liakos vouched for the workload, adding, “In addition to the difficulty of the questions we were dealing with, the work was also demanding…Pessin made us write a weekly mini-paper on these problems, and he’s quite demanding in terms of the quality he expects. It’s not easy to deal meaningfully with these issues in less than a page.”

As for the third course, how would you react if I wrote the rest of the article like this: “It darkles, (tinct, tint) all this our funnaminal world. Yon marshpond by ruodmark verge is visited by the tide. Alvemmarea! We are circumveiloped by obscuritads. Man and belves frieren. There is a wish on them to be not doing or anything. Or just for rugs. Zoo koud. Drr, deff, coal lay on and, pzz, call us pyrress!”?

You’d probably grow frustrated and stop reading it, right? You’d Google Klingon only to realize this isn’t Klingon. Well, imagine taking an entire course in which the only object of study is a six hundred twenty-eight-page book, all of it written like the excerpt above (which describes night falling at a zoo, by the way). The book is too dense to be read in its entirety in one semester, hence the course’s official title, Introduction to Finnegans Wake.

The class is dedicated solely to reading and analyzing (and maybe crying over) James Joyce’s last work, Finnegans Wake, an incredibly difficult read because of its language. Joyce uses complex portmanteau words that include multilingual puns, historical and autobiographical references and onomatopoeia to pack maximum meaning into every single syllable of every word. Take the first word in the novel for example, “riverrun.” It simultaneously suggests “riverain” (pertaining to a river), “rive” (to tear apart), “river” (French for “to fasten”) all while describing Dublin’s river Liffey. As if that weren’t enough, the last sentence of the book circuitously runs into the first sentence, creating an endless loop, a sort of literary Möbius strip, as Gordon has called it. Joyce himself referred to it (in the book itself) as his “book of Doublends Jined,” which not only means “double ends joined,” but “Dublin’s giant,” as, among other things, it’s about a mythical Irish giant buried under Dublin.

The book is so difficult that lecturing on it is nearly impossible; class time is exclusively dedicated to students asking questions about specific words, sentences or pages that they couldn’t crack themselves.

“As a teacher, I’m not a task master. I can’t get around the fact that the subject matter is very difficult, but the great thing [about Finnegans Wake] is it’s not nonsense. The more you read it, it becomes clear. It’s a riddle in a sense and uncovering it is fun,” said Gordon, who has taught the class a handful of times at Conn. “I’ve done a lot of work on the book, invested a lot of time in it. I think it would be wasteful not teaching the course every now and then.”

The structure of the course itself is “really standard” and has a “regular workload,” according to Gordon. Students must write two papers, give two presentations and complete one final exam. “It’s not the structure of class that makes it hard to deal with; it’s just the content of the book,” he added.

Students who take the class are “self-selective and can take on a challenge,” said Gordon, adding, “Students grin and bear it. There are certain parts of the book where the author addresses the audience, as if to ask ‘are you confused?’, but I haven’t had anyone panic yet.”

The one unifying factor between the three classes is that students (for the most part) willingly sign up for them, not as some form of sadistic punishment, but because they are genuinely interested in the subject matter and love a good challenge. So kudos to anyone who has taken or plans to take any of these classes. •