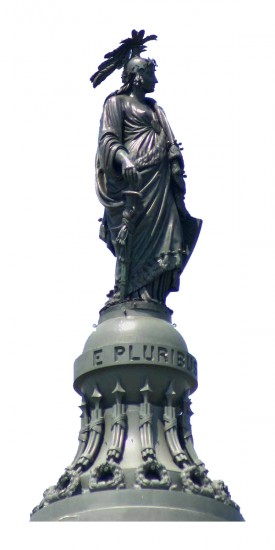

"Freedom" atop US Capitol building. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

When I go home over break, I usually spend most of my time reveling in the comfort of private bathrooms, normal-sized beds and vegetables that have not been steamed or drenched beyond recognition with mayo-based dressing. These comforts can keep me shut up in my room for days on end. But there is another reason not to leave: in my tiny suburban town, I will inevitably run into a mom, or teacher, or a former boss who will engage me in my most-rehearsed conversation.

“How’s school? What are you majoring in? What classes are you taking?”

I hate the sound of my own voice, drooling the over-spoken answers. I can’t remember what I just said and get nervous that I’m repeating myself. Usually, I rush off to an imaginary appointment for something a more responsible, more together college-aged person might be doing.

But before I can make my escape, my interrogator usually tries to find some tenuous connection between my college experience and theirs. As they tell me about their eccentric art teachers or senior pranks, their eyes take on a familiar wistful glaze and I can almost see their glory days playing across them. “Such an exciting time,” they say. “So much freedom.”

Freedom is a tricky word, especially in America. It’s also the name of Jonathan Franzen’s new book, which has become a favorite of many great Americans, including book critics, President Obama and Oprah. In the book, freedom is not all it’s cracked up to be. The characters who fight the hardest to free themselves from obligation to others end up being the most miserable. Franzen suggests that freedom does not lead to happiness. Rather, happiness is found in a sense of belonging—to a person, a community or to a cause.

If the success of Franzen’s novel is any indication, this message seems to have struck a chord with readers. It’s interesting that in a country that seems to consider its very nature to be synonymous with freedom, so many people feel conflicted about it. It is also interesting that college, a word that has the power to reduce any respectable adult into a long-winded mess of nostalgia, is similarly connected to freedom.

Over the weekend, I attended “Connecticut College in Print,” an event hosted by the Voice editorial staff featuring a panel of former editors of the school newspaper in all of its forms. They shared some of their favorite memories of working for the paper and what the role of the publication has been over the past five or six decades. What they all had in common was an apparent love of and passion for the Voice. But aside from working on something that informed and united their peers, they also loved being a part of the staff. They laughed about working late on Thursday nights, laboriously assembling the layout by hand (which used to be done in Norwich and Mystic) and staying up into the wee hours of the morning to deliver papers personally to each dorm. One editor referred to these tasks as an integral part of “the best four years of [his] life.”

The reason the Voice (formerly ConnCensus or Satyagraha [Sanskrit for “truth-force”] among others) was so valuable was the sense of belonging it gave them. They all slipped into that familiar nostalgic stupor as they told us about the school’s mammoth first typesetting machine and working with the first boys allowed to attend their beloved Conn College. After living at home for most of one’s life, college is exponentially freer. But that’s not what we love about it. We all love the niches of obligation that we find here—be they with the newspaper, an a cappella group or a sports team.

Freedom is something that most of us have the luxury of ignoring. Living in America, and particularly at a small, liberal arts school in the Northeast, we take for granted that we’re free. It is interesting to consider, however, that most of the enjoyment we get out of our tiny, loving community comes from the restriction of our freedoms. Our school influences, if it does not determine, what we learn, where we live, eat and study, and how we spend our free time. What the school doesn’t schedule for us we schedule for ourselves: meetings with clubs, teams and organizations that rely on us, make us committed, responsible and tied down.

Over the weekend, I went to a party in Freeman. Between the densely packed bodies spilling out into the hall, I caught glimpses of American flags on the walls of two different dorm rooms. I asked the boy who lived in one of the rooms why they were so patriotic.

“It’s Freeman,” he said. “Freedom!” •