Digital image. All New York Tours. Web. 12 Apr. 2011. <http://www.allnewyorktours.com/body.asp?tour=NYC-ADM12&page=TourDetails>.

In one of many cramped Brooklyn two-bedrooms on 16th Street, Maria and her parents are readying themselves for another day. Their apartment consists of a narrow hallway like a train track which runs past the bathroom and bedrooms and eventually turns a corner, spilling into the kitchen. It is the best Maria’s parents could afford, but they are saving for something better, closer to Prospect Park and the Beansprouts Nursery School.

Maria sits at the kitchen table on a booster seat. For the past year she has been trying to climb onto the wooden chairs, wailing when one of her parents grips her underarms and lifts her to the high chair. Her head is straining toward a bowl of Cinnamon Toast Crunch. Maria’s mother Katka enters the room barely making a sound, dancer’s feet at home as much as they are at work. She wears black leggings over her leotard, which pale to grey next to the deep hue of her hair. Maria watches her pull a long woolen sweater from a chair and swing it around her shoulders.

Katka peers at her daughter, who brings a spoon piled high with sugar-coated squares to her mouth. “Drew,” Katka calls, snatching the bowl from under her daughter’s chin.

Drew emerges from the bedroom, buttoning his shirt. His hair is still fluffed, his face still creased from the pillow. He showers at night. He is about a foot taller than his wife. He looks at her, then drops his gaze to the bowl. “Problem?”

“If you’d like to pay for Maria to get some more cavities filled, then, no, I guess there isn’t a problem.”

Instead of listening to her, Drew studies the layers of tape on the floor separating the kitchen and living room. Really, there was already a division created by the border of oak wood and linoleum, but Katka had insisted on the tape. It is brown and matches the wood, and she’d had Drew spend a few hours pulling strip after strip of the stuff, pressing them down on top of each other to create a little ridge.

Drew takes the bowl from her, steps into the kitchen and sets it down in front of Maria. “We’ll just have to make sure she brushes and flosses like a pro. We’ll practice tonight. Right, Maple?”

“Yes, Pancake,” Maria answers and dips her spoon in again.

Maria named her family after her favorite breakfast three weeks ago when she asked what made syrup so sweet. Her father answered, Maple, it’s like you, it’s even got the first letter of your name. Maria pointed her syrupy fork at her father, dubbing him Pancake because of his squishy tummy. Katka was left with Syrup to complete the trio.

“See?” Drew says, looking at his wife over his shoulder.

Katka raises one black eyebrow into a pointed accent, like the kind you see in music or in foreign languages. She tightens her ponytail, unconvinced.

“Pancake,” Maria says, mouth full. A few partially chewed bits of cereal spew from her lips and land in the center of the table.

Laughing, Drew grabs the sponge from the sink. He can’t help laughing. No matter how many dishes his daughter mistakenly tosses into the garbage bin or guitar strings she uses to make necklaces. He wipes down the table and glances at Maria, whose cheeks are puffed out like a blowfish. She is struggling to swallow.

“Take smaller bites,” he says. “Don’t talk if you think something might fly out.”

“Can I have hot chocolate?” Maria says after gulping down the cereal.

“No,” her mother replies before Drew can answer. “That’s enough sugar for you. You can have water if you’re thirsty.”

Drew ruffles his daughter’s hair and presses his lips to the zigzagging part that divides her thick brown curls. Then he steps over the tape bump and moves toward the door. Katka trails after him and waits while he shoves his feet into his shoes. They are dull and scuffed. Putting them on would not be so difficult if he could take the time to untie them first. She suspects he has left them double-knotted since the first day he wore them, two-and-a-half years ago. She forces a smile as he turns and bends to kiss her.

“Why am I Syrup?” she asks.

“Why not? You’re sticky, you’re glue to hold us together, when I sniff you I get high.”

“No, really. I want to know.”

Drew shakes his head. “Ask Maria, she’s the one who gave us the names. We could switch, if you want. She probably wouldn’t mind. She’ll want to stay Maple, though.”

“I’m not asking anyone to switch,” she says.

He gives her a quick kiss on her forehead, and then he is off. Katka goes into the kitchen to fix Maria her lunch. Baby carrot sticks. Fruit Punch Minute Maid. Peanut butter and strawberry jam on whole wheat. Unlike most children, Maria doesn’t mind the crust. Katka hesitates before dropping in a Chips Ahoy cookie.

***

After Maria’s seventh birthday, she begins taking dance lessons. Jazz, tap, and ballet. She has stopped referring to the family as Pancake, Maple, and Syrup. She has also stopped pulling spare strings from her father’s guitar case. Instead she sneaks into her parents’ bedroom and unzips the case, running her thumb over the strings that are stretched over frets, all the way up the neck of the instrument. When her thumb gets sore she finds Daddy and asks him to play for her.

Drew’s head is gradually being overtaken by bare skin. When Maria was still a toddler, he could comb his hair in such a way as to hide the receding hairline. His fleshy belly is becoming rounder. Katka has put him on fruit-and-veggie diets, but he keeps a rotating stash of Sour Worms, Gummy Bears, and Skittles in his guitar case. He feigns a look of child-like guilt when she catches him sneaking the sweets. He does not tell her about the tightness he sometimes feels in his chest—only sometimes, and never for any length of time. He thinks it might be the asthma he used to have as a child.

Maria envisions him as a rock-star. One evening after dinner, she asks why he doesn’t bring his guitar with him when he leaves for work. Daddy says it’s only a hobby, that his real job is the opinion editor of The Brooklyn Paper. Maria gives him a quizzical look that doesn’t seem as though it belongs on a child’s face. “But Mommy dances. At work. Can’t you play guitar at The Brooklyn Paper?”

Her father laughs. It is booming and makes his stomach jiggle. “Mommy teaches dancing. Like your teacher, Miss Wayland, only Mommy teaches older girls. NYU girls.”

“You used to teach, too,” Maria says. She remembers the few grungy teenagers who would stop by the apartment, setting guitars on their laps that were scratched and dirty and much less impressive than her father’s Gibson.

“Would help if he still did,” Katka says from the kitchen table. She is scraping the bottom of a yogurt container with a spoon.

“Why’d you stop?” Maria asks.

“When I taught it didn’t leave me much time to practice or compose, or play with you,” her father says, and he gathers her in his arms and spins around a few times. Maria screeches as he spins faster, a dimple creasing her right cheek, but he has to stop after the third time. Maria is heavier now.

“Can we go to the playground?” she asks.

“Not tonight,” Katka says. “It’s almost time for bed, and you just had your bath.”

“Please? Just for a little while?”

Drew looks at his wife. “We’ll just go on the swings. We can be back by bedtime.”

“No.” Katka slams down the empty yogurt container.

“Come on, just fifteen minutes on the swings,” Drew says, pulling Maria’s windbreaker from the peg by the door. “It’ll tire her out and she’ll go right to sleep as soon as we get back.”

Katka is gliding toward them, her face angry, her movements fluid and graceful. “Did you hear me?”

“But Daddy wants to play with me,” Maria says. “You can come too.”

“We can go tomorrow, Maria,” Katka says. She takes Maria’s jacket from Drew and hangs it up again. “Why don’t you go pick out some books for us to read you before bed.”

Maria retreats into her bedroom and leaves her parents staring each other down.

“Let the kid live a little, Kati.” In Russia, this is what her mother had called her, and Drew pronounces it correctly instead of slipping into the hollow, biting “a” sound that Americans tend to use.

“I think we have a different idea of what living is,” Katka says.

Maria staggers toward them with a large stack of books in her arms. “Can we read these?”

Drew hides a smile. Katka ignores her and steps closer to her husband, speaking in low, sharp tones. “You want to teach her that she can have whatever she wants, whenever she wants?”

The tower of books in Maria’s arms wobbles. “Mommy, Daddy. I’m ready.”

“She’s going on a swing, she’s not getting a Ferrari,” Drew says.

“Well, she’s not going on a swing tonight.”

“Yes,” Drew says, “we heard you the first time.”

Maria takes another step and the books tip and clatter to the floor. Her parents bend to scoop them up, and then they head toward Maria’s bedroom.

Maria bounces into bed. “Mommy, take off your slippers—there’s room for you.”

“That’s all right,” Katka says. “You stay nice and warm and I’ll sit here so you can see the pictures better.”

Maria watches the slight movement beneath the maroon polyester of her mother’s slippers, a wriggling of the toes she has never seen. She should have known better than to ask; her mother never goes around without something on her feet. Bad circulation, Katka has always explained. For some reason, Maria feels this is less than the truth. Katka tucks Maria in, first pulling up the sky-and-cloud patterned sheet, then the patchwork quilt which Katka’s mother had made for her their last Christmas in Russia. Each square depicts a different scene from a Russian fairy tale, and sometimes Katka tells those stories instead of reading the children’s books. Her husband enjoys them as much as her daughter does, but tonight she is not in the mood. Drew opens up The Cat in the Hat. They take turns reading, and Maria drifts off to sleep.

Drew rolls into bed with his hair still wet from the shower. Katka is stretching on a yoga mat beside the bed. She lies down beside him and says goodnight. He says nothing, thinks about apologizing, then thinks about striking up the argument again and this time winning it. He wonders if he could—he’s never tried it. He looks over, and she is asleep and has begun her ritual thrashing around, tangling the blankets about her. Drew turns onto his side and watches, fascinated. He wonders what she is dreaming. He wonders if maybe her restless, clumsy sleep is her way of letting loose after a day of holding herself tight and upright. She will rise before the sun and go for a quick jog, shower, and eat breakfast before he wakes. She is unaware of the way she grunts and snores like an old man and flings her body in meaningless contortions while she sleeps. Part of him wants to let her in on the secret. The closest he has come to telling her is calling her a bed-hog, to which she always gives a perplexed, dismissive laugh. Tomorrow he will tell her. He will prove it, if he has to, if she refuses to believe him; he could videotape them sleeping. He tries to fold himself around her, but only manages to secure his hands at her waist. One of her arms flops over his face, covering his mouth. He feels laughter escaping him in small, short breaths through his nose.

***

Maria wakes up with one arm hanging off the side of the bed. She can’t feel it. This happens to her sometimes, and her mother reminds her that if she slept straight-up-and-down it wouldn’t happen. Daddy usually agrees, and asks her later in a whisper, “Would you like your mom to show you how it’s done?” Maria giggles, though it will be a few years yet before she understands what he meant. She hears her mother’s voice now, muffled through the walls. She has to lift her arm with her free hand and drop it a few times so that it clunks down on the mattress and tingles back to life. Groggily, she makes her way down the hall. She finds her mother kneeling on the bed next to her father, talking into her cell phone. Her mother’s words are quick, too quick, and occasionally Maria hears things that sound like the names and places in Russian fairy tales, mixed with the rapid English.

The only other time Maria has heard Russian slip into her mother’s speech was when her parents had come home late one night after saying good-bye to Grandma. That night, her mother had shuffled down the train track hallway, eyes wider than usual, and redder. Her father shoved some bills into the sitter’s hands and pushed her out the door. Maria watched her father embrace her mother, but it was as if Katka hadn’t noticed; she kept moving forward. She was murmuring something about the doctor and filth and lies and infection and her mother’s knees and then started shrieking, and that’s when Maria heard the Russian that was not a fairy tale.

Somehow her father is able to sleep through the noise, Maria can’t imagine how. By this time of morning her mother should be out running, and Maria watching cartoons on the living room couch. Sometimes Daddy would be watching with her, or playing his guitar before getting ready for work. This is the first time Maria has seen her mother crying like one of the children at school. Her mother is folding in on herself. She looks small. She looks like she might be cold. Maria goes back to her room and takes her quilt off her bed. She drags it to her parents’ room and climbs onto the bed next to her mother. Holding the blanket, Maria reaches both hands up and tries to cover her mother’s shoulders so she will stop shivering. The blanket slips, and Maria tries again. Her mother flips the phone shut and drops it onto a pillow. She curls into a ball and rests her head on her husband’s chest.

At last Maria can drape the blanket over her. “Did you have a bad dream, Mommy?”

Her mother doesn’t answer.

“What’s wrong with Daddy?”

Maria stays there until her mother gets up to answer the door. Two men carrying what looks like a narrow bed with straps walk into her parents’ bedroom.

“Are you doctors?” Maria calls out to them. She feels her limbs shaking and leans against her mother, afraid she will fall. “What’s wrong with my Daddy? Can you help him?”

Katka pulls Maria away and tells her to sit in the living room. Instead Maria stands and watches as they approach her parents’ bed. Katka draws her daughter toward her before Maria can see the men cutting off her father’s t-shirt. She whispers fast, deep Russian that Maria can’t understand but it soothes her anyway. Then her mother’s hands cover Maria’s ears to muffle the sounds of the apartment. Maria thinks she hears a mechanical whirring, a low voice, and something thump on the bed. Katka’s fingers press more firmly into Maria’s ears and she can’t hear anything more. In a few moments, Katka takes Maria by the hand and together they follow the men outside and into an ambulance. The adults’ voices blur together into a buzz, and Maria gazes at her father, who now has a strange plastic tube running beneath his nose. He has auburn fuzz on the lower half of his face which he should shave off before going to work.

Katka leaves Maria with a nurse in the waiting room of the New York Methodist Hospital. Maria swings her feet back and forth, watching her grey bunny slippers that used to be white. When the nurse leaves her for a moment to help an elderly woman with a walker, Maria slips away and walks down the hallway where she saw them take her father. She finds him at the end of the hallway in a high hospital bed with her mother standing beside him. He is still sleeping. The blips of the machines by his bed do not sound like music. Something the doctor says is making her mother shake again.

“…need your consent to carry out your husband’s wishes,” the doctor is saying. “He wanted to donate his organs…”

“Daddy,” Maria says, looking at her mother. “What happened to Daddy?”

Katka beckons to her, her face limp and weary, eyes wet. Maria comes closer and reaches up to take hold of her father’s hand. It is not quite cold, but his fingers are limp in hers.

The doctor clears his throat. “His organs could be used to save lives.”

“His organs couldn’t even sustain his own life,” Katka says. “The answer is no. Do not bring this up in front of my daughter.”

“Do you want my daddy’s heart?” Maria asks the doctor. “What if he wakes up?”

Katka takes her by the shoulders and turns her around. She bends so that her eyes are level with her daughter’s. “Maria. Daddy is…he can’t wake up, Maple.” The nickname slips without her realizing it.

The doctor leaves them, and they stay with Drew a while longer. The sun is rising as they begin walking back home, and they both turn their eyes to the cement sidewalks. Soon Maria lifts her head to gaze at her mother. Katka catches her eye and pulls her to a stop. She fishes through her purse and pulls out a small packet of Kleenex. She takes a few tissues, kneels down, and wipes at her daughter’s face, though there are fresh drippings from Maria’s nose and eyes. She lets the soaked tissues fall to the ground. Then she tries to stand up. But her legs are locked and numb, her balance faulty. The soles of her feet ache in a way they haven’t for years. She may not be able to get up for a while. Katka’s hands fumble until Maria reaches down, closes them in her fingers and drops them onto her shoulders, bracing herself. Katka leans her weight on Maria’s narrow shoulders and pushes herself to her feet.

“You okay?” Maria asks.

Katka nods, and they start forward again.

Back home, Katka steps briefly into the master bedroom to grab Maria’s quilt. Maria stares at her as she walks past, into the other bedroom.

“I don’t want to sleep,” Maria says.

Katka pulls her by the arm. “You don’t have to. We’ll just rest. We’re taking the day off.”

“I don’t want to lie down, either,” Maria says, hanging back. “We might fall asleep, even if we don’t want to, and then maybe I won’t wake up or you won’t wake up—”

“We’ll wake up,” Katka says. “I promise.”

They burrow under the blankets in Maria’s bed.

***

At the funeral, Drew’s parents Emily and Greg Patton from San Diego give Katka flowers and complain about the cold, damp weather. Afterward, in the apartment, Emily keeps her mink coat on and pats Maria on the head. She embraces Katka swiftly, as though she can’t bear to touch her daughter-in-law, as though this is somehow Katka’s fault. Maria munches on some bread and squeezes her mother’s wrist, saying her stomach hurts and she needs to lie down. Katka boils water for peppermint tea and tucks her daughter in.

“Is the tea too hot?” Katka asks.

Maria is holding the mug on her chest with both hands. She breathes in the steam and shakes her head. “Smells good.”

Katka adjusts the blankets again and rests the back of her hand on her daughter’s forehead.

“I’m not sick, Mommy,” Maria says. “Don’t worry.”

Katka leans forward to kiss Maria on both cheeks. She closes her eyes, holding her face close to her daughter’s so she can feel Maria’s breath on her nose.

“Does your stomach hurt, too?”

Katka straightens up quickly, surprised, as though she’d forgotten where she was. A thin-lipped smile is all she can manage. “Keep sipping. I’m sorry about all these people, all the noise. They’ll be leaving soon, and you and I will have some peace.”

Katka returns to the group huddled in the living room, wondering whether it would be rude to ask them to leave. She is thankful for her daughter’s upset stomach because it gives her an excuse. Just then Drew’s parents swoop toward her to apologize for not being able to stay longer, they should really head back to the hotel to get some shut-eye before their early flight in the morning; their loofah business really can’t manage more than two days without them. They get to talking about loofahs. Drew has told her that, contrary to what one might expect, there is a lot of money to be had in loofahs; that his parents’ company is the biggest, most profitable loofah manufacturer in the country (“These are homegrown loofahs we’re talking about,” Greg would boast, “none of this China-India crap.”), and he, Drew, was meant to continue the business. Drew’s friends and co-workers, along with Katka’s friends, who’d insisted on preparing the cheese and vegetable-and-fruit trays, stay on to clean up. Katka begs them to take the leftovers.

***

Months later, she and Maria still expect him to stride in through the door after work, as always. His scent is still in the apartment. His clothes, his worn shoes, his guitar. Bit by bit, Katka packs him away, throwing out his older clothing, donating the newer. She keeps the shoes, leaves them tied. She knows she will get a large sum if she sells the guitar. She decides not to. She and Maria move a few blocks down, marginally closer to the park. She keeps the guitar and the shoes on the top shelf in her new closet. They are pushed toward the back, far behind her cloth and leather handbags and the belts that she never uses, but she doesn’t forget they are there.

***

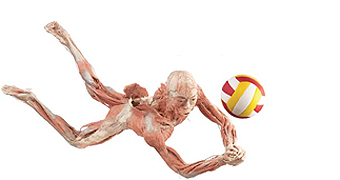

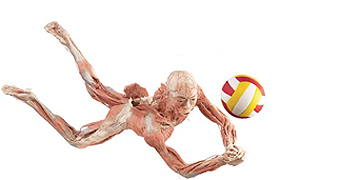

When Maria slides back on the seat, she notices the BODIES: The Exhibition posters plastered to the walls of the subway car. They display a skin-stripped man poised to deflect a volleyball. Her mother squirms next to her. The man’s red striated muscles are stretched taut, ready to snap; his eyes are empty, staring and not staring, in their sockets. He still has lips though, and a vestige of a face. The white of the skull. Maria can’t tell which is more frightening—the bones or the muscles. What’s that tuft of muscle on the bottom of his foot, where his heel was—should be? Do heels have muscles? She wriggles her toes and slips her feet out of her mismatched sandals, one washed out emerald, the other Barney purple. She crosses one leg over the other, and her skirt rides up, revealing a flash of her underpants. This morning she had been happy to find that her favorite pair of underwear, blue with yellow smiley faces, was clean and neatly folded in the top drawer. She’s proud of that pair of underpants. They have holes, but they’re still smiling.

“Marie.”

Maria wonders why her mother has started leaving off the last syllable.

“Put your feet back in their shoes where they belong,” her mother says.

Maria obeys, but not before prodding the heel of her left foot with her forefinger. The skin is rough, calloused, with a patch of dried-yellow skin where a blister used to be.

The man across from her is grinning, though he looks nothing like the bright happy faces on her underwear. She notices that his eyes are dull and unmoving, fixed straight ahead, like the man on the BODIES posters. They have no attention, no motivation, no object in view—and yet he’s smiling.

Suddenly he snaps his head to one side, thumping his skull against the wall behind him. He snaps the other way, and Maria jumps, as though she’d forgotten to be surprised the first time. He snaps back and forth in a slow, steady rhythm. His eyes do not blink. Then he stops. He is still grinning.

Maria begins to cry, near-silent sniffles at first, then full-throated sobs as he starts snapping again. Snap-bang, snap-thud: one of his snaps is always louder, she can’t tell which.

“Shh,” says her mother. “Just look away. Remember what we do with the jinglers on the street? We just look forward and keep walking.”

Her mother calls them jinglers because they often shake cups or tiny cardboard boxes of coins in people’s faces, and lots of them sing and dance, too. But the jinglers aren’t like this man. Jinglers don’t make Maria cry.

“But,” Maria says, “but, but, I don’t like it.”

“Don’t stutter.” Her mother tries to turn Maria’s head, but she resists.

“Mister,” Maria calls out. “Mister, can you please stop? Please?”

The man does stop. Now that he’s still again, she studies his shirt: ripped, stained flannel. His jeans are just as worn, and he isn’t wearing socks. She wonders if it was her underwear that made him bang his head like that—like she’d made him embarrassed or something—and this makes her feel worse.

He starts in again. The thuds are louder this time.

“Mister, don’t!”

“Keep your mouth shut,” her mother says, squeezing her daughter’s fingers tightly together.

Maria uses her free hand to swipe at the snot under her nose. “That hurts.”

The man pauses, and Maria thinks he gives a little nod. Yes. Yes, indeed, it does hurt. You are correct.

“Ow, Mom.” Maria gets free of her mother and stands up, wobbling a little and then grabbing hold of the slick pole in the center of the aisle.

“Can you hear me, uh, mister? Please don’t do that again.”

One of his dark eyes fixes on her. “Why?” he growls.

The voice shocks her. She sucks both cheeks in and holds them between her teeth, knowing this is the same as a fish-face, but for some reason it calms her and helps her think. She considers how she should answer. Finally she says, “It scares me.”

The train stops at Carroll Street and the man leaps up, grabbing hold of the same pole, about two feet above her tiny hand. Maria’s mother does a leap of her own and snatches her daughter back.

“Why can’t you listen to me?” Her mother’s breath is a hot wind in Maria’s ears. It tickles. She scrunches up her shoulders and laughs, in the way that only seven-almost-eight-year-olds can do, with tearstains still like a wet salty ribcage stretching over her face.

Then the Snap-Bang man does something odd. Something even more unexpected, if that is possible, than when he did his first Snap-Bang. He sticks out his tongue and wiggles it. It is purple and spotted and not very pleasant-looking, but it makes Maria laugh even harder. And then the man is gone, pushing past people who are trying to enter the train. Maria wonders if he’s giving them the funny face, too.

Once home, Katka puts away the Capezio ballet slippers she has just bought for Maria. Maria goes to wash her hands and then sits down next to her mother on the living room couch. Their new apartment is more open, with a dining area off of the kitchen. Maria looks at the novel her mother has in her lap, but the words are small and unfamiliar, with strange accents and letters she thinks must be Russian.

“What’s the story about, Mom? Can you read it to me?”

Katka glances at her, then snatches one of Maria’s hands. She closes the book and leads Maria back to the bathroom.

“How many times do I tell you, wash like this.” Her mother takes both of Maria’s hands between her own and scrubs vigorously. The soap is the antibacterial kind with tiny beads in it. It reminds Maria of the tongue of her friend Heather’s cat.

Maria misses the way her father used to squirt out bubbles from the dish soap bottle in the kitchen while cleaning up from dinner. She is about to ask her mother if she remembers, but Katka finishes, leaving Maria to dry her hands.

Maria reenters the living room and pulls one of her books from the basket that is kept on the lowest shelf along the wall. Many of her books are from her grandmother, though she only remembers unwrapping the Berenstein Bears on her third birthday; it was the last book Grandma gave her, before her parents had to tell Grandma good-bye. Maria curls up in an armchair and opens her book, but pauses to study her mother. She looks at the black hair, slightly frizzed and curly. In school, Maria learned that black is all the colors, and she thinks she can see some reds, blues, and purples in her mother’s hair. She stares at the tight, serious set of her mother’s jaw and the way her eyebrows seem to be naturally frowning. Maria tries to purse her lips in imitation, and then she turns her attention to The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. This is one of the lengthiest books she has ever read, and her English teacher Ms. Jameson has warned her that it is a little too difficult for someone her age. Maria likes it anyway, and she has learned how to use a dictionary to look up the long or strange words she hasn’t seen before. She would like to read her mother’s books someday. They are heavy and thick and the print is so small—there must be so many stories inside. And in Russian! If her mother would teach her she could borrow one of those big books and show it to Ms. Jameson.

Before dinner, Katka rolls out her yoga mat over the Oriental rug and begins stretching. Maria folds the corner of a page and sets down her book.

“Mommy, are we going to dance?”

“We have to stretch first.”

Katka moves her body from child’s pose to locust to upward-facing-dog. Maria removes her socks, though her mother has not taken off her own. Maria has never seen her mother’s bare feet; when she was younger she believed that women were not allowed to uncover their feet, until she went to the pool with Heather’s family and saw plenty of barefoot girls and women. Maria’s mother had refused to go along. She never learned to swim, she’d said, and the smell of chlorine makes her ill.

On the floor, Maria copies her mother’s motions as best as she can. When they do the hamstring stretch, Katka peeks out at Maria from beneath her arms and smiles at her daughter’s attempt to grab one foot with one arm arching over her head. Katka then raises herself into a headstand with her upper arms on the mat balancing her weight.

“Wow,” Maria says. She hasn’t seen this one before.

Her mother’s body is perfectly straight and does not tremble or waver. It would appear effortless, were it not for the look of stern concentration on her face. As Katka’s cheeks start to color from the blood draining down to her head, she lowers one leg to the mat and pulls herself into a forward hamstring stretch.

“Someday,” Katka says, “when you are strong enough, you’ll be able to stand on your head, too.”

They both rise and face one another. Katka instructs softly, bending to adjust Maria’s feet and legs, tapping a finger onto her back and abdomen. She does not lose patience when Maria forgets her posture.

“You’re above the ocean on a tightrope,” Katka says, poking her again between the shoulder blades. “You’re also carrying a large bowl of water. You have to be perfectly straight, perfectly balanced, otherwise you will fall. You cannot simply dump out the bowl or drink all the water because it contains freshwater, and you are not sure when it will rain again. You must walk forward like this until you reach the land and can finally rest.”

“Couldn’t I swim to shore?” Maria asks.

“Depends on how long you can swim before growing too tired. And wouldn’t you be afraid of the sharks?” Katka pushes against Maria’s shoulders and motions for her to tilt her chin up.

“Heather thinks girls who walk with their noses in the air are snobby,” Maria says. “They have—her mom said they’ve got chocolate chips on their shoulders.”

Katka laughs. “You’re dancing, not snobby. You are walking the tightrope to save your life. Good, Marie. There you go.”

“Is dancing always like this? Always on the tightrope, trying to get to safety?”

Katka turns away and fiddles with her laptop for a moment. Strings play a familiar waltz, and Katka takes her daughter’s hands and guides her about the room, 1-2-3, 1-2-3.

“Sometimes, yes,” she answers finally. “Then other times it’s like flying.”

Katka glides around the apartment with Maria, who is trying to keep up but often stumbles and steps out of time. Even so, Maria has never felt quite like this before, so weightless, lighter than air. The music stops, and Maria gives her mother a lopsided curtsy.

Maria is impatient to hear one of the Russian fairy tales before bed. Katka is taking too long with her evening yoga. Maria slides out of bed and looks in on her mother, who is sitting with her legs pin-straight, head down, arms reaching forward, fingers curved over her feet. As Katka slowly straightens up, Maria starts to back away—she is not supposed to disturb her mother while she’s doing her relaxation exercises—but then she notices her mother’s shoeless, slipperless, sockless feet. She can’t help staring. Her mother’s feet, which move so smoothly and soundlessly around the house, which carry her in pirouettes and grand jetés at the dance studio, are battered and deformed. The toenails are yellow-grey, and there are red welt-like bumps on the knuckles of her toes.

“Mom,” Maria tries to say, but her mouth is dry.

Katka looks up and frowns. “I said I’d be there in a minute.”

Sharply, she stands and puts on slippers.

“Your feet,” is all Maria can say.

Katka kneels to roll up the yoga mat.

“Your feet,” Maria repeats.

“Silly, they don’t hurt,” Katka says.

Maria draws in a breath. She feels hot water in her eyes. She doesn’t want to cry.

Katka faces her daughter again, sees the moistened eyes and fish-face. “Marie…it’s not…really, it looks much worse than it is, you know, like calluses. On your dad’s fingers, from guitar? Remember?” Katka swallows and averts her gaze.

Maria is crying silently. “Daddy’s fingers didn’t look like that,” she says, pointing disdainfully at her mother’s toes through the plush slippers.

Katka gives a weak smile, shaking her head once. “No, but they were red and sore, like my feet were, in the beginning, when I was still learning. Then the soreness goes away and you get the tough skin, and it doesn’t hurt anymore.”

Maria’s tears run faster. “Did Daddy see? Did he know what your feet looked like?”

“Of course he saw,” Katka laughs. She takes a step forward and Maria takes a step back. “Don’t cry, there’s nothing to be upset about. Here, come here.”

Maria turns and charges to her room, slamming the door. Katka hears something heavy scraping along Maria’s bedroom floor—probably the desk; the bed and dresser are both too heavy for her daughter to move by herself. She hurries over and tries the knob, but the door does not budge in its frame.

“Marie, stop this,” Katka says. “Don’t you want to hear a story?”

Maria is crying with vigor now, wet, whining sobs against the door.

“You never told me!” she wails, again and again, until the words are indistinguishable.

***

Katka has started running in the evenings because her stretches and exercises aren’t cutting it anymore. She has tried putting on Seitz, Carmen, even Disney film soundtracks and asking Maria to dance, but her daughter says she would rather read or go over to Heather’s house. Almost every night, Katka wakes to Drew running his fingers up her inner thigh, kissing her neck, whispering her name. She smiles, still in a dream-state, and her lips find his mouth and kiss him back. Every time, she wakes saying, “I love you,” sometimes in Russian, sometimes in English, sometimes a combination of the two; always, she jolts upright with her heart thumping and a yearning heat between her legs; always, she wraps her arms around herself, turns her tear-streaked face to the pillow, closing her eyes and imagining Drew’s embrace.

The sun is setting, and Katka hovers by the stairs leading up to Amy Pembrooke’s door. She can hear the faint sounds of her daughter’s and Heather’s squealing laughter. She hopes Maria has not broken or spilled anything. She hopes she has not left her there for too long.

As she steps inside, the girls stampede toward her with icing around their mouths.

“Hey, Mrs. Soldatova,” Heather says. She has been recently coached by her chocolate-smeared counterpart on the pronunciation of Maria’s full name: Maria Darya Soldatova-Patton. “Want a cupcake?”

“Heather wanted to bake,” Amy says. “And by bake, I mean stand there and dip her fingers in the batter while I’m not looking.” And then, in a lower, muffled tone: “You look a little pale. How’re you holding up?”

Amy’s caramel hair is buzz-cut like a boy’s. She has maintained this style for several years, yet Katka is surprised every time she sees it. Katka can see the soft, sympathetic sag of Amy’s face around the eyes and mouth. It is a universal expression. She remembers it from Russia, when her father died of pneumonia that winter. Since boyhood he lived his days battling one illness to the next. The best tailor—really, the only one—in Svirstroy, he’d been saving for his family’s move to America, and leaving without him had seemed like a betrayal. She remembers soppy faces from right here in Brooklyn, when the knee operation prevented her mother from reaching her fifty-first year. Her mother, Darya Soldatova, dancing legend in Russia as much as she was in the States; Professor Soldatova, she became, passing her legacy onto her daughter (who did not take Drew’s name, who is fairly certain she owes her career to Soldatova). Katka often contemplates her parents’ deaths, and she now has a third to consider. Her father’s slow, painful fading seems somehow preferable to the suddenness of the deaths she has witnessed in America. But either way, they are all just bodies now; bodies weak, infected, or indulged; breathing, gasping, then not. Either way, whether bodies fail from disease, surgery, plaque; whether these things have happened decades ago, or within the past year—the morose expressions of those who wish they could help remain the same.

Amy begins to self-consciously dig at the dried chocolate beneath her untrimmed nails. “So,” she says, “did you have a good run?”

“Yes, thank you,” Katka answers, then shakes her head at the heavily frosted cupcake Heather is holding on her palm.

“Have it, Mom,” Maria says. “Please? Heather and I decorated this one for you. No sprinkles or gummies or Reese’s pieces, don’t worry.”

Katka hesitates. She takes the cupcake by its doilied trunk and licks some of the frosting. The girls have attempted a flower design in pinks yellows and greens atop the heap of brown. “Delicious,” she says.

Heather jumps up and down. “I’ve never seen Mrs. Sodatoya eat a sweet before!”

“Solda-Tova,” Maria corrects. “I don’t think I have either.”

Katka feels obligated to finish the cupcake, though it is making her stomach turn. She tells herself to devour it, to slurp up every last dab of frosting, slide her tongue over the doily until there is not one last trace of chocolate. She accomplishes this task while Heather and Maria run off to find the paper hats they’ve made. Amy and Katka stand alone in the foyer, and when Katka finishes eating, she walks over to the kitchen and tosses the doily in the trash. She pats her lips with her fingers and returns. Amy smiles sheepishly. Her plump face is surely the saggiest Katka has seen.

Katka studies the tiny Monet replica on the wall. She hears Amy ask, “So, are you seeing someone?”

Katka snaps her head to look at her. “What?”

“I mean,” Amy says quickly. Katka’s narrowed eyes have a way of making up for her petite body. “I mean, to talk to. Someone to talk to, about….When my mother died, my father went to a guy called Dr. Warren.”

“Oh,” Katka says, exhaling. “No.”

A nervous cough-laugh issues from Amy’s throat. “Gosh, that did come out wrong, didn’t it?”

The girls re-emerge with their hats bobbing on their heads.

“Where’s the rest of the cupcake?” Maria demands, her stern expression comical beneath the hat made of purple construction paper, glitter glue, and rainbow-colored feathers and pipe-cleaners twisted into wild shapes. A red feather drifts to the floor, and Maria squats to retrieve it, keeping her head upright. She needs to let her hat dry a while longer.

“It was tasty,” Katka says.

“You finished it?” Maria says.

Katka nods.

“See, I told you she would!” Heather whispers.

“You ready to go, Marie?”

Katka thanks Amy and helps Maria into her coat. Outside, she takes Maria’s mittened hand as they walk. The air is crisp, the sky a bluish-maroon in the aftermath of the sunset.

“I’m not very tired,” Maria says in her whining voice.

“What would you like to do?”

“Can we go to the park? You always go without me.”

“I run in the park, that’s why.”

“Can we go now, though?”

“Will you go straight to bed after we get home?” Katka asks. She has to bargain with her daughter, the same way she used to do with her mother.

Maria nods, moving her entire body and not just her head, as if this will convince her mother of her sincerity.

Night is falling rapidly, and when they reach the park, Katka grips her daughter’s hand tighter. At dusk, Prospect Park is calmer than it is during daylight hours. Tonight, the autumn air is bending toward the first frost. Runners zip past; there is an elderly couple packing up a picnic in the distance; two teenagers wearing parkas and no gloves are making out against a tree. It is still, calm, though not peaceful. Katka and Maria will not go deep enough to block out the rumbling of traffic.

A low crouched figure up ahead brings Katka to a halt. Maria tries to keep walking, straining against her mother’s arm with all her might.

“Hang on, Marie. Just wait a minute.”

Keeping her eyes on what might be a raccoon, or a skunk, or a feral cat, Katka edges forward. Now it is crawling toward them. Katka thinks, instinctively, wolf, coyote, but Maria declares, “It’s a puppy!”

They both watch its slow progress. It looks like a yellow lab, but its fur is clotted with mud and grime, and there is a bald spot on its side. “It’s limping,” Maria says. “Mommy, it’s hurt.”

“It’s time to go home now.” Katka tries to steer her daughter in the opposite direction.

“It’s injured, somebody threw rocks at him, somebody beat him up and threw him in a mud puddle, look, Mommy, look, we have to help.”

“We’re leaving.”

“No!” Maria’s cry sounds like a howl. The dog freezes, eyes glistening, ears flattened back, tail drooping.

Maria struggles with her mother and twists free.

“Marie! Stop!” Katka races after her and pulls her back by the shoulders. She spins her around. “Listen to me. We have no idea what’s happened to that dog, where he’s been—he could have rabies, he could be vicious.”

“He’s not—”

“You are not going near him, understand?”

Katka feels something nudging her ankle. She looks down and it’s the dog. She lurches back, pulls Maria behind her, but the dog is whimpering and sidling away.

“We have to help,” Maria says, peeking out from behind her mother. “If we don’t, he…he’ll go to sleep and he won’t wake up—you said it doesn’t happen to everybody, but you lied, I know it does.”

“Marie—”

“It’s cold, he’s cold, see? He wants us to take care of him. Daddy would’ve.”

“Daddy’s not here,” Katka replies.

They are both looking at the dog, not speaking. Katka releases Maria, tells her not to move, and takes small steps forward. The dog watches her approach, holding its front left paw up off the grass. She stands over him, and her shadow makes him shrink away, limbs trembling. Katka can see where his ribs are; they are especially prominent where he has lost hair. Katka bends and reaches out a hand. The dog whimpers again and tries to run, but stumbles on his bad leg and falls on his side.

She extends her hand again, palm-side up, and waits. “It’s okay,” she says.

The dog lies there a while, looking at her hand, and then begins to lick his paw. Layers of fur and skin have been stripped away by a deep gash. Infection will spread soon. Katka rests her hand on his head and strokes his back. She remembers the salve her mother used to make when her feet were still hardening themselves to pointe: a mixture of canola oil, aloe vera, chamomile, and cedar leaves, very simple, very effective. Maria moves forward to kneel beside her mother, and she reaches out a tentative finger to pet the dog. He sighs and blinks. As far as Katka can tell, he has a good, strong spine and no other major injuries beyond the leg. He is just tired, hungry, thirsty, frightened, cold. His owner may have abandoned him, or abused him, or both. Perhaps he ran away. Katka unzips her fleece pullover and wraps it around the dog. He looks at her, yawns widely, and closes his eyes.

“It’s okay,” Katka says. “You’re going to be all right.”