“Don’t be alarmed if someone confronts you with the question, ‘Do you own a gun?’”, she said. “Also, don’t take any attacks on American foreign policy personally.” Several other IFSA-Butler staff members confront a group of about forty American students about the seemingly familiar unfamiliarity we might be confronted with during our brief stint in the British Isles. “Oh, and don’t be surprised if people approach you randomly – we really dig your accent, you know, it reminds us of Hollywood.” She adds, “Hey, don’t think we can’t tell you apart in a crowd, your perfectly aligned teeth are a dead giveaway – not to mention the object of our envious fascination.” She is beaming. Her smile reveals her non-American teeth and exemplifies her statement. I am part of the group, and my positioning strikes me as interesting. I understand why we are addressed the way we are, and yet none of her comments address or concern me. My views on American foreign policy have a large subject-of-the-empire bias, I’ll probably never own a gun, my accent is decidedly not Hollywood (no, not even the caricatured funny talking Indian male), and I haven’t seen a dentist in the last ten years. I look around the room and people are smiling, nodding and listening, for the most part, engaged. The Butler staff do their job well. I smile, for my own reasons. My orientation will start in the streets.

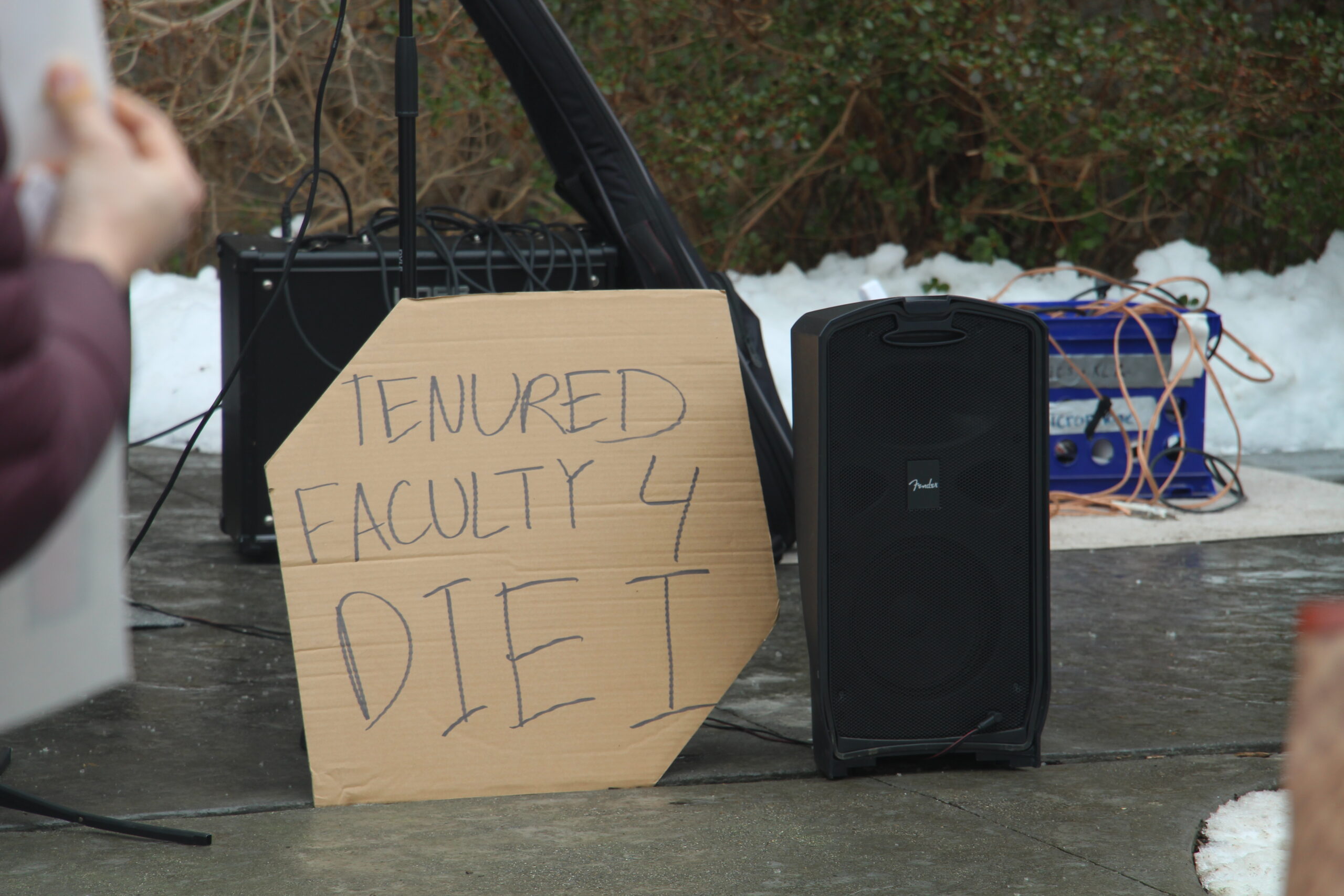

The IFSA staff’s attempts to warn us of the unassuming foreignness that we were about to encounter outside the pamphlet-aided, smiley-faced, bill-free three days we spent in Central London’s St. Giles hotel were not without reason. I study at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), an institution which is a bit of a peculiarity in the larger University of London scene (what with King’s, LSE, UCL, Birkbeck et al). for not only is it a specialist institution (namely so), it has a strange appeal. Those who know a little about it aside its name sing its praises. Those who don’t think of it as an ancillary building of the University of London. Which it is. The point being, this little institution thwarts my perception of most things academic. The international student population is an overwhelming 60% or over, and I have yet to meet someone who is monolingual at SOAS. Protests, student mobilisation (with a marked ‘S’) and union (SGA equivalent) activity is much more prominent – if partaking in nationwide student union strikes to demand more investment in specialized humanities courses; or a building takeover to demand a statement from the Uni president condemning the Lebanon war of 2006 is any estimation.

Inside the academy, the nature of knowledge production and dissemination is more specialized than a typical liberal arts framework – most people are well aware of the intricacies of their particular subject area, complete a bachelors degree and a master’s one in four years, though the interdisciplinary nature of liberal arts education and the neuronal inter-linkages resulting from it at Conn are aspects that are missed. More broadly, aspects that I particularly relish about being in London include free entry to most museums, the humongous public libraries, reading by the Thames, a few dozen places to choose from for live music everyday, the diverse bookshops in central London, some of the best food in the world (from around the world), double-decker bus rides after a long hectic day and finally the wholesome pints of delicious lager (no, Coors, Keystone and Bud Light don’t qualify as beer here) to end the day.

While the plethora of exhilarating stimuli never ceases to engage me, I take some quiet moments of reflection by my kitchen window, sipping chai, exploring my colonial complexes in the former colonizer’s land (I’m from India), pondering over my relationship, or the ruptures therein, with the former capital of imperialism but also with the Union Jack, the symbolism extended – as I watch over my chicken tikka heating up in the pan. Point of note: chicken tikka is the de facto national British dish. Not only that, the Scottish claim it as their 19-th century culinary invention.

Interesting perspective. Glad you seem to be delving deep into your experience in London.

Would have been interested in also hearing how studying abroad is specifically for a student of color; sounds from your introduction as though only white, upper middle class Americans are considered to be among the student body of the Butler exchange.